This space-rock oddity has long puzzled scientists for its rather non-asteroid-like behaviors, and it’s just revealed yet another curious characteristic.

In 2009, NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) craft identified that asteroid 3200 Phaethon was doing something peculiar in orbit, brightening and growing a substantial tail as it reached its closest point to the Sun on its 524-day orbit.

This was already a strange occurrence, since comets have tails, due to their icy make-up, not rock-and-metal asteroids. It’s long been thought to be dust that had been expelled from the asteroid’s surface.

Now, scientists have discovered that there’s no dust in sight; it is, in fact, an impressive tail made up of sodium gas.

“Our analysis shows that Phaethon’s comet-like activity cannot be explained by any kind of dust,” said lead author Qicheng Zhang, PhD student at the California Institute of Technology. “Comets often glow brilliantly by sodium emission when very near the Sun, so we suspected sodium could likewise serve a key role in Phaethon’s brightening.”

An earlier study had landed on sodium being the cause of ‘fizzing’ on the asteroid’s surface. When it’s close to the Sun, Phaethon – which is nearly 3.9 miles (6.3 km) in diameter – has a surface temperature of around 1,390 °F (750 °C), which vaporizes certain substances.

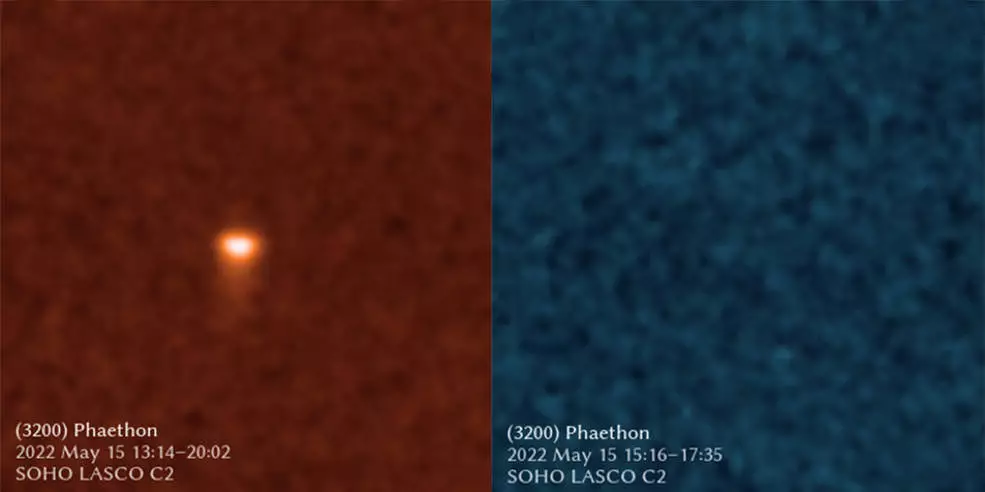

The discovery was made with the use of two NASA solar observatories. The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft was employed to observe the asteroid through two filters, which could identify sodium and dust, respectively. The researchers then hit the archives of STEREO and SOHO imaging and found the occurrence of Phaethon’s tail on 18 solar approaches between 1997 and 2022.

The SOHO filters confirmed suspicions: the asteroid’s tail was obvious and bright when using the sodium-detecting lens, and scientists could see how it changed shape and intensity as it moved along its path. No evidence of dust was observed with the other filter.

“Not only do we have a really cool result that kind of upends 14 years of thinking about a well-scrutinized object, but we also did this using data from two heliophysics spacecraft – SOHO and STEREO – that were not at all intended to study phenomena like this,” said team member Karl Battams of the Naval Research Laboratory.

The discovery adds to the mystery of Phaethon, which orbits closer to the Sun than any other other named asteroid, is one of the few to appear blue on the surface and is the source of the annual Geminid meteor shower. Comets are generally responsible for meteor showers.

In 2017, Phaethon – identified in 1983 and named after the son of the Sun god Helios in Greek mythology – whizzed past Earth, however it was still 6.4 million miles (10.3 million km) from the planet. It won’t head back this way again until 2093.

The study was published in The Planetary Science Journal.

Source: NASA