Scientists see massive potential in the possibility of manipulating or mimicking the natural process of photosynthesis, which could lead to new forms of clean fuel, ways to soak up carbon dioxide or aid in drug discovery. New research has tugged this technology in an interesting new direction, with a team at Sweden’s Lund University demonstrating how carefully spaced mirrors can be used to trap light and supercharge photosynthetic harvesting.

Photosynthesis is the process through which plants turn sunlight, carbon dioxide and water into chemical energy. Artificial forms of photosynthesis might recreate this by using solar cells and electrolyzers to split water into hydrogen, or translucent materials shaped into artificial leaves that turn sunlight into energy through chemical reactions.

We’ve also seen promising advances when it comes to supercharging photosynthesis in living organisms, such as special electrode designs that boost the energy-harvesting capabilities of photosynthetic bacteria. The new research from Lund University follows a similar line of thinking, with the scientists working with light-harvesting complexes from photosynthetic purple bacteria.

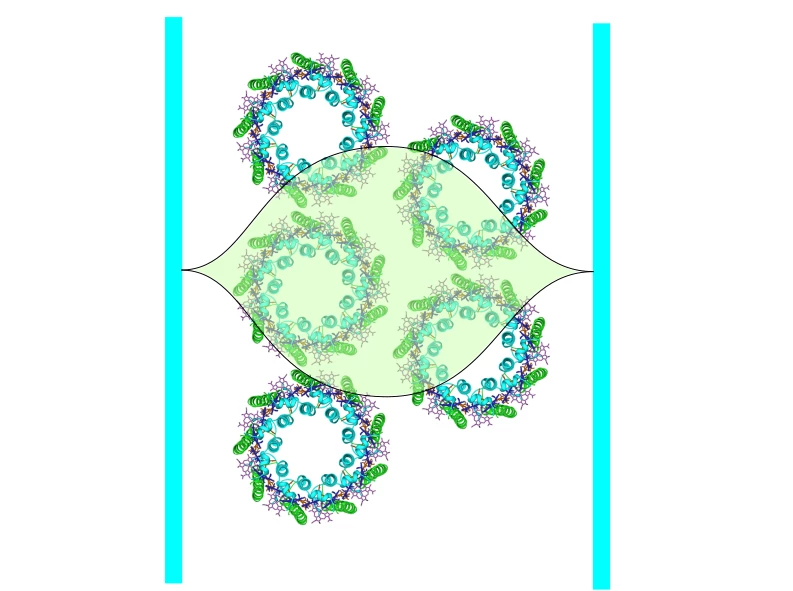

These complexes are made up of protein and chlorophyll molecules that transfer light energy to another complex known as the reaction center, which in turn drives the cellular metabolism of the organism. These “antenna” complexes were placed in between two optical mirrors, which were spaced mere nanometers apart.

“We have inserted so-called photosynthetic antenna complexes between two mirrors that are placed just a few hundred nanometers apart as an optical microcavity,” said Tönu Pullerits, professor of chemical physics at Lund University. "You can say that we catch the light that is reflected back and forth between the mirrors in a kind of captivity.”

By studying the process through ultrafast laser spectroscopy, the scientists observed stronger interactions between the bouncing light and the antenna complexes, and in turn a “significant prolongation of the excited state lifetime." This can in turn create a ripple effect that accelerates the transfer of energy, ultimately making one of the key elements of photosynthesis faster and more efficient.

“We have now taken a couple of initial steps on a long journey,” said said Pullerits. “You can say that we have set out a very promising direction.”

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Lund University