By tinkering with fine details within wood, engineers in Sweden have come up with an interesting new way of harvesting electricity. The technology leverages natural processes that already take place in drying wood, but supercharges it to capture enough electricity to run LEDs and other small devices.

Carried out by nanoengineers as KTH Royal Institute of Technology, the research centers on the sequence of events that play out when wood becomes wet and then dries. Called transpiration, this takes place in all plants as water moves through it and then evaporates, and actually produces tiny amounts of biolectricity.

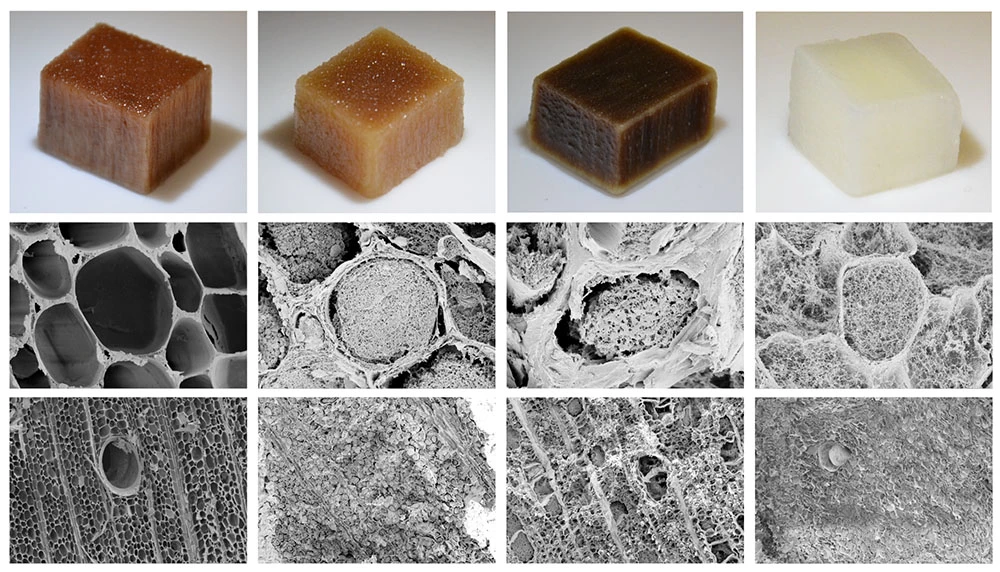

Previous efforts to capture and use this electricity have been hindered by low power density, but the authors believe they’ve solved this by re-engineering the wood cell walls. With a novel treatment involving sodium hydroxide, the team was able to create highly-porous versions with greater surface areas and greater cell wall permeability of water.

This results in a greater surface charge and water transportation through the material, which improves its ability to generate electricity. This was able to be boosted further by fine tuning of the wood’s pH levels.

"We compared the porous structure in regular wood with the material we improved with regard to surface, porosity, surface charge and water transportation,” said Yuanyuan Li. “Our measurements showed electricity generation that’s 10 times higher than with natural wood.”

In its current form, the engineered wood can deliver 1 volt and a power output of 1.35 microwatts per square centimeter. It is able to operate at this level for two to three hours and endure 10 water cycles before performance begins to drop off. More work is needed for the technology to really find practical use, but the scientists are excited by its potential.

"At the moment we can run small devices such as an LED lamp or a calculator,” Li says. “If we wanted to power a laptop, we would need about one square meter of wood about one centimeter thick, and about 2 liters of water. For a normal household we’d need far more material and water than that, so more research is needed."

The research was published in the journal Advanced Functional Materials.