Whether a medication is taken orally or intravenously, it ends up traveling throughout the body instead of going solely to the one place where it's needed. Such could soon no longer be the case, however, thanks to a newly developed microparticle that looks like a flower.

Over the past several years we've seen multiple types of particles designed for targeted drug delivery.

In pretty much all cases, the microscopic objects are designed to be loaded up with a given medication, injected into the bloodstream, then externally steered to the site within the body where the drug is required. The particles can then be externally triggered to release their pharmaceutical payload, or simply left in place to diffuse it as they harmlessly dissolve.

Not only would such technology ensure that affected areas got sufficiently medicated, it would also drastically reduce side effects. After all, because none of the medication would be wasted by going where it wasn't needed, a much lower dosage would be required.

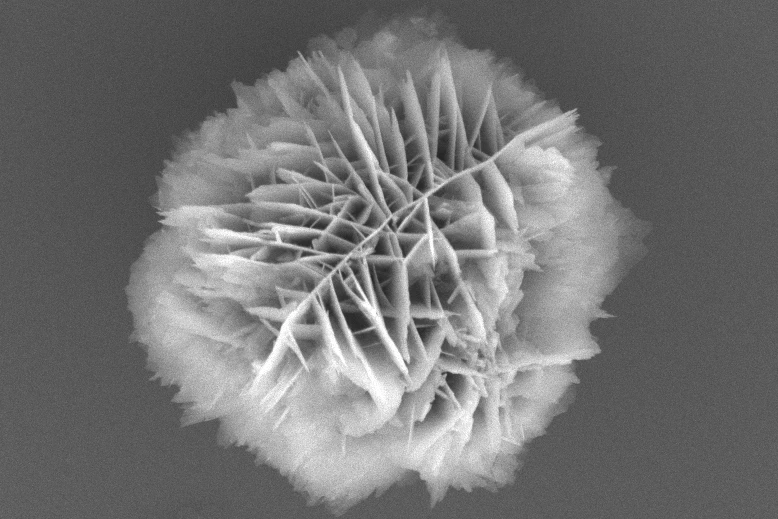

The new microparticles were developed by a team led by ETH Zurich's professors Daniel Razansky and Metin Sitti. Unlike most other drug-delivery particles, which take the form of smooth spheres, these ones look like tiny flowers made up of multiple petals.

Those petals are actually nanosheets of material which self-assemble into a three-dimensional cluster. Various materials can be used depending on the intended treatment, although the particles which were most closely analyzed in the study were made of zinc oxide. Others were made of polyimide, and a nickel/organic composite.

The flower-petal design offers two main advantages over spheres, which are typically either coated with medication or carry it in a minuscule internal reservoir.

First of all, it provides much more surface area for drug molecules to cling to, allowing each particle to carry a larger dose of medication. Secondly, the petals excel at scattering sound waves, making the particles easier to image via ultrasound (they can also be coated with light-absorbing molecules, boosting their visibility via optoacoustic imaging).

Not only can ultrasound be used to track the microparticles' location in the body, focused pulses of it can additionally be utilized to steer the particles through the bloodstream. In lab tests, focused ultrasound was successfully used to keep the particles "parked" in a specific location in the circulatory systems of mice, even as blood was flowing around the particles.

The scientists now plan on performing more animal tests, after which the technology may be made available for use in human patients with cardiovascular disease or cancer.

A paper on the research was recently published in the journal Advanced Materials.

Source: ETH Zurich