When someone has suffered a major nerve injury, there are two common treatments: performing a nerve graft, or utilizing a conduit to guide the regrowth of the injured nerve. While both approaches have their drawbacks, a new variation on the latter may succeed where they fail.

First of all, severed nerves are able to grow back together on their own. This is usually only the case if the gap between the two ends is no more than about a third of an inch, however. Any longer, and the regrowing nerve essentially misses its target, sometimes instead forming into a painful nerve-tissue ball known as a neuroma.

Therefore, for bridging larger gaps in places such as the arms, doctors usually perform a nerve graft. This most often involves harvesting a long, skinny sensory nerve from the back of the patient's leg; cutting that nerve into three pieces; bundling those pieces together laterally, in order to form one thicker length of nerve material; and then sewing that bundle onto the ends of the damaged nerve.

Unfortunately, doing so causes permanent numbness in the donor leg. Additionally, if the procedure is being used to repair a motor nerve, only about 40 to 60 percent of the original motor function typically returns.

Another option involves implanting a small conduit tube at the injury site. This guides the nerve as it regrows, ensuring that its two ends meet back up. According to scientists at the University of Pittsburgh, though, there are currently no commercially-available conduits that are FDA-approved for the bridging of gaps longer than one inch.

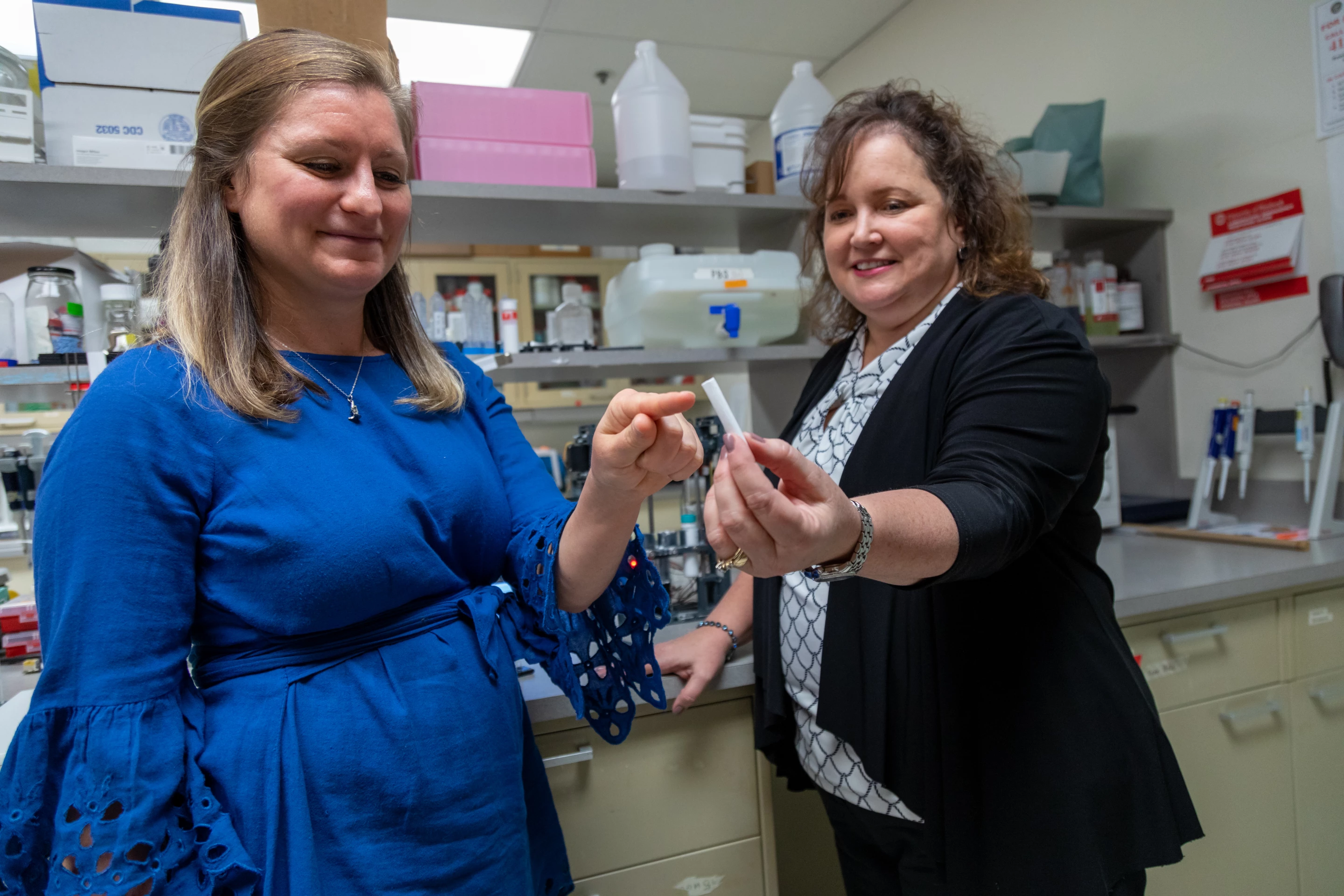

With that limitation in mind, those researchers have designed what they say is a better-performing tube. It's made from the same biodegradable polyester as dissolvable sutures, and is lined with microspheres of a growth-promoting protein called GDNF (glial-cell-derived neurotrophic factor). That protein is slowly released over the treatment period, continuously promoting nerve growth. No stem cells, which have been used in some other experimental conduits, are required.

The device was tested on macaque monkeys, each of which had a 2-inch (51-mm) gap between the severed end of one of their forearm motor nerves and its associated muscle.

One group of the primates was treated using the new conduits, a second group was treated with empty polymer tubes, and a third group received nerve grafts. In the case of the latter, because monkeys' legs are too short for traditional nerve-harvesting, a section of nerve was simply extracted from their forearm, flipped around, and then sewn back in place. Because those grafts were made of the exact same material as the injured nerve, this scenario was expected to restore more function than traditional leg-to-arm grafts.

After a one-year recovery period, it was found that the Pittsburgh conduits outperformed the empty tubes, restoring about 80 percent of fine motor control to the thumbs of four of the monkeys. As compared to the grafts, the conduits restored approximately the same amount of functionality. That said, they did better at triggering the replenishment of Schwann cells – these form an insulating layer around nerves, which both boosts the transmission of electrical signals and aids in nerve regeneration.

The scientists are now commercializing the technology via spinoff company AxoMax Technologies, and hope to begin human clinical trials soon. In the meantime, a paywalled paper on the research can be found in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"We're the first to show a nerve guide without any cells was able to bridge a large, 2-inch gap between the nerve stump and its target muscle," says Prof. Kacey Marra, who led the study alongside Lauren Kokai and Neil Fadia. "Our guide was comparable to, and in some ways better than, a nerve graft."

Sources: University of Pittsburgh, American Association for the Advancement of Science via EurekAlert