A team of researchers led by MIT's Admir Masic have used a non-invasive technique to determine why one of the famous Dead Sea Scrolls is so well-preserved. The analysis of the 2,000-year-old Temple Scroll provides new insights into not only how ancient parchments were made, but also how to better preserve such artifacts for future generations.

One of the most frustrating problems of history is how fragile the written record is. The various media used to write or print words on, like paper, papyrus, and parchment can be extremely short-lived, even if preserved as carefully as possible. Unless a work is copied and distributed in large numbers, whole libraries can and have been lost over the millennia.

However, sometimes circumstances manage to preserve documents against all odds. Perhaps the most famous example is the Dead Sea Scrolls, which were discovered by accident in 1947 by Bedouin shepherds looking for a lost sheep in the Qumran Caves, which are situated in the Judaean Desert on the northern shore of the Dead Sea.

Soon, a search of the area found 900 documents of ancient Hebrew texts, which had been deliberately buried in 11 caves in the 1st century AD to protect them when the Romans destroyed the settlement of Qumran during the First Roman-Jewish War.

This combination of religious and other documents became a worldwide sensation and there was a rush to unroll and translate many of these scrolls. This brought to light new historical and theological insights, but also caused a lot of unintentional damage to the extremely fragile texts, which were often little more than fragments.

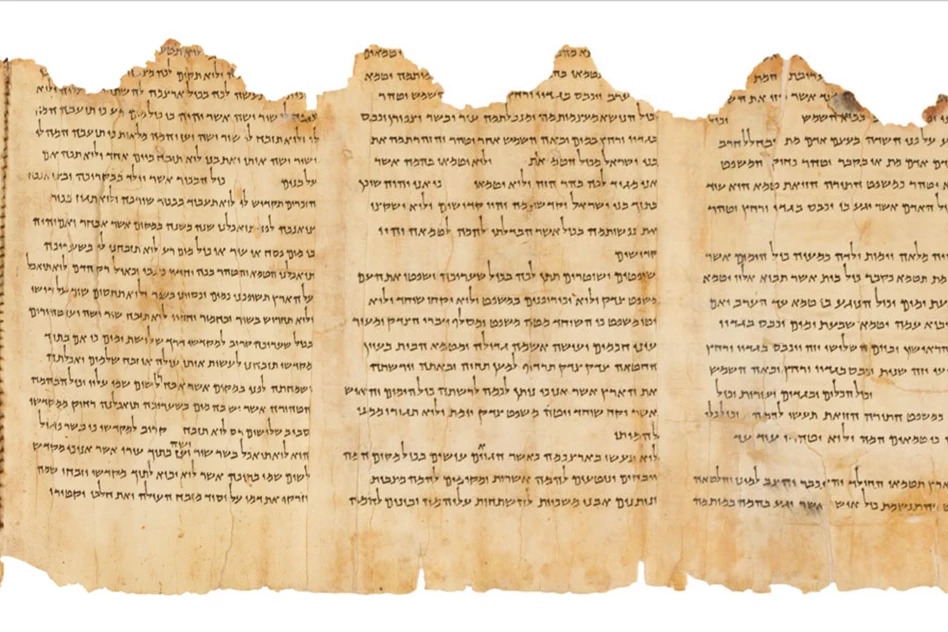

According to MIT, the best preserved of these is the 25-ft (7.6 m) long Temple Scroll, which is the clearest and whitest of the documents despite being made of parchment only 0.1 mm thick. Curious about why this is so, the MIT team decided to take a closer look.

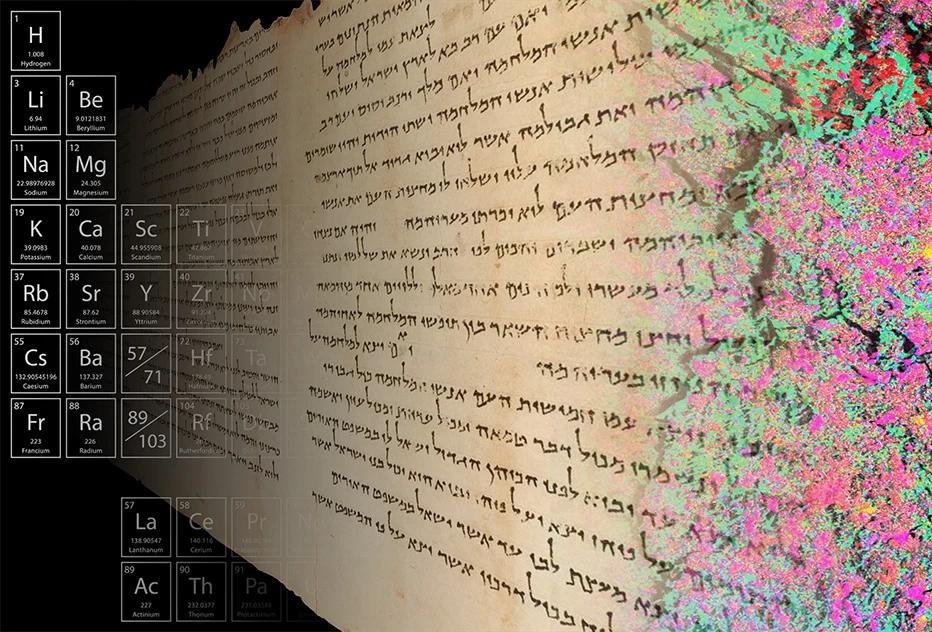

The Temple Scroll is a parchment made up of layers with a collagenous base material and an atypical inorganic overlay. The researchers used non-invasive X-rays and Raman spectroscopies to scan the surface to create a detailed, high-resolution chemical map and found a number of sulfate salts produced by the evaporation of brine.

"We were able to perform large-area, submicron-scale, noninvasive characterization of the fragment," says Masic. "These methods allow us to maintain the materials of interest under more environmentally friendly conditions, while we collect hundreds of thousands of different elemental and chemical spectra across the surface of the sample, mapping out its compositional variability in extreme detail."

Masic says that the Temple Scroll was never treated by conservation experts, so the sulfur, sodium, and calcium found were relatively uncontaminated or disturbed. This is important because parchments are made by either soaking de-haired and defatted animal skins in a lime solution or by enzymatic and other treatments to soften and preserve them. These were then stretched and dried on a frame, then rubbed with salts to create a smoother, whiter writing surface. In the case of the Temple Scroll, it's a very clear and white one that also helped to preserve the document.

The curious thing is that the combination of salts should act like a fingerprint, telling researchers where the brine came from, but it doesn't match the composition of the Dead Sea nor that of salts found on the other scrolls. This means that the Temple Scroll opens up new questions as well as answering others.

“This study has far-reaching implications beyond the Dead Sea Scrolls," says team member Ira Rabin. "For example, it shows that at the dawn of parchment making in the Middle East, several techniques were in use, which is in stark contrast to the single technique used in the Middle Ages. The study also shows how to identify the initial treatments, thus providing historians and conservators with a new set of analytical tools for classification of the Dead Sea Scrolls and other ancient parchments."

The research was published in Science Advances.

Source: MIT