Inspired by the bacteria-killing structures seen on the wings of some insects, researchers have developed a drug-free way to kill off drug-resistant microbes that commonly cause hospital-acquired infections. Their technique is a novel and effective way of tackling the problem of antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

Surgery can lead to infection, and, with the rise in drug-resistant microbes, providing effective treatment is becoming mor difficult. While bacteria are usually the main infection-causing culprits, drug-resistant species of Candida, a type of fungus, are also proving problematic. Not only can they effectively colonize and form biofilms on implanted materials, leading to hospital-acquired infections, but they also lead to poor clinical outcomes.

When they’re inserting things like titanium hips or dental prostheses, doctors use a range of antimicrobial coatings, chemicals and antibiotics to prevent infection from developing. But these measures won’t be as effective, or effective at all, if the microbe in question has developed resistance.

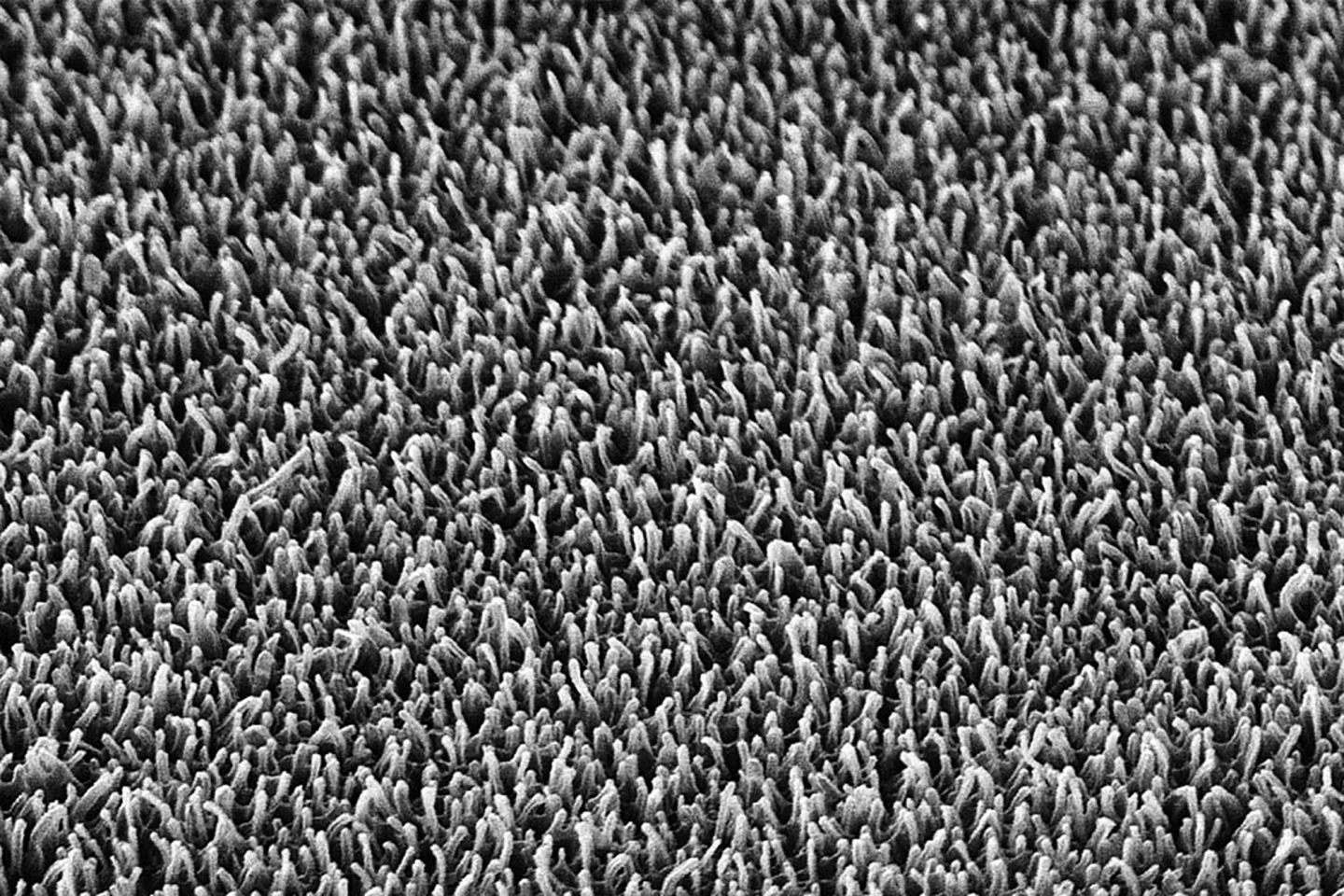

But, researchers from RMIT University have come up with a novel, drug-free way to kill superbugs that’s inspired by the antimicrobial surface on the wings of some insects. Insects such as dragonflies, cicadas, and damselflies have tiny pillars – nanopillars – on the surface of their wings that act as a “mechano-biocidal,” physically pulling apart bacterial cells and killing them.

“It’s like stretching a latex glove,” said Elena Ivanova, corresponding author of the study. “As it slowly stretches, the weakest point in the latex will become thinner and eventually tear.”

So, the researchers set about creating their own mechano-biocidal, developing a titanium surface covered with specially designed microscale spikes, each about the size of a bacteria cell, using a technique called plasma etching.

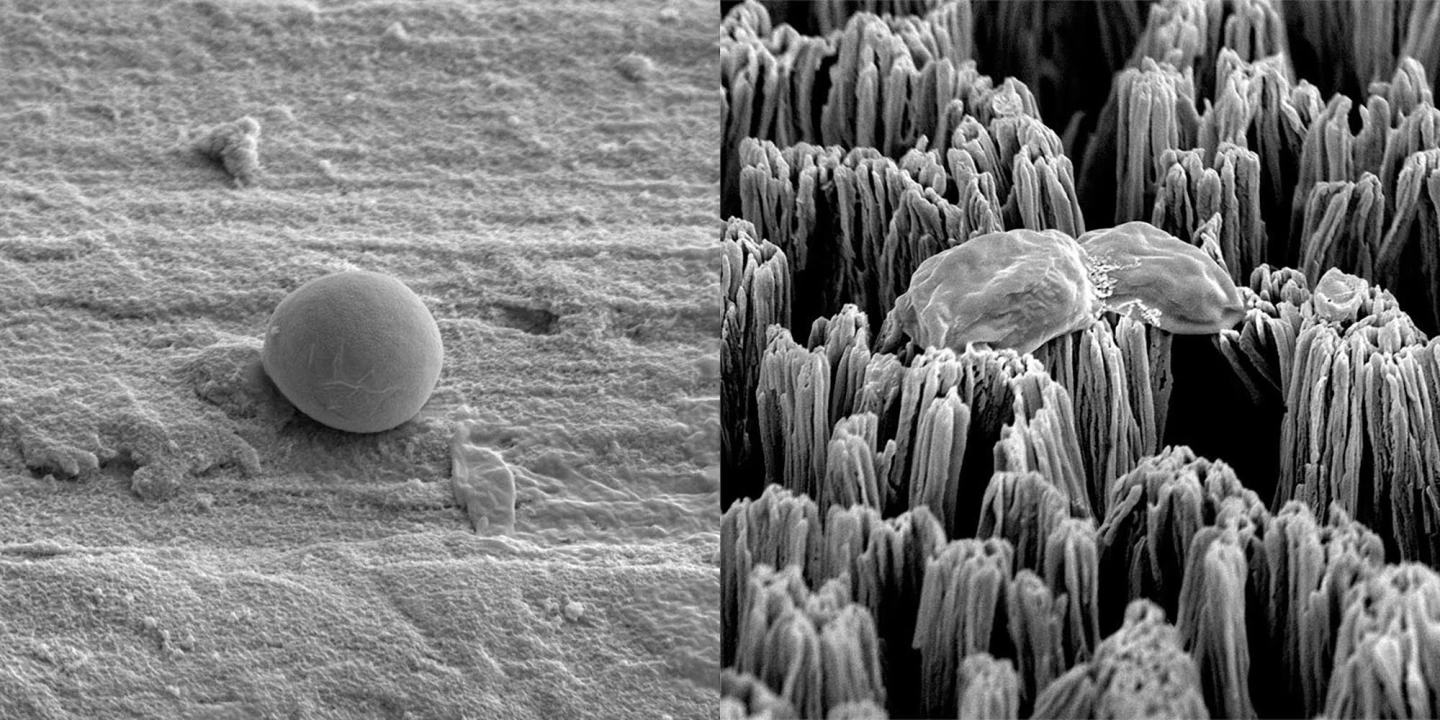

They tested the effectiveness of the surface in killing multi-drug-resistant Candida and found that about half the cells were destroyed soon after making contact with the spikes. Significantly, the other half – the cells that were not immediately destroyed – were injured enough that they were unable to reproduce or cause infection.

“The Candida cells that were injured underwent extensive metabolic stress, preventing the process where they reproduce to create a deadly fungal biofilm, even after seven days,” said Denver Linklater, one of the study’s co-authors. “They were unable to be revived in a non-stress environment and eventually shut down in a process known as apoptosis, or programmed cell death.”

The micropillared titanium surface had already been found to be effective against two common pathogens, Staphylococcus aureus (‘Golden Staph’) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria, in a previous study published in the journal Materialia.

“The fact that cells died after initial contact with the surface – some by being ruptured and others by programmed cell death soon after – suggests that resistance to these surfaces will not be developed,” Ivanovna said. “This is a significant finding and also suggests that the way we measure the effectiveness of antimicrobial surfaces may need to be rethought.”

The researchers say the relatively simple plasma etching technique they used to create the spikes could be applied across a wide range of materials and applications.

“This new surface modification technique could have potential applications in medical devices but could also be easily tweaked for dental applications or for other materials like stainless steel benches used in food preparation and agriculture,” said Ivanovna.

The study was published in the journal Advanced Materials Interfaces.

Source: RMIT University