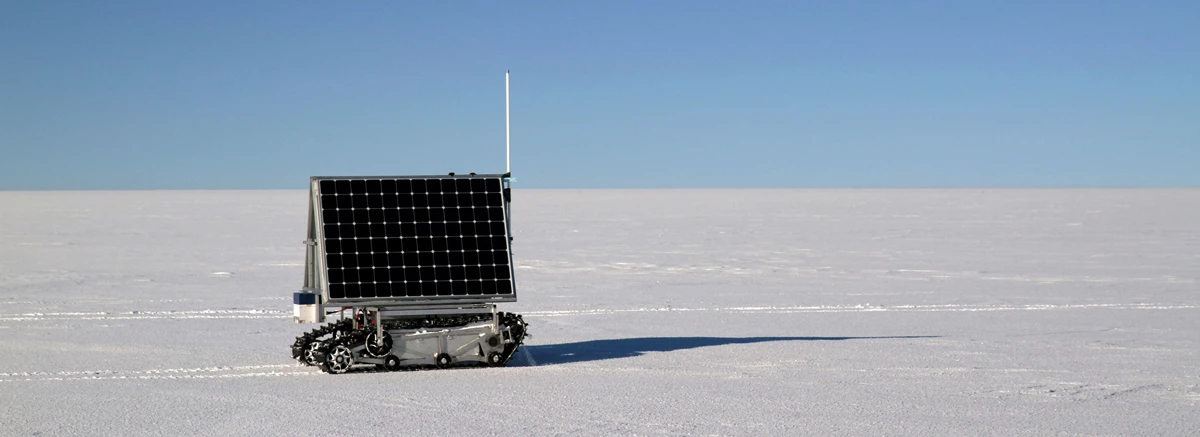

NASA scientists have unleashed a new robot on the arctic terrain of Greenland to demonstrate that its ability to operate with complete autonomy in one of Earth's harshest environments. Named GROVER, which stands for both Greenland Rover and Goddard Remotely Operated Vehicle for Exploration and Research, the polar robotic ranger carries ground-penetrating radar for analysis of snow and ice, and an autonomous control system. All of that is placed between two solar panels and two snowmobile tracks.

GROVER was designed by teams of students attending engineering boot camps at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in the (Northern Hemisphere) summers of 2010 and 2011, and later transferred to Boise State University for fine-tuning with NASA help. The researchers had already run the rover through tests at a beach in Maryland and in the snow in Idaho, but this recent test was the most rigorous. From May 6 to June 8, GROVER was tested at Summit Camp, the highest point in Greenland, and it was the vehicle's first polar experience.

Over five weeks, GROVER collected radar data over 18 miles of icy terrain. Basic mission commands were sent on a daily basis via an Iridium satellite connection, with the robot autonomously those commands out. Operating for 12 hours with each solar charge, the rover independently collected and stored data, while transmitting information about its onboard system performance in real time. Though the radar data is currently stored onboard and retrieved after a mission, the team hopes to eventually switch to a geostationary satellite connection that will allow the transmission of large amounts of data in real time.

The radar system emits a signal that bounces off different layers of the ice sheet. Researchers hope to use this data to study how snow and ice accumulates. Specifically, the team wanted to test the robot's ability to see a layer in the ice sheet that formed after an extreme melt event in the summer of 2012. According to the team, GROVER's radar was able to detect the melt and potentially estimate its thickness.

The research team had expected the robot to work around the clock, but the polar conditions that reached -22° F (-30° C) had a more drastic effect than expected. The 800-lb (363 kg) robot's electronics and battery system couldn't compete with Mother Nature's grasp.

"It’s always more challenging than you thought it was going to be: Batteries don’t recharge as fast and they don’t last as long, and it takes computers and instrumentation longer to boot," explains Hans-Peter Marshall, a geoscientist at Boise State University and science adviser on the project.

That's not to mention the challenges of navigating uneven, icy terrain. The team had to continuously adjust GROVER's speed and power sent to each of its tracks to keep the drone from getting stuck, which contributed to its difficulties holding power.

Though GROVER made many achievements in its first polar test, the team plans to potentially replace components that are hard to manipulate in the cold (like switches and wires), merge the two onboard computers to reduce energy consumption, and use wind generators to create more power. There are even talks of adding a sled to carry additional solar panels.

GROVER wasn’t the only robot seeing the sights in Greenland at the time of testing. Another smaller, non-autonomous robot called CoolRobot built by Dartmouth College was also being put through its paces. Marshall thinks CoolRobot and other polar rovers being developed by different science could one day be working together.

“One thing I can imagine is having a big robot like GROVER with several smaller ones that can move radially outwards to increase the swath GROVER would cover,” Marshall said. “Also, we’ve been thinking about bringing back smaller platforms to a larger one to recharge.”

The video below is a short overview of the team's work with GROVER in Greenland.

Source: NASA