Traumatic brain injuries can have severe and long-lasting repercussions that involve damage to the organ's tissue, cognitive impairments and disability. An implantable "brain glue" material developed at the University of Georgia could offer a way to intervene, by mimicking the supporting structure of brain cells to prevent tissue loss and regenerate neurons.

The "brain glue" is a type of hydrogel that was actually created back in 2017 by the University of Georgia 's Lohitash Karumbaiah. The material is designed to replicate the meshwork of sugars that support brain cells, by incorporating key structures that bind to basic fibroblast growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, protective proteins that boost survival and regrowth of brain cells after injury.

Previously, Karumbaiah and his colleagues had shown that this hydrogel could be injected into rats with traumatic brain injury to protect them against the tissue loss that would normally result, with observations four weeks later showing a significantly enhanced retention of neural stem cells.

The team has since made refinements to the hydrogel by re-engineering the surfaces of the protective proteins to promote regeneration of brain cells and restoration of their function. The improved hydrogel was again implanted into rats with severe traumatic brain injury, who after 20 weeks exhibited enhanced cell repair and improvement of motor function.

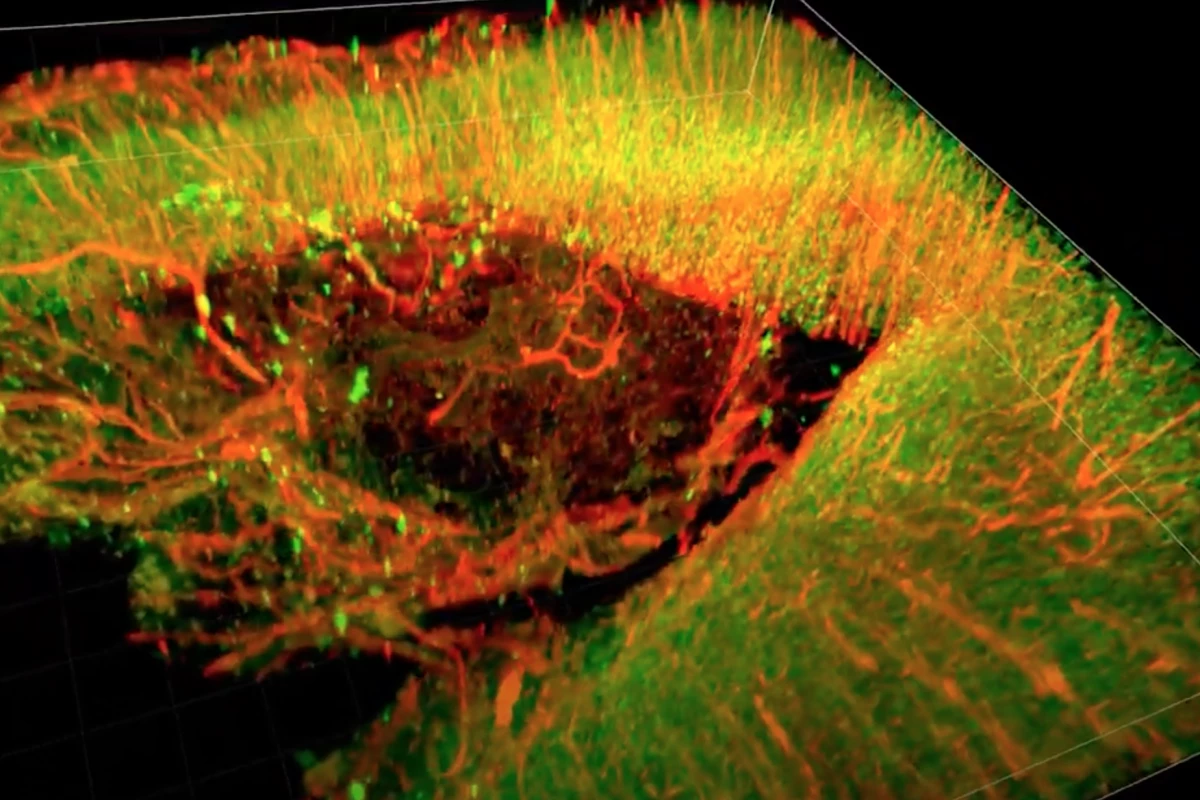

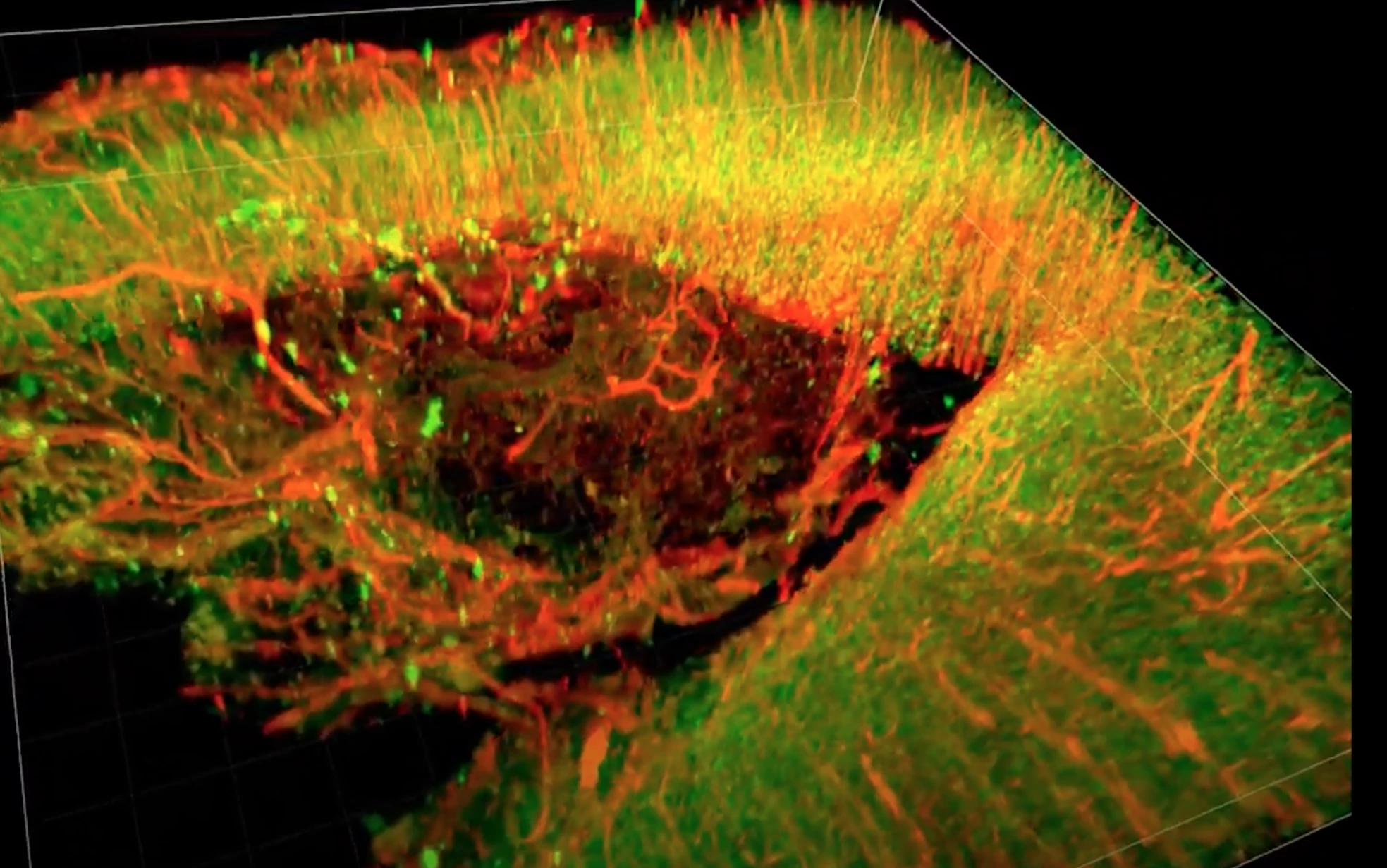

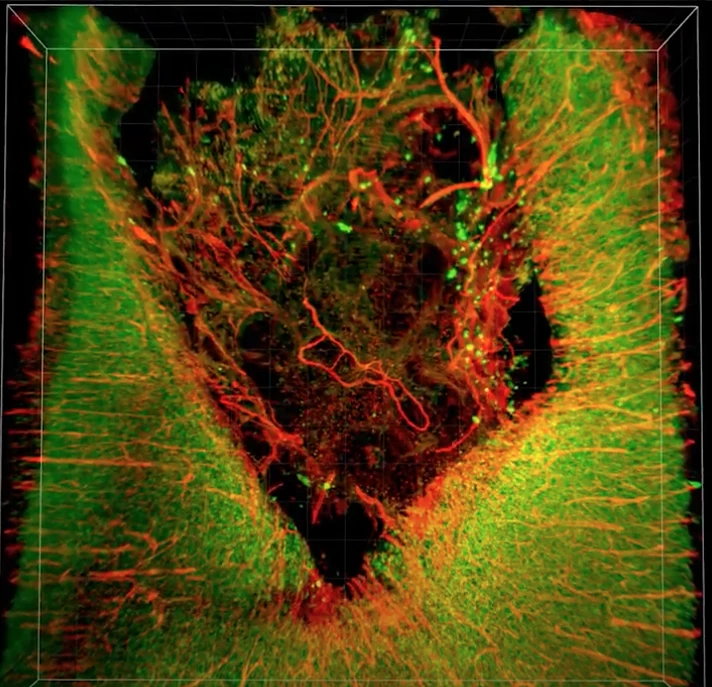

This was observed through 3D imaging technique known as tissue-clearing, to show the rodent's brains during "reach-to-grasp" movements. This showed that the brain glue not only protected against tissue loss, but actively regenerated functional neurons at the site of the injury.

“Because of the tissue-clearing method, we were able to obtain a deeper view of the complex circuitry and recovery supported by brain glue,” says Karumbaiah. “Using these methods along with conventional electrophysiological recordings, we were able to validate that brain glue supported the regeneration of functional neurons in the lesion cavity.”

Conveniently, the neural circuit involved in reach-to-grasp motion in rats is similar to the one in humans, which the scientists say could help speed up the progress toward clinical use for the brain glue.

The research was published in the journal Science Advances, while the video below offers a look at the 3D images of the injured rat brains used as part of the study.

Source: University of Georgia