Nobody likes needles, but they’re often a necessary evil. Microneedle patches are emerging as a painless alternative, and now researchers at City University of Hong Kong have developed a new version of the tech that’s made of ice, for easier manufacture and use.

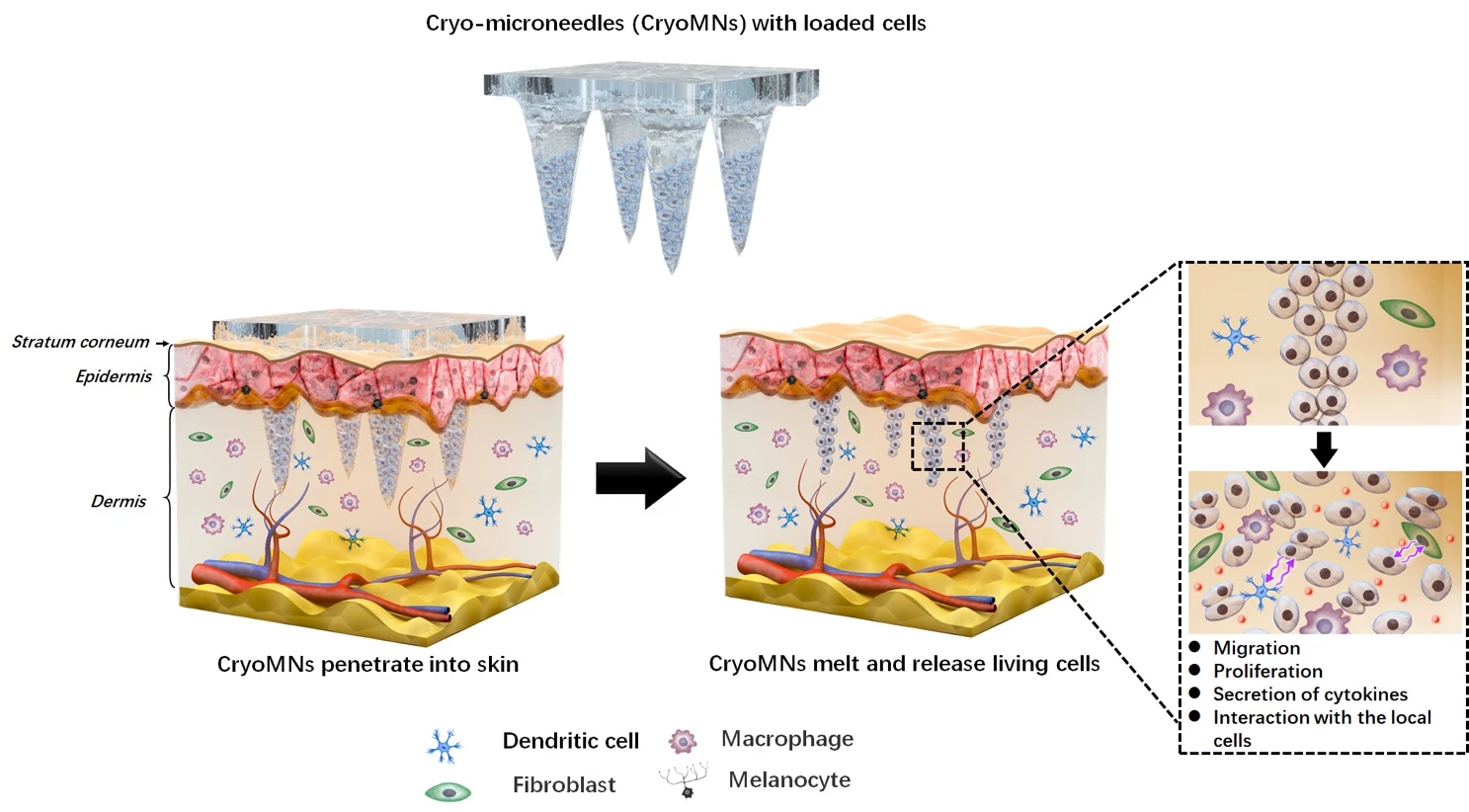

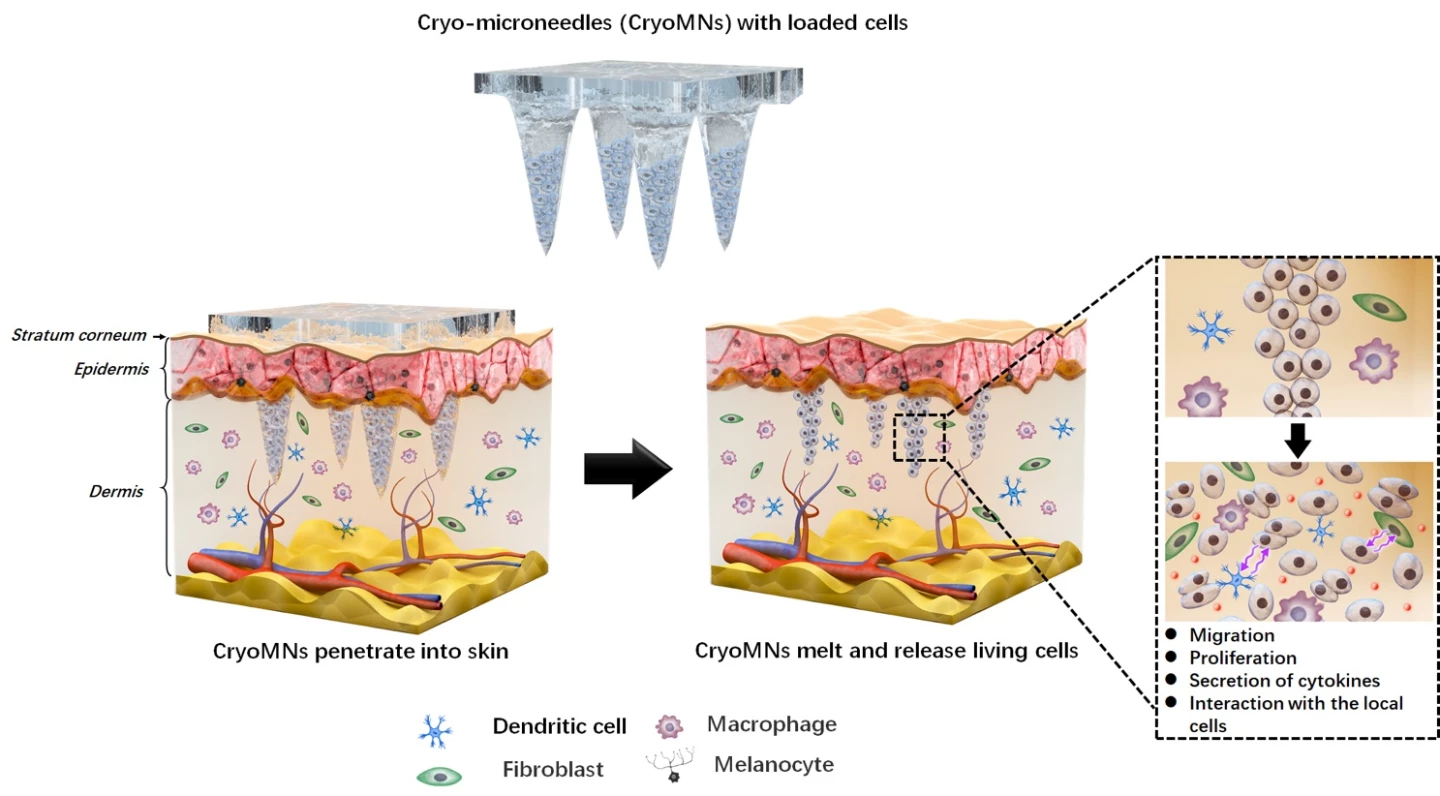

Microneedle patches are designed to be applied to the skin like a Band-Aid, with the skin-facing side containing an array of the tiny needles. Unlike the big hypodermic needles that need to be long enough to reach the vein in your arm, microneedles are less than 1 mm long. That means they only penetrate a very short distance into the skin, falling short of the nerve endings so they’re painless.

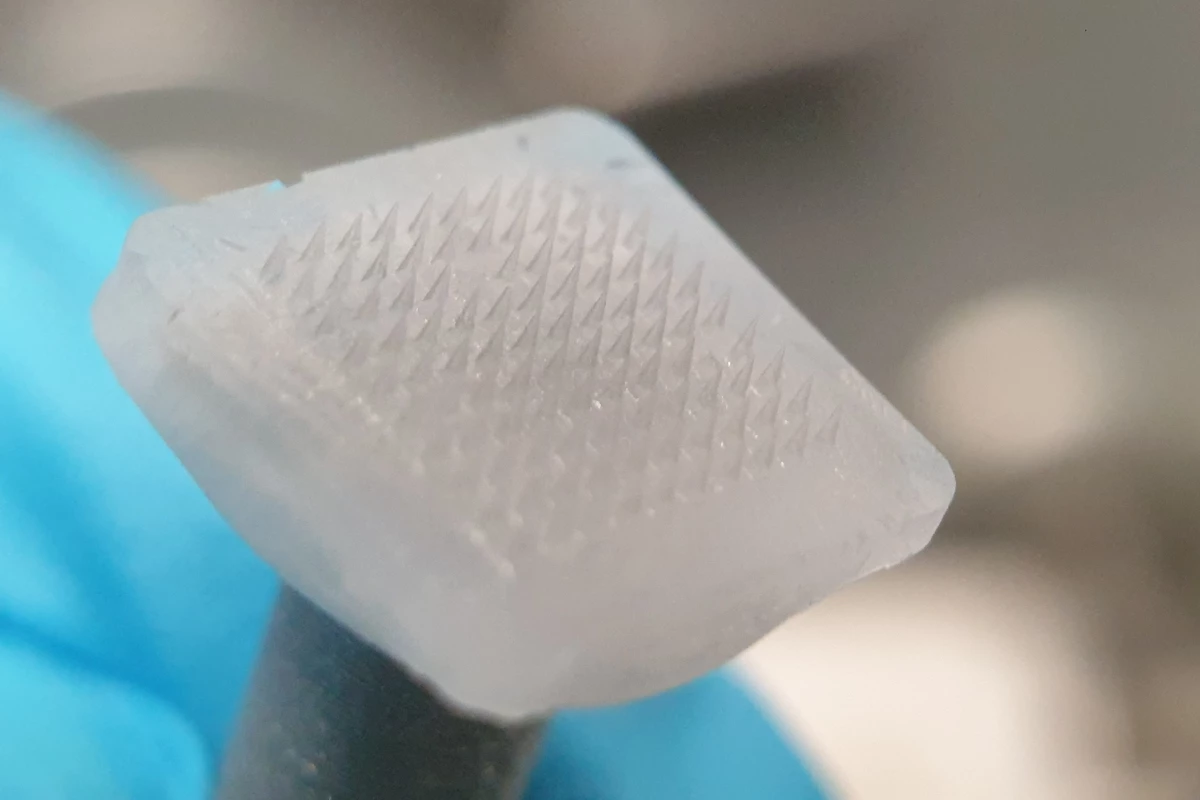

Usually, the needles themselves are made of biodegradable polymers that dissolve to release a payload, which can be drugs, vaccines, cells or other therapeutic molecules. But for the new study, the CityU researchers made theirs out of a simpler material – ice.

The principle for these cryomicroneedles is mostly the same. Therapeutic cells are loaded into the microneedles, although in this case they’re paired with a cryoprotectant then frozen in the ice. Once the needles enter the skin, they break off the backing patch and the patient’s body heat melts them, delivering their payload.

The team says that using ice has a few advantages over existing microneedle systems. The most obvious is that it’s a simpler material to make than biodegradable polymers, but they also leave less waste and the ice can also preserve the cells for long-term cold storage. That said, the requirement to remain frozen could be a downside for shipping and storage.

In tests, the researchers used the cryomicroneedles to treat cancer in mice. They loaded the patches with ovalbumin-pulsed dendritic cells – a form of cancer immunotherapy – and found that the immune responses it triggered were better than those from subcutaneous or intravenous injection.

It’s an interesting twist on the idea, but whether it stacks up remains to be seen with further tests. The team notes that other payloads could be integrated into the devices too.

“The application of our device is not limited to the delivery of cells,” says Dr. Xu Chenjie, lead author of the study. “This device can also package, store, and deliver other types of bioactive therapeutic agents, such as proteins, peptides, mRNA, DNA, and vaccines. I hope this device offers an easy-to-use and effective alternative method for the delivery of therapeutics in clinics.”

The research was published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Source: City University of Hong Kong