The majority of shark species are threatened with extinction, so it's crucial to protect the "pupping" areas where females give birth to live young. A new satellite-linked device, known as the BAT, lets scientists know the locations of those areas.

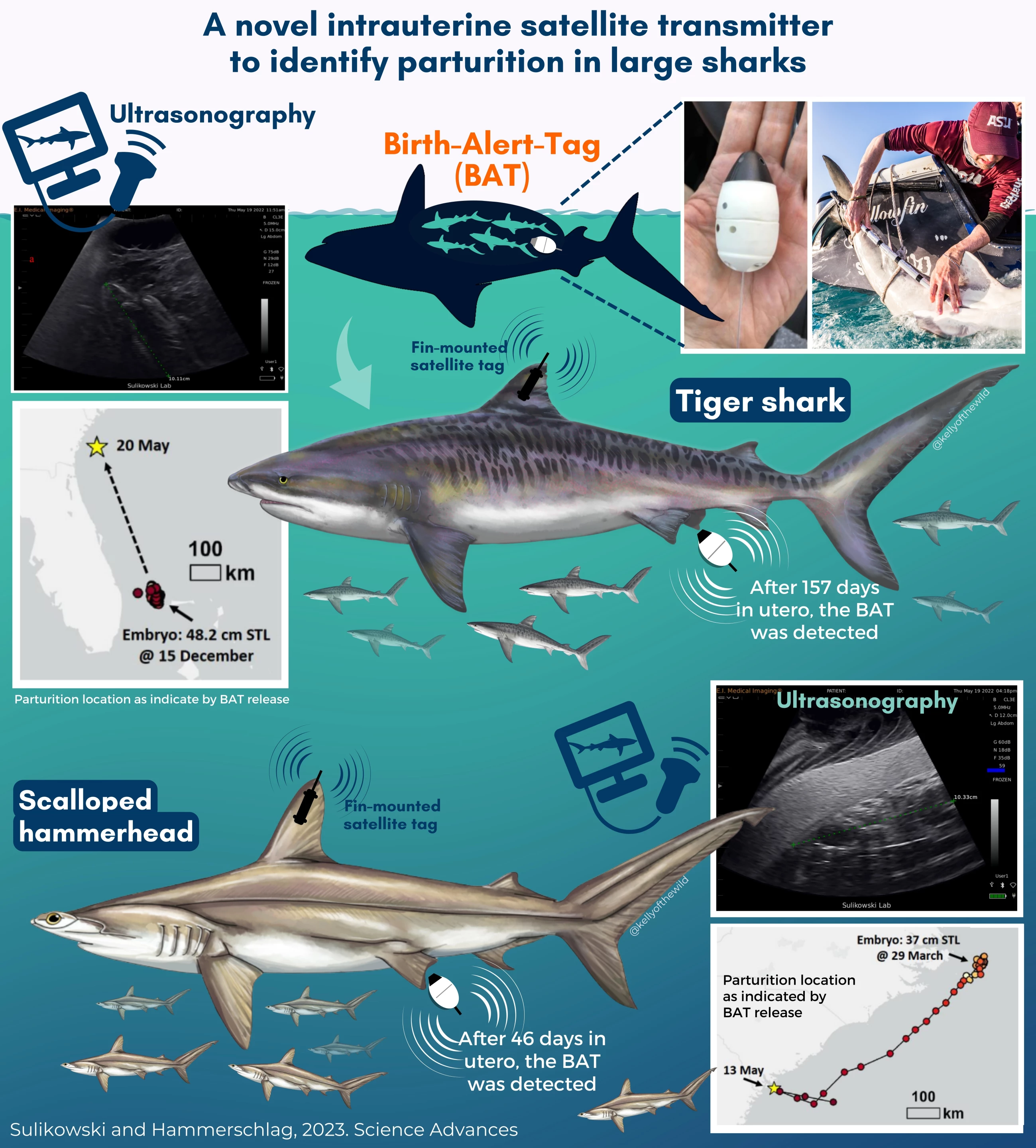

Its name an acronym for "birth alert tag," the BAT is being developed by a team led by Prof. James Sulikowski at Arizona State University and Prof. Neil Hammerschlag at the University of Miami. The egg-shaped device measures 6 cm long by 2.5 cm wide (2.4 by 1 in), and weighs 42 g (1.5 oz) when out of the water.

Here's how it works …

Conservation workers begin by capturing a female shark at sea, bringing her alongside their boat and rolling her over to put her in a torpid state. Utilizing a portable ultrasound machine, they then scan her uterus to see if any embryos are present. If there are, a specialized applicator is used to insert a BAT through her cloacal opening and into her uterus.

The shark is then released, with the BAT harmlessly remaining nestled in amongst the embryos. Once those embryos have developed into pups, and those pups are born, the BAT gets expelled from the uterus along with them.

It proceeds to float to the surface, where an integrated top-mounted wet/dry sensor switches it from standby to transmit mode. Utilizing a flexible antenna, the BAT then starts transmitting signals to orbiting Advanced Research and Global Observation Satellites (ARGOS). It sends these signals at 15-second intervals for approximately two weeks, until its battery dies.

By remotely accessing the ARGOS data from their lab, scientists are thus able to determine where the shark gave birth – and where its growing pups are still located.

The technology has been successfully tested on a female tiger shark which was captured in the Bahamas then gave birth off the coast of Georgia 157 days later, and on a scalloped hammerhead shark which was captured near North Carolina then gave birth off the coast of South Carolina 46 days later.

"We've been trying to do this since we started studying sharks. This is our holy grail. We have really advanced shark science, 20, 30, 40 years," said Sulikowski. "This novel, satellite-based technology will be especially valuable for the protection of threatened and endangered shark species, where protection of pupping and nursery grounds is a conservation priority."

And should you be wondering, Prof. Sulikowski told us that although the BATs aren't retrieved from the sea after each use, the ones tested so far have typically washed ashore and been returned to the scientists.

A paper on the research was recently published in the journal Science Advances.

Source: Arizona State University