Researchers have developed the world’s first oral drug to target a form of cholesterol that has previously been untreatable and is largely caused by genetics, making it difficult to control by way of exercise, diet or other lifestyle factors.

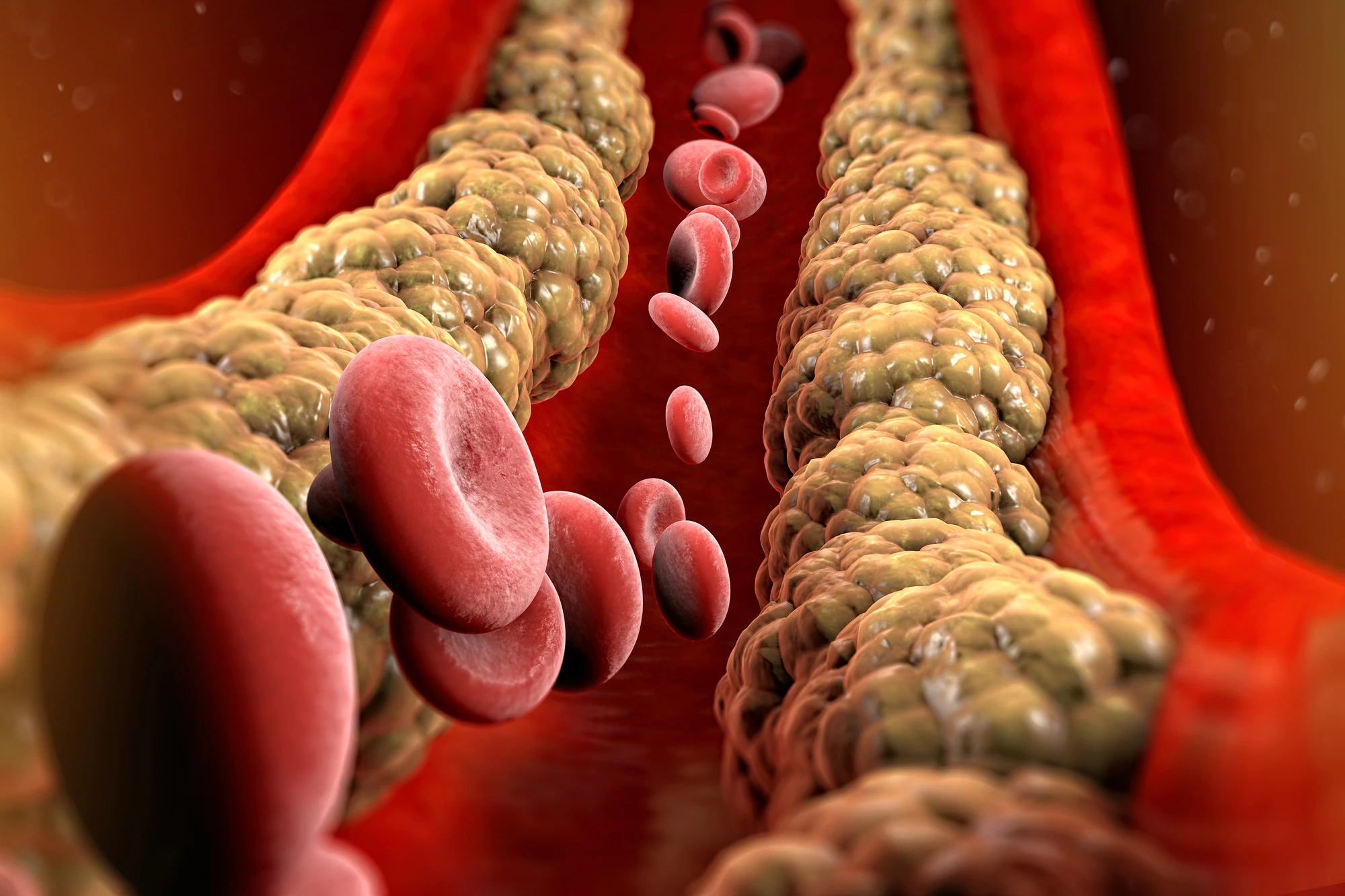

Studies have shown that high levels of lipoprotein(a) or Lp(a), pronounced “L-P-little-A”, increase the likelihood of heart attack or stroke, particularly with familial hypercholesterolemia, an inherited condition characterized by high cholesterol. Lp(a) is a type of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, otherwise known as ‘bad cholesterol,’ but it’s stickier, increasing the risk of blockages and blood clots (atherosclerosis) forming in the arteries.

Commonly used cholesterol-lowering drugs such as statins don’t have the same effect on Lp(a), and because it’s largely caused by genetics, Lp(a) is also difficult to control through diet, exercise and other lifestyle changes. There are no approved medications currently available that target Lp(a).

However, a team led by researchers at Monash University have developed and tested a groundbreaking, world-first oral medication, muvalaplin, that interrupts the body’s ability to form Lp(a).

“When it comes to treating high Lp(a), a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease, our clinicians currently have no effective tools in their kit,” says Stephen Nicholls, the study’s lead author. “Lp(a) is essentially a silent killer with no available treatment, this drug changes that.”

Lp(a) is composed of one molecule of an LDL-particle containing apolipoprotein B100 (apo B100) and one molecule of a glycoprotein called apolipoprotein(a), or apo(a). Mulvalaplin disrupts the interaction between apoB100 and apo(a), resulting in lower Lp(a) levels.

The trial enrolled a total of 114 participants; 89 were treated with muvalaplin, and 25 were given a placebo. The trial was conducted in two parts. The first part evaluated the effect of only one dose of muvalaplin in ascending increments, from 1 mg to 800 mg, in healthy participants with a mean age of 29. The second part evaluated the effect of a single daily dose in ascending increments (30 mg to 800 mg) taken over 14 days by healthy participants whose mean age was 32 and who had elevated Lp(a) plasma levels.

Baseline Lp(a) and LDL cholesterol levels were taken at the start of the trial and the effect of muvalaplin on Lp(a) levels observed. The researchers saw reduction in Lp(a) levels from baseline as early as day two with the participants receiving multiple doses. The reduction in Lp(a) was 64% to 65% at doses of 100 mg or more, occurring on days 14 and 15.

Of participants in the single ascending dose group, the most common adverse events were headache (33%), back pain (13%) and fatigue (11%). The multiple ascending dose group reported experiencing headache (31%), diarrhea (20%), abdominal pain (15%), nausea (10%) and fatigue (10%). No deaths or serious adverse events were reported.

The researchers note the study’s limitations, namely that it was a small, phase 1 study. Larger, longer clinical trials in more diverse populations, including those with established cardiovascular disease, will be needed to establish the safety profile of muvalaplin. Additionally, study participants had low-to-moderate elevation of Lp(a) levels; the drug’s target audience would likely include people with greater Lp(a) elevations.

Nonetheless, as the first oral agent specifically developed to lower Lp(a) levels, muvalaplin is a promising development.

“This drug is a game-changer in more ways than one,” Nicholls said. “Not only do we have an option for lowering an elusive form of cholesterol, but being able to deliver it in an oral tablet means it will be more accessible for patients.”

The study was published in the journal JAMA Network.

Source: Monash University