Researchers have developed an "inverse vaccine" that reverses the damage caused when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s healthy organs and tissues in autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis. It could pave the way to a treatment for these diseases that doesn’t require suppressing the entire immune system.

Normally, a vaccine teaches the body’s immune system to recognize a viral or bacterial invader as an enemy that needs to be destroyed. Now, researchers from the University of Chicago have created an “inverse vaccine” that does the opposite.

The novel vaccine removes the immune system’s memory of one molecule, which, when fighting pathogens, would be undesirable but, in the context of autoimmune diseases, may prove to be a cure.

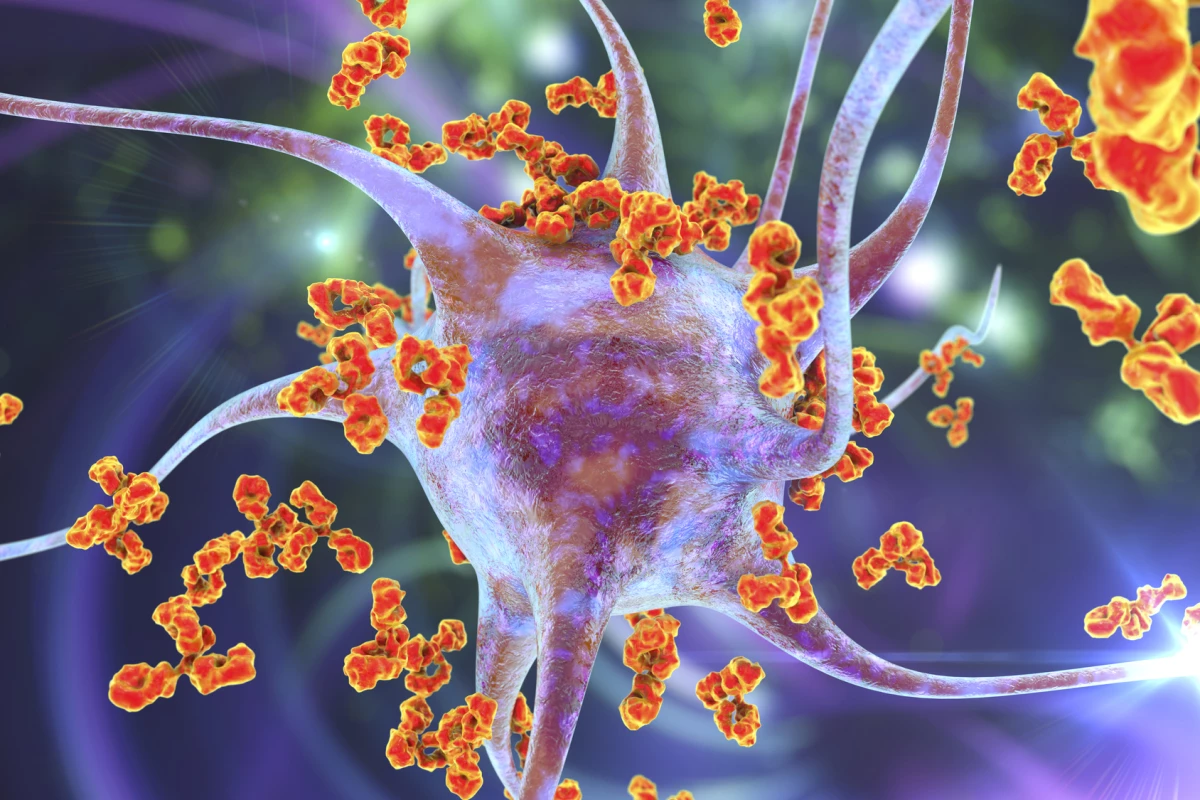

It’s the job of the immune system’s T cells to recognize specific foreign antigens on the surfaces of unwanted cells and launch an attack against them. However, T cells can sometimes get it wrong. In the case of autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS), type 1 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis, the T cells become self-reactive, mistakenly considering healthy organs and tissues to be foreign organisms.

The researchers were aware of the importance of the liver in mediating local and systemic tolerance to self-antigens and foreign antigens. They exploited the organ’s natural mechanism of marking molecules from broken down cells with a ‘do not attack’ flag to prevent autoimmune reactions to cells that die by natural processes. By coupling an antigen with a molecule resembling a fragment of an aged cell, the liver recognized it as a friend rather than an enemy.

“In the past, we showed that we could use this approach to prevent autoimmunity,” said Jeffrey Hubbell, a corresponding author of the study. “But what is so exciting about this work is that we have shown that we can treat diseases like multiple sclerosis after there is already ongoing inflammation, which is more useful in a real-world context.”

The liver’s role in ‘peripheral immune tolerance,’ a mechanism whereby self-reactive T cells are deleted or become anergic (functionally unresponsive to antigens), prevents the body from mounting an inappropriate immune response. In previous studies, the researchers had discovered that tagging molecules with a sugar known as N-acetylgalactosamine (pGal) mimicked this process, sending the molecules to the liver where tolerance to them developed.

“The idea is that we can attach any molecule we want to pGal, and it will teach the immune system to tolerate it,” said Hubbell. “Rather than rev up immunity as with a vaccine, we tamp it down in a very specific way with an inverse vaccine.”

In the current study, the researchers focused on a mouse model with MS-like disease, in which the immune system attacks myelin, the insulating sheath around nerves. They linked myelin proteins to pGal and tested the effect of the inverse vaccine and found the immune system stopped attacking myelin, allowing the nerves to function properly and reversing the symptoms of disease.

Currently, autoimmune diseases are generally treated with immunosuppressant drugs that inhibit the entire immune system, which is not ideal.

“These treatments can be very effective, but you’re also blocking the immune responses necessary to fight off infections, and so there are a lot of side effects,” Hubbell said. “If we could treat patients with an inverse vaccine instead, it could be much more specific and lead to fewer side effects.”

Phase 1 clinical trials are underway to evaluate the safety of the treatment in people with multiple sclerosis.

“There are no clinically approved inverse vaccines yet, but we’re incredibly excited about moving this technology forward,” said Hubbell.

The study was published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Source: University of Chicago