University of Maryland engineers have created a new insulating material capable of blocking at least 10 degrees more heat than styrofoam or silica aerogel. It's also 30 times stronger than styrofoam, and appears to be much more environmentally friendly.

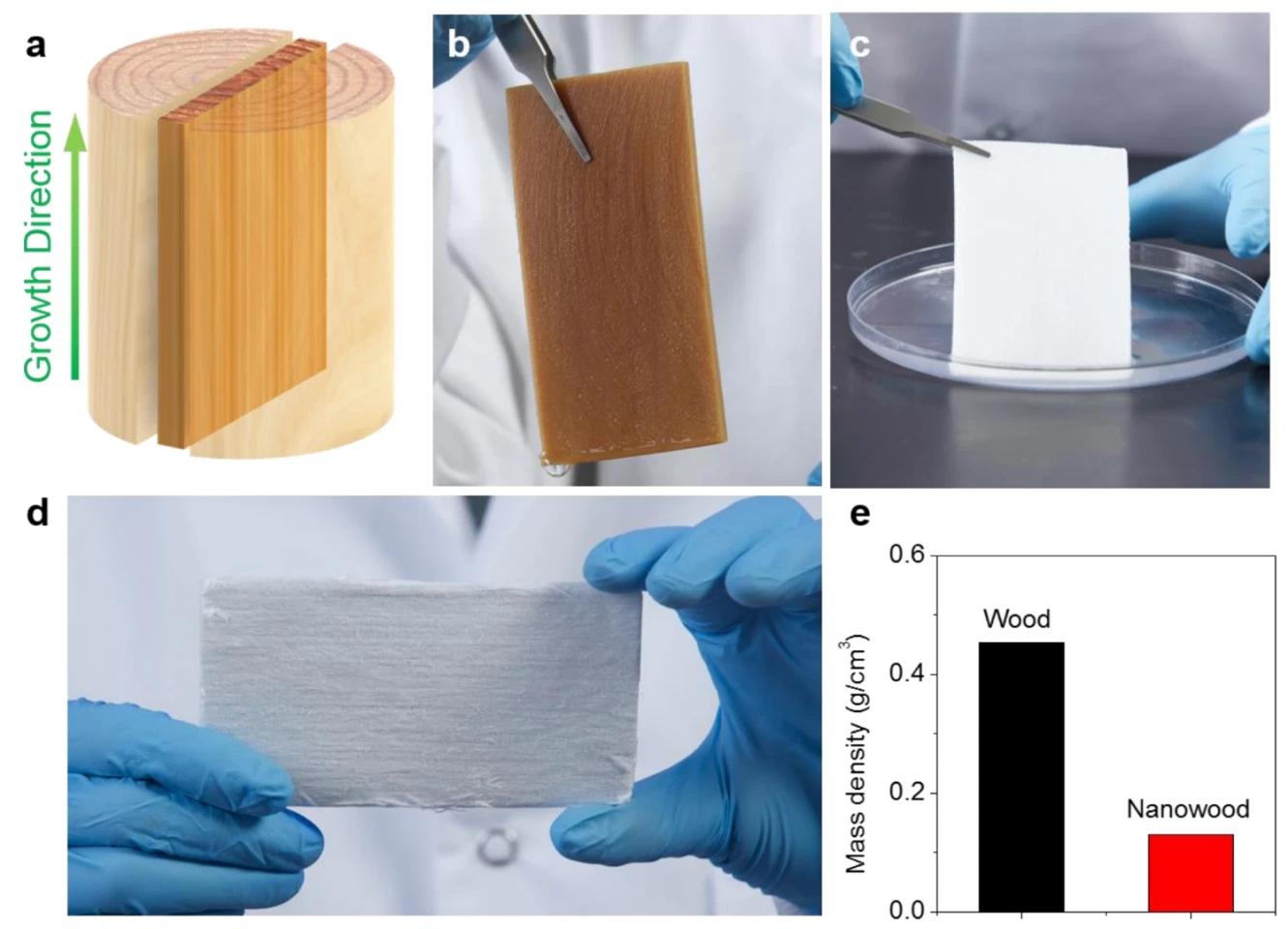

"Nanowood" as the team calls it, is produced by taking certain cuts of regular wood –American basswood in initial trials – and chemically removing all the lignin from it. Lignin contributes the yellow/brown color and hardness you'd normally associate with wood. It's removed entirely when making perfectly white paper that doesn't yellow as it ages.

In fact, the process for producing nanowood is very similar to making paper – the wood is cut, paying special attention to its grain, and then it's boiled in sodium hydroxide and sodium sulfite, then treated in hydrogen peroxide to remove lignin and most of the hemicellulose, and then freeze-dried to maintain the structure of the wood, instead of mashed up as you would to produce paper.

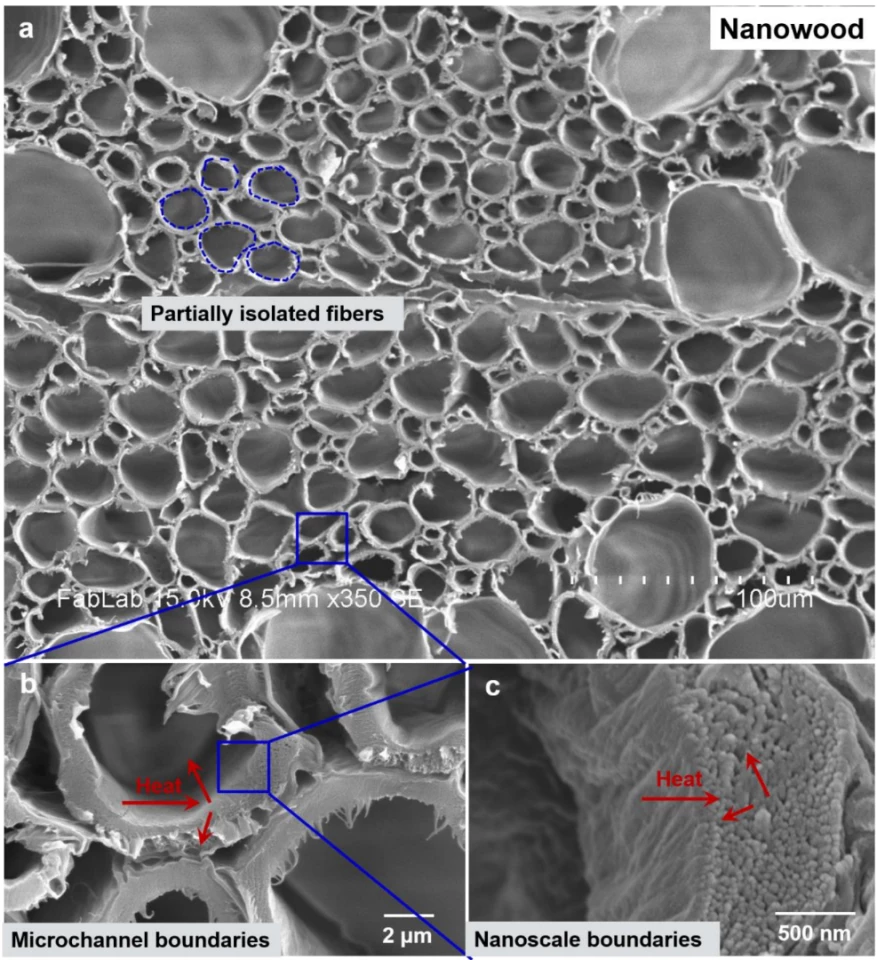

With the lignin taken out of a block of wood, what you're left with is a lightweight, white bundle of cellulose fibers – the scaffold-like structure of the wood itself.

These fibers not only act as extremely effective insulators that are significantly better at blocking heat than the styrene- or silica-based materials typically used in home insulation, but their tubular shape also gives them anisotropic properties. Heat can conduct fairly freely in line with the fibers, but is very effectively blocked in any other direction. So designers can use this property to channel heat around the place as they see fit, and block it elsewhere, just by changing the orientation of the nanowood fibers.

It's strong (30 times stronger than styrofoam in one direction in crush testing), it actively reflects sunlight due to its white color, and its natural cellulose fibers are hypoallergenic. It's also fully biodegradable, and can be produced in a range of shapes and sizes including blocks, sheets and rolls.

It's certainly a fascinating material, but clearly there's a lot more work to be done before it becomes the major home insulation material its creators (led by post-doc student Tian Li and associate professor Liangbing Hu) see it becoming.

For starters, as it's wood-based, it's almost certainly highly flammable, and that'll put a damper on things when it comes time to meet building codes. Secondly, it's not clear how long it takes or how costly the freeze-drying process that separates this from paper production might be. Any commercial application would float or sink based on cost and availability.

If costs can be brought toward that of styrofoam, nanowood could potentially offer a vastly superior version of the styrofoam cup, or a thinner but stronger beer cooler. And who knows, we may indeed one day see it used as a building material.

Source: University of Maryland