Ants have a reputation as the hard workers of the animal kingdom, in part because they can lug around impressively heavy loads with respect to their size. But tiny new robots being developed at Stanford University are giving them a run for their money with the ability to pull up to 1,800 times their own weight.

When it comes to finding new ways of getting around, robotics experts turn to nature for inspiration time and time again. Many robots walk like insects, some slither like snakes, others swim like jellyfish, and quite a few can fly like birds.

By making use of what's known as the van der Waals force, the same force used by ants to pull heavy loads and by geckos to climb on vertical glass walls, Stanford researchers have developed "MicroTugs" – tiny robots that, through use of a special directional adhesive, can pull nearly 2,000 times their own weight.

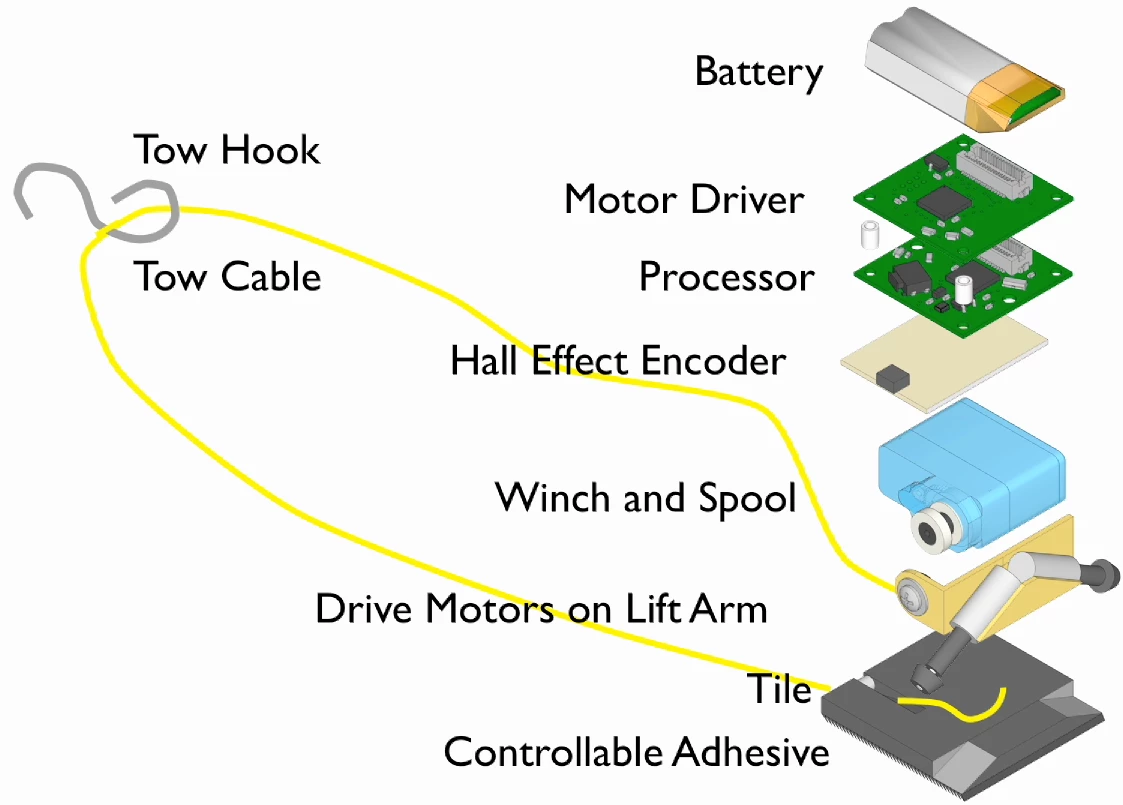

The robot's design incorporates a strong adhesive deposited onto a series of 100-micrometer flexible wedges made of silicone rubber. Under normal conditions, only the very tips of the wedges make contact with the surface underneath, meaning that the robot is essentially free to move without resistance. But the microrobots are also able to push the wedges down, which makes them stick firmly to the ground when needed.

To pull off their amazing feat, Stanford's tiny robots simply alternate between freely moving forward and pulling on a heavy weight while sticking firmly to the ground, using actuators that continuously and quickly switch between the two states.

The result is a 12 g (0.4 oz) robot able to tow weights up to 21 kg (46 lbs), or 1,800 times its body weight.

The Stanford researchers used the same principles to build several variations of their microrobots using different materials, from solid state actuators to shape memory alloys. A piezoelectric robot showed that the adhesive can be made to cycle quickly (up to 16 times a second) between its sticky and unsticky states, while other robots were able to pull impressive payloads vertically – a tiny 20-milligram robot, powered by an external heat source, was able to hoist a clipboard 25 times its own weight up a vertical wall.

The robots are set to be presented later this month at the International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA).

The potential applications for this technology for lifting heavy loads in factories or construction sites is clear – just check out the video below.

Source: Stanford University