Researchers have developed an AI model that can predict in real-time whether a surgeon has removed all cancerous tissue during breast cancer surgery by examining a mammogram of the removed tissue. The model performed as well as, or better than, human doctors.

The preferred approach for early-stage breast cancer is breast-conserving surgery, otherwise known as a partial mastectomy, combined with radiotherapy. It’s vital that all cancerous breast tissue is removed during surgery to prevent the cancer from recurring. This is checked by examining the outer edges of the removed tissue to ensure they don’t contain cancer cells, known as ‘negative margins.’

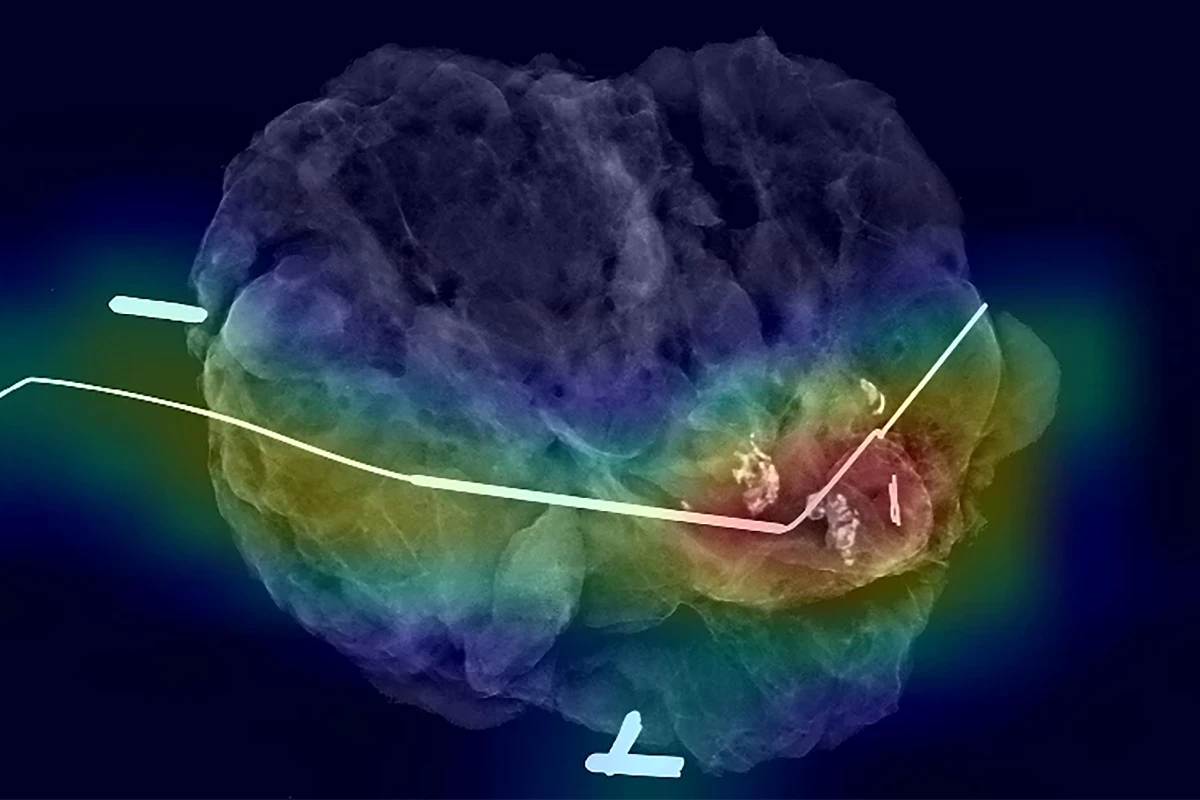

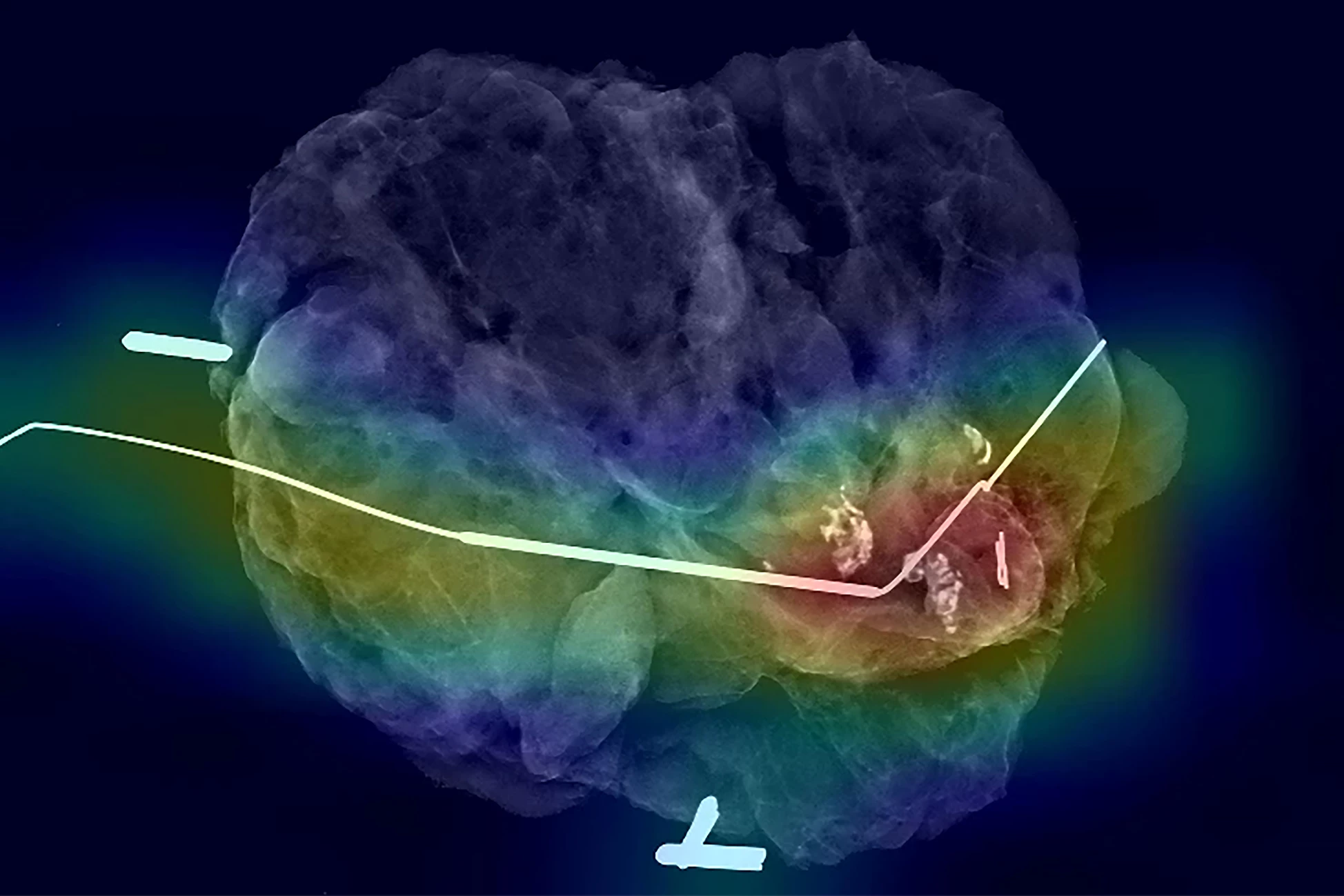

Mammography of the tissue (specimen mammography) is widely used as a means of ensuring negative margins, as it can be done in the operating room and provides immediate feedback. However, specimen mammography can be inaccurate, and if cancer cells are detected later, further surgery is required to remove additional tissue.

Researchers at the University of North Carolina (UNC) School of Medicine developed an AI model that can predict in real-time whether or not cancerous tissue has been fully removed during breast cancer surgery.

“Some cancer you feel and see, but we can’t see microscopic cancer cells that may be present at the edge of the tissue removed,” said Kristalyn Gallagher, one of the study’s corresponding authors. “Other cancers are completely microscopic. This AI tool would allow us to more accurately analyze tumors removed surgically in real-time and increase the chance that all of the cancer cells are removed during the surgery. This would prevent the need to bring patients back for a second or third surgery.”

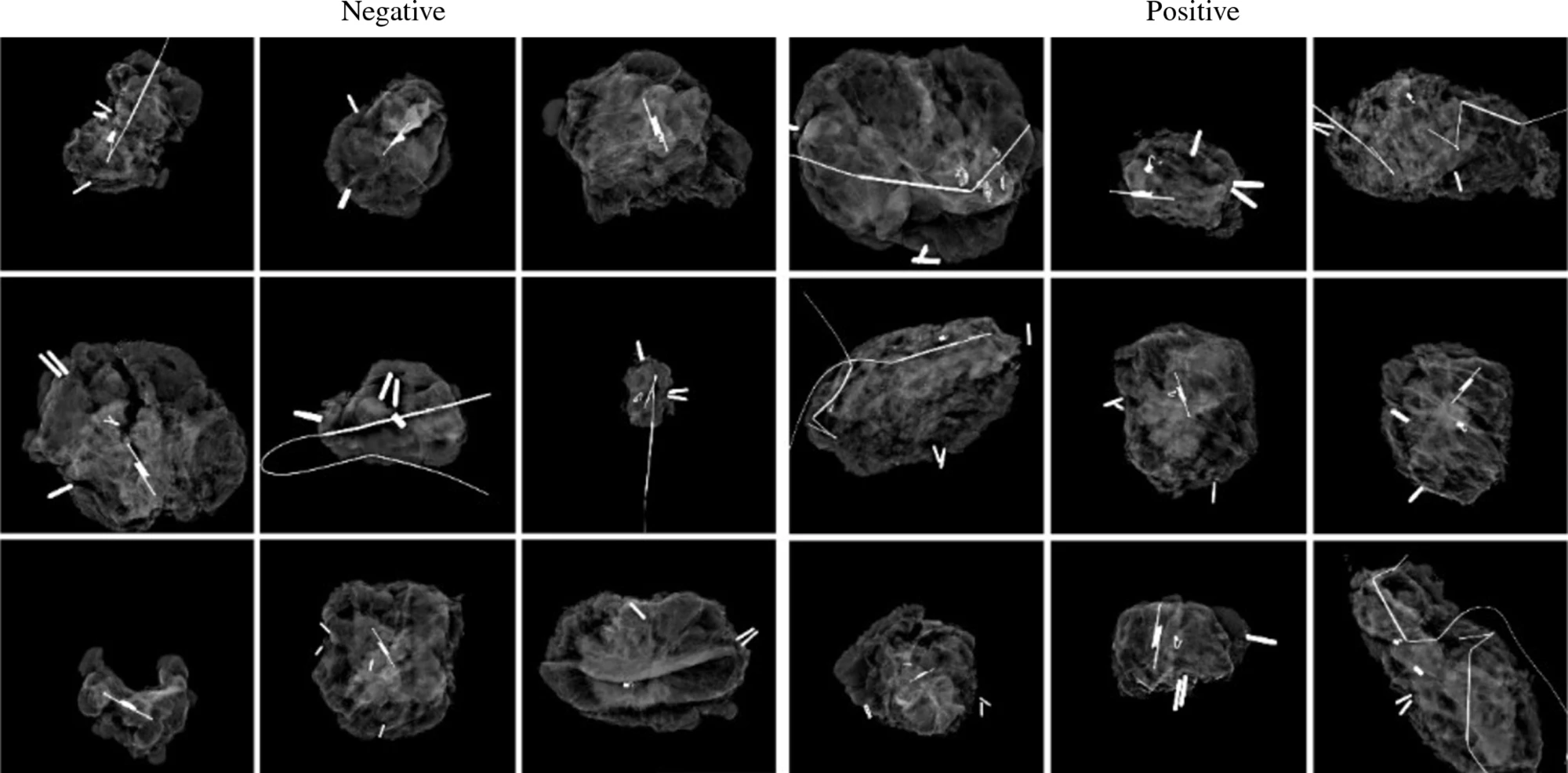

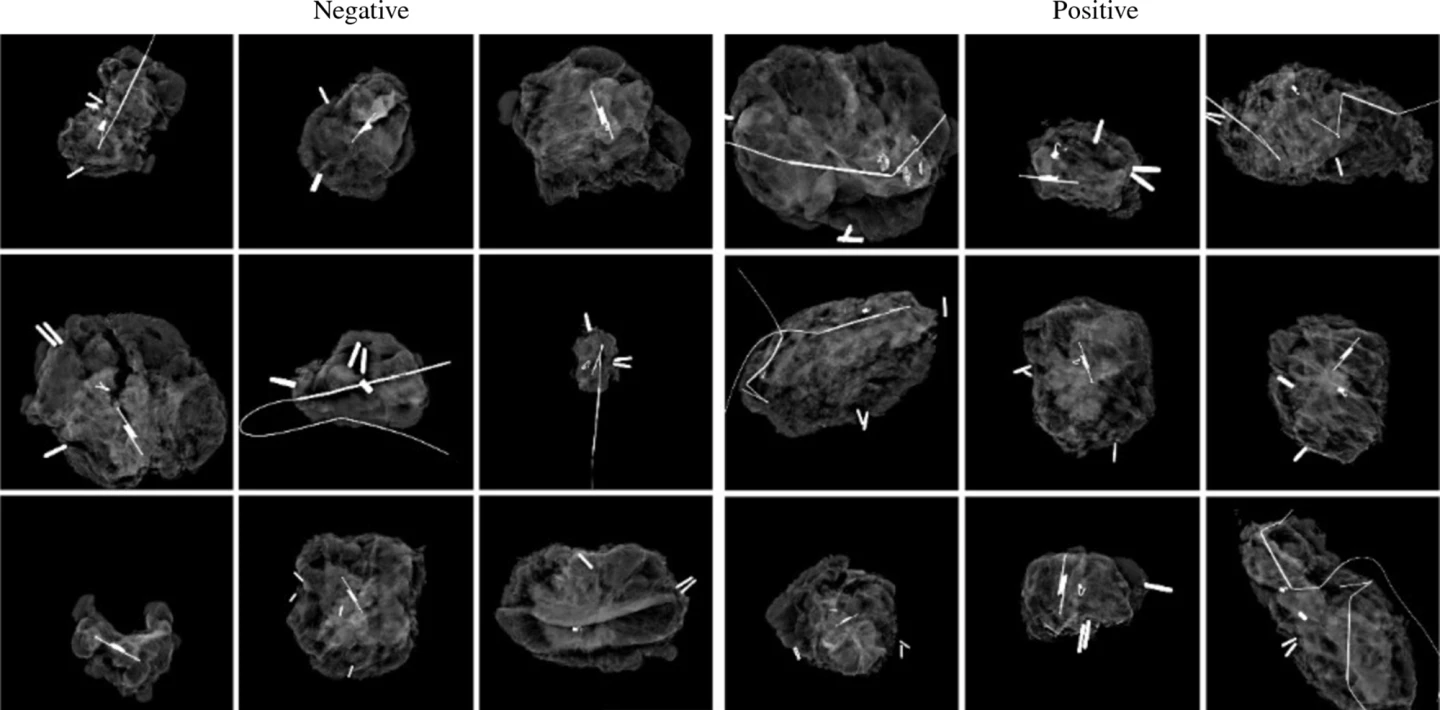

To ‘teach’ their AI model what negative and positive margins look like, the researchers used 821 specimen mammography images taken immediately after resection, matched with the final specimen reports from pathologists. Just over half (53%) of the images had positive margins. They also provided the model with demographic data from patients, such as their age, race, tumor type and tumor size.

They found that the AI model showed a sensitivity of 85%, a specificity of 45% and an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.71. Sensitivity is a measure of how well a model can detect positive instances, while specificity measures the proportion of true negatives that the model correctly identifies. AUROC measures the overall performance of a model, providing a value between zero and one, where 0.5 indicates random guessing, and one indicates perfect performance.

The researchers say that, compared to the accuracy of human interpretation, the AI model performed as well as, if not better than, humans. To put it in perspective, previous studies have found that specimen mammography has a sensitivity ranging from 20% to 58% and an AUROC ranging from 0.60 to 0.73.

“It is interesting to think about how AI models can support doctor’s and surgeon’s decision-making in the operating room using computer vision,” said Kevin Chen, the study’s lead author. “We found that the AI model matched or slightly surpassed humans in identifying positive margins.”

The model was helpful in discerning margins in patients with higher breast density. On mammograms, higher-density breast tissue and tumors both appear as bright white, making it difficult to tell healthy from cancerous tissue.

The researchers say their AI model could be used in hospitals with fewer resources, such as specialist surgeons, radiologists, or pathologists on hand to make quick, informed decisions in the operating room.

“It is like putting an extra layer of support in hospitals that maybe wouldn’t have that expertise readily available,” said Shawn Gomez, co-corresponding author. “Instead of having to make a best guess, surgeons could have the support of a model trained on hundreds or thousands of images and get immediate feedback on their surgery to make a more informed decision.”

The AI model is in its early stages, and the researchers will continue to teach it with more mammography images to improve its accuracy in discerning margins. Before it can be used in the clinical setting, the model will need to be validated in further studies.

The study was published in the journal Annals of Surgical Oncology.

Source: UNC Health