When a patient receives an organ transplant, they have to take drugs in order to keep their immune system from rejecting the organ – and those drugs often have serious side effects. Such medication may one day no longer be necessary, however, thanks to a new blood vessel coating.

Ordinarily, the inner walls of blood vessels within organs are naturally coated with special sugars that suppress the body's immune response.

When organs are harvested and stored for transplantation, however, the sugars are damaged and become ineffective. As a result, once such an organ is transplanted, the recipient's immune system sees it as an unwelcome foreign object. The patient's white blood cells then proceed to attack the organ, through the walls of its blood vessels.

Led by Dr. Jayachandran Kizhakkedathu, scientists at Canada's University of British Columbia have now developed a biocompatible polymer that can be applied to the arteries, veins and capillaries of harvested organs, serving the same protective role as the compromised sugars.

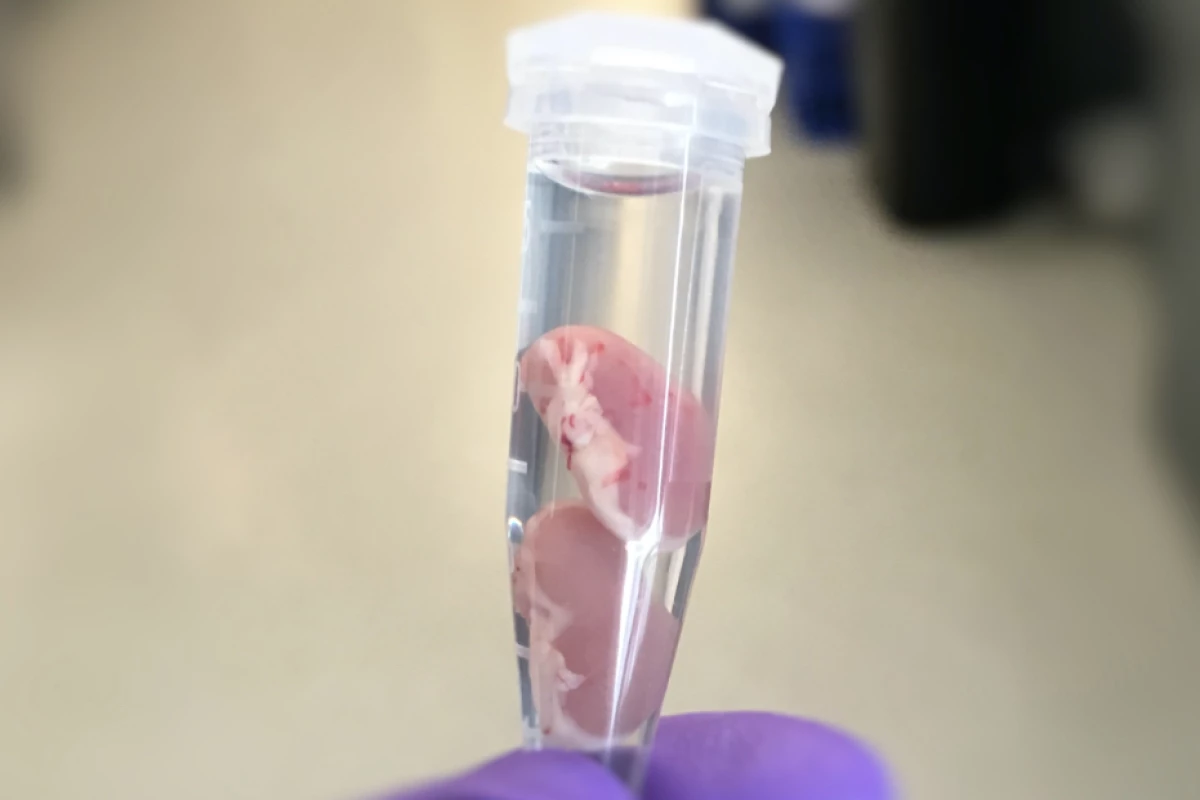

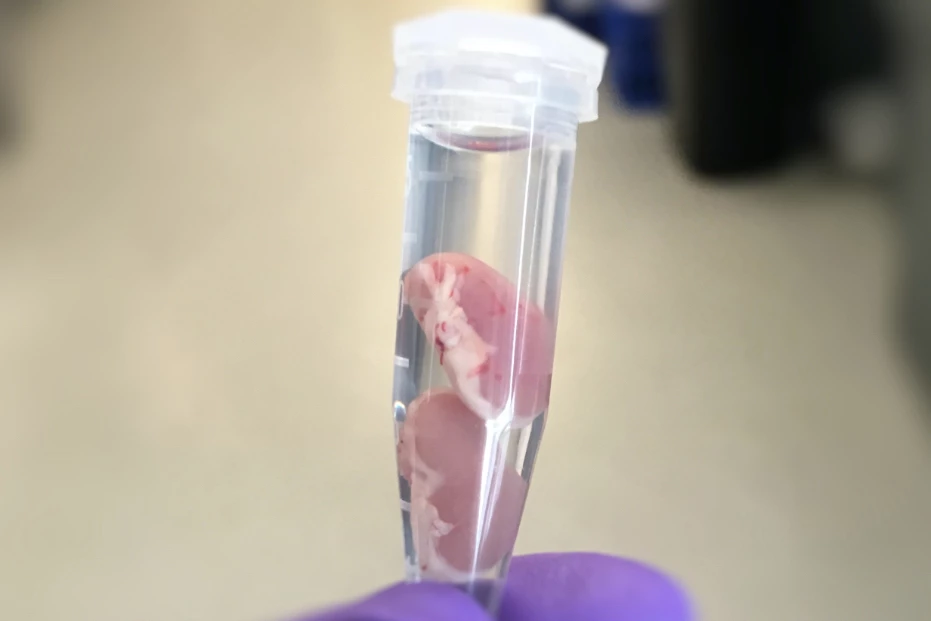

In lab tests performed at Vancouver's Simon Fraser University, it was determined that after being coated with the polymer and then transplanted, a mouse artery "would exhibit strong, long-term resistance to inflammation and rejection." Additional experiments performed at Illinois' Northwestern University showed that the coating prevented rejection of kidneys transplanted between mice.

Kizhakkedathu tells us that the coating does eventually dissolve, once the crucial introduction period of the organ has passed. And while it may still be several years before clinical trials on humans begin, it is believed that the technology could ultimately make a huge difference in patients' lives.

"We’re hopeful that this breakthrough will one day improve quality of life for transplant patients and improve the lifespan of transplanted organs," says Kizhakkedathu.

A paper on the research – which also involved Dr. Stephen Withers, PhD candidate Daniel Lo and Dr. Erika Siren – was recently published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Source: University of British Columbia