While seabed-located cameras are great for tasks such as monitoring wildlife, powering them and retrieving their photos can be challenging. That's where a new MIT-designed camera comes in, as it requires no battery, plus it wirelessly transmits its photos through the water.

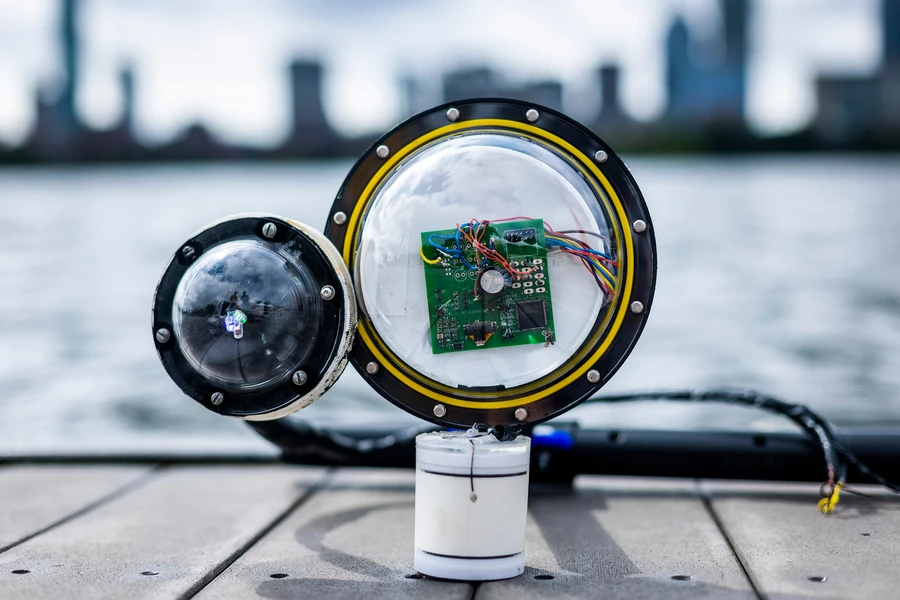

Instead of a battery or a really long power cord, the camera incorporates a series of transducers located around its exterior.

When sound waves from sources such as animals or watercraft reach one of the transducers, the pressure exerted by those waves causes special materials within the transducer to vibrate. Because those materials are piezoelectric, they produce an electrical current in response to the vibrating action. Once enough energy has been produced in this fashion and stored in a super-capacitor, it's used to take a photo.

In order to keep the energy requirements for that task as low as possible, ultra-low-power imaging sensors are used. Unfortunately, though, these sensors only capture grayscale images.

As a means of getting around that limitation, each photo actually consists of three separate exposures – one is taken using red LEDs for illumination, one is taken using green LEDs, and one is taken using blue. Although each exposure appears to be black-and-white, it shows how the subject reflects light in either the red, green or blue color wavelength. As a result, when all three images are subsequently analyzed and combined, they're able to form one composite color photo.

In order to wirelessly receive that digital photo, which is binary-encoded in the form of 1's and 0's, a surface-located transceiver transmits rapid sound-wave signals down through the water to the camera. A module in the camera responds by either reflecting the signal back to the transceiver – indicating a 1 – or by absorbing the signal – indicating a 0. Therefore, by keeping track of which signals are reflected back to the transceiver and which one aren't, it's possible for a topside computer to record a pattern of 1's and 0's that represents the photo.

So far, the technology has a maximum underwater range of 40 meters (131 ft), and has been successfully used for tasks such as documenting the growth of an underwater plant over the course of one week. The MIT team is now hoping to boost both the range and the camera's memory, to the extent that it could ultimately stream images in real time, and even record full-motion video.

A paper on the research was recently published in the journal Nature Communications. Images taken with the camera can be seen in the following video.

Source: MIT