The old saying “like water off a duck’s back” is well-earned – the water-loving birds have specialized feathers that keep them from getting too wet. Now, engineers at Virginia Tech have investigated the physics behind how they work and developed synthetic feathers that could help ships glide through the water more easily.

Duck feathers get their water-repelling abilities from a few features working in tandem. For one, ducks will regularly spread oil from a special gland over their outer feathers, which makes water form droplets and roll right off. But the microscale structure of the feathers also plays a key role, trapping air that keeps water away from the bird’s skin.

The Virginia Tech researchers first investigated what happens when multiple layers of these feathers are stacked up. They partly sealed a series of feathers and piled them on top of each other so that the unsealed sections lined up. This was placed in a pressure chamber, then water was poured onto the top feather, and air was piped in to force the water down through the feathers.

The team found that, understandably, the more feather layers there are, the more pressure is required to get the water through them all. And sure enough, it seems that different duck species will tend to have just the right amount of feather layers to keep them dry based on how deep they usually dive.

“Our hypothesis was to use multiple layers of feathers so that the water only comes in part way, but there are air pockets under that,” says Jonathan Boreyko, corresponding author of the study. “As long as those air pockets are present, it prevents something called irreversible wetting. As long as the wetting is only partial, they can shake it out when they surface.”

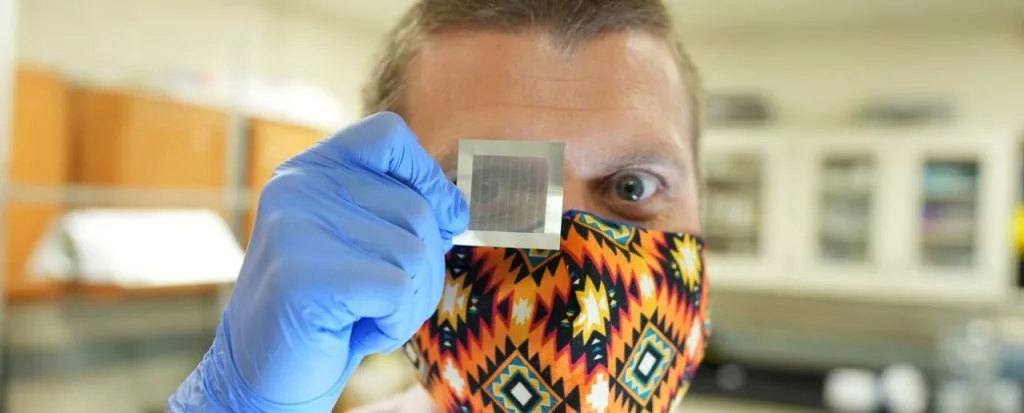

Based on what they’d learned from nature, the researchers then set about designing their own synthetic water-resistant feathers. They started with a thin sheet of aluminum foil, then laser cut series of slots just one tenth of a millimeter wide into it, then they etched a nanostructure into it that resembled tiny hairs. The result is a high surface area that traps air pockets more easily.

When they ran the tests again, the researchers found that their synthetic versions worked just as well as their natural inspiration. The team says this technique could eventually find use in making synthetic feathers for ships, to help reduce drag and stop barnacles from clinging on.

“If we think of a ship moving over the water as an engineered bird, right now it’s swimming naked,” says Boreyko. “We wonder if clothing the ship in feathers could impart the same enhancements that waterfowl benefit from.”

The research was published in the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Source: Virginia Tech