On July 26, 1971, at 9:34 am EDT, Apollo 15 lifted off the Pad A of Launch Complex 39 at the Kennedy Space Center on the first true lunar exploration mission. Using an improved Lunar Module, the ninth crewed Apollo mission and fourth lunar landing featured the first vehicle to drive on the Moon, allowing astronauts to roam farther than ever before.

Three days after launch, on July 29, Apollo 15 entered lunar orbit. The twin spacecraft consisted of the Command Service Module (CSM) Endeavor, named after Captain James Cook's famous exploration vessel, and the Lunar Module (LM) Falcon, named after the feathered mascot of the US Air Force Academy in honor of Apollo 15's all-Air-Force crew.

Aboard the craft were Colonel David Randolph Scott, Mission Commander; Major Alfred Merrill Worden, Command Module Pilot; and Lieutenant Colonel James Benson Irwin, Lunar Module Pilot. Scott was a veteran astronaut, who had been the pilot of Gemini 8 and Command Module Pilot on Apollo 9, which was the first flight test of the LM. Worden and Irwin were both rookies making their first spaceflights.

Apollo 15 marked a more ambitious phase of the US Moon program. Where Apollo 11 through 14 were concerned with reaching the Moon and learning more about how to make precision landings, Apollo 15 was the first "T mission" tasked with making long exploration treks over the lunar surface, and conducting intensive scientific investigations in both the landing areas and in lunar orbit.

These missions would see the introduction of scientist astronauts and more emphasis on science training for the crews, with the astronauts making extensive field trips to Moon-like regions on Earth to study geology and practice for the first deep-core drilling on the Moon.The LM & CSM modifications

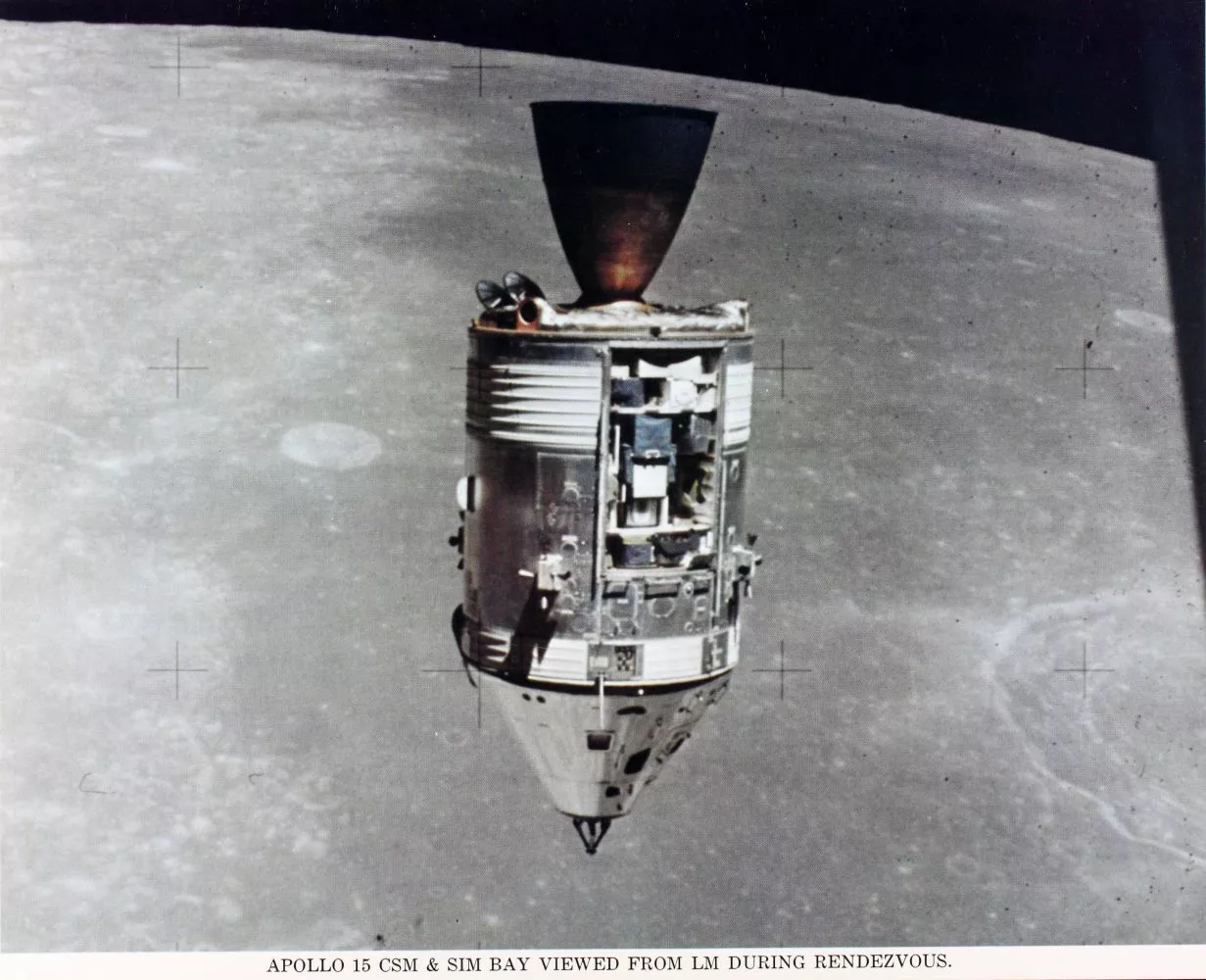

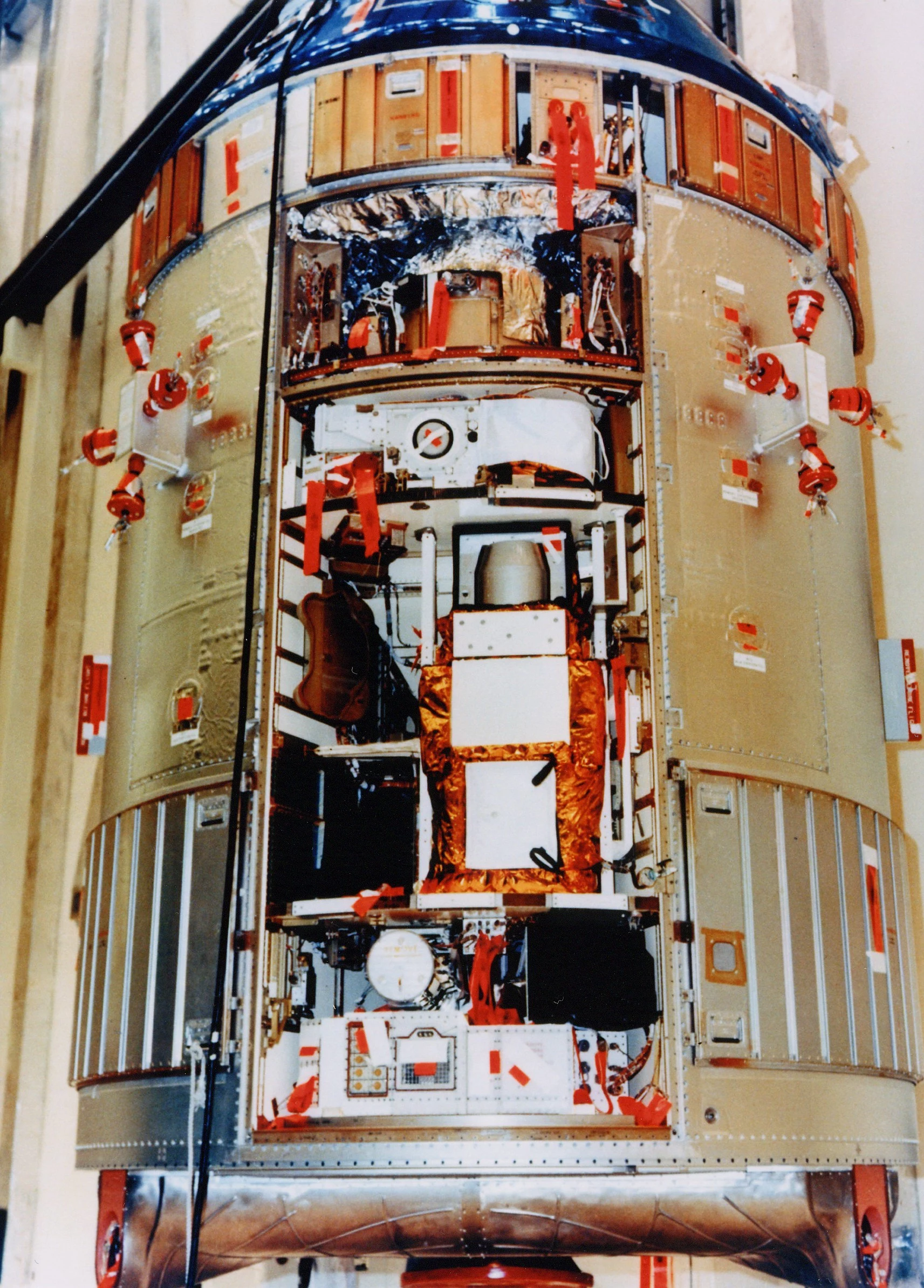

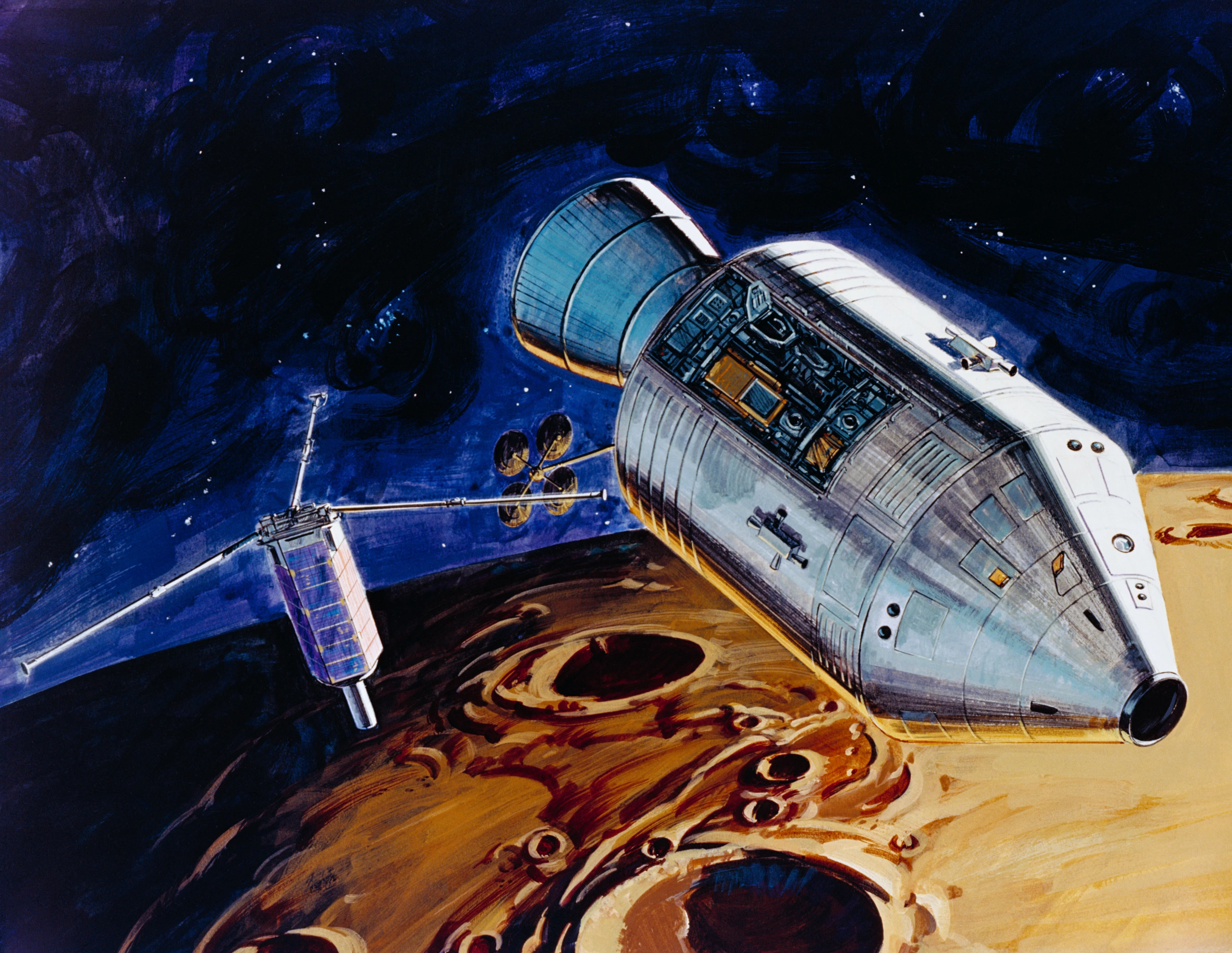

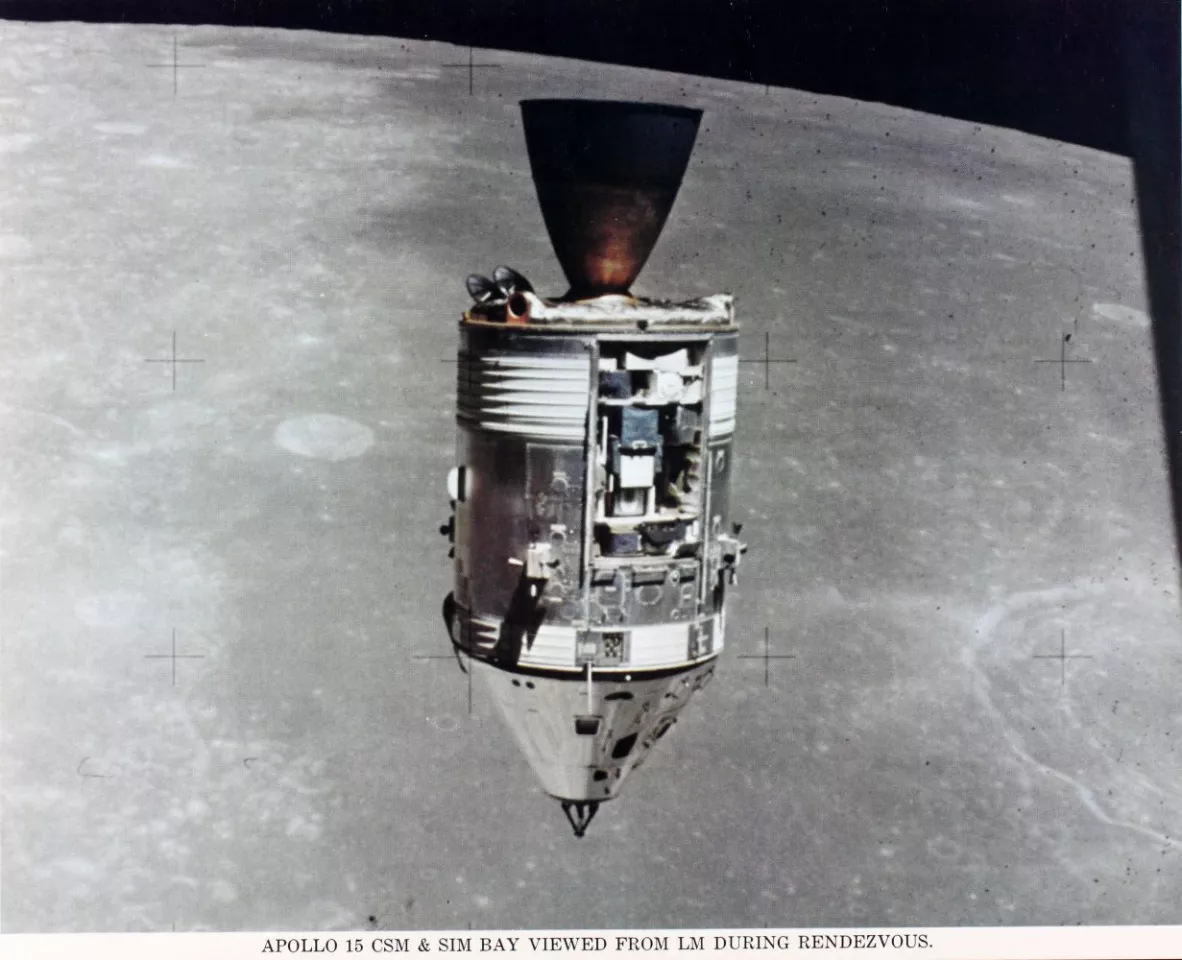

To help with the new exploration program, Apollo 15 was equipped with augmented versions of the CSM and LM. The Service Module was upgraded to include an instrument bay to hold a variety of sensors for studying the Moon from orbit, as well as a sub-satellite launcher to place a robotic payload in lunar orbit.

Meanwhile, the LM was 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) heavier than the older versions, with the inclusion of larger fuel and oxygen tanks, extended engine bells on both the descent and ascent stages, and larger battery banks and solar cells. This allowed the Lunar Module to stay on the surface for almost twice the length of time and carry a larger payload, which included the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV).

In addition to these, Scott, Worden, and Irwin wore new spacesuits that were tailored for more mobility and were easier to don and remove thanks to an angled zipper. When walking on the surface, Scott and Irwin would be wearing improved life support backpacks that carried more oxygen and longer-life batteries.Landing

The voyage from Earth had been marked by only minor problems and, aside from having to reconnect a loose umbilical cord, the Falcon LM undocked from Endeavour only 25 minutes behind schedule. The landing site was much more challenging than on previous missions thanks to lessons learned in the first landings. Where Apollo 11, 12, and 14 landed near the equator and in the lowlands of the lunar mares, Apollo 15 set down on July 30 in the higher latitudes, in the highlands of the lunar Apennines mountain range on the edge of Mare Imbrium near Hadley Rille, which is a collapsed lava tube that looks like a channel.

After landing and securing the LM, Scott made an unorthodox EVA. Instead of leaving the spacecraft through the front hatch, he opened the top hatch that's used to dock with the Command Module. Standing with his helmeted head out, he had a high vantage point from where he could scan the landscape for half an hour while taking panoramic photographs.

"As I stand out here in the wonders of the unknown at Hadley, I sort of realize there's a fundamental truth to our nature," said Scott as he left the LM later to set foot on the Moon for the first proper EVA. "Man must explore, and this is exploration at its greatest."The Lunar Rover Vehicle

After deploying a new set of nuclear-powered scientific instruments on the surface, the American flag was planted, and an improved high-gain communications antenna was set up. The astronauts then turned their attention to deploying the Lunar Rover Vehicle (LRV).

NASA had been toying with the idea of sending a rover to the Moon for over a decade, though they were hampered by a lack of knowledge about the nature of the lunar surface and the primitive nature of robotics in the 1960s that made autonomous operations impossible.

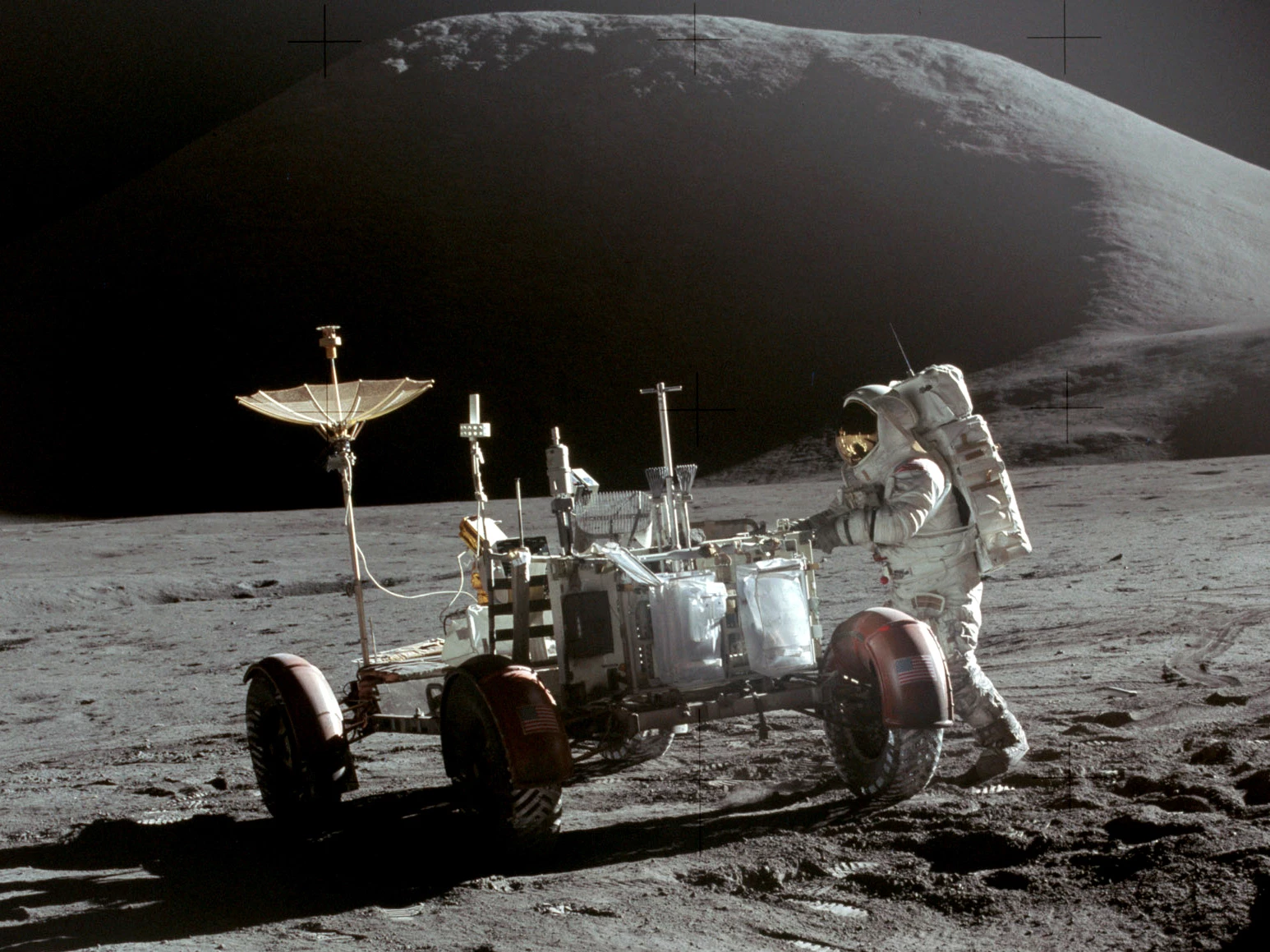

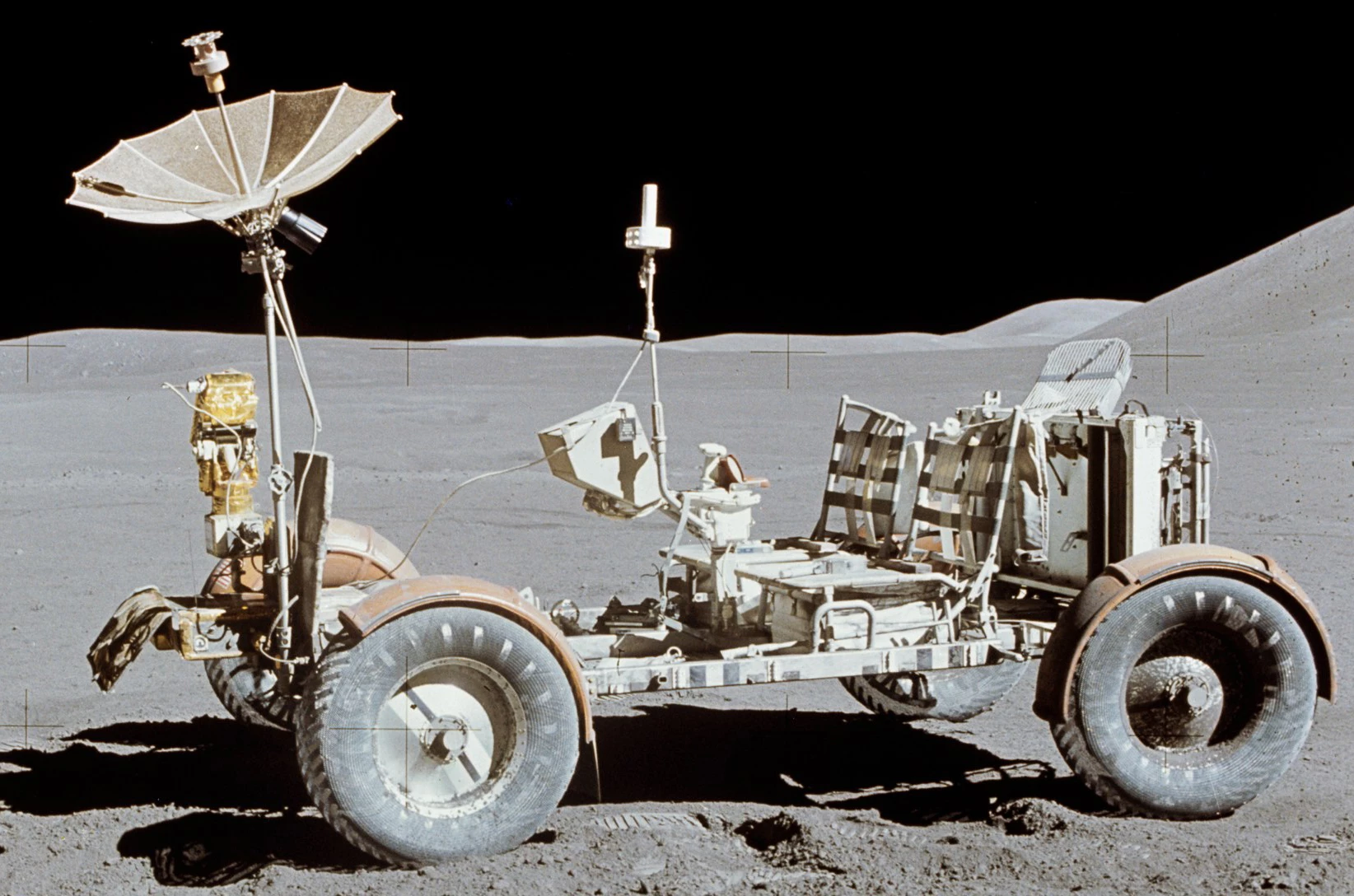

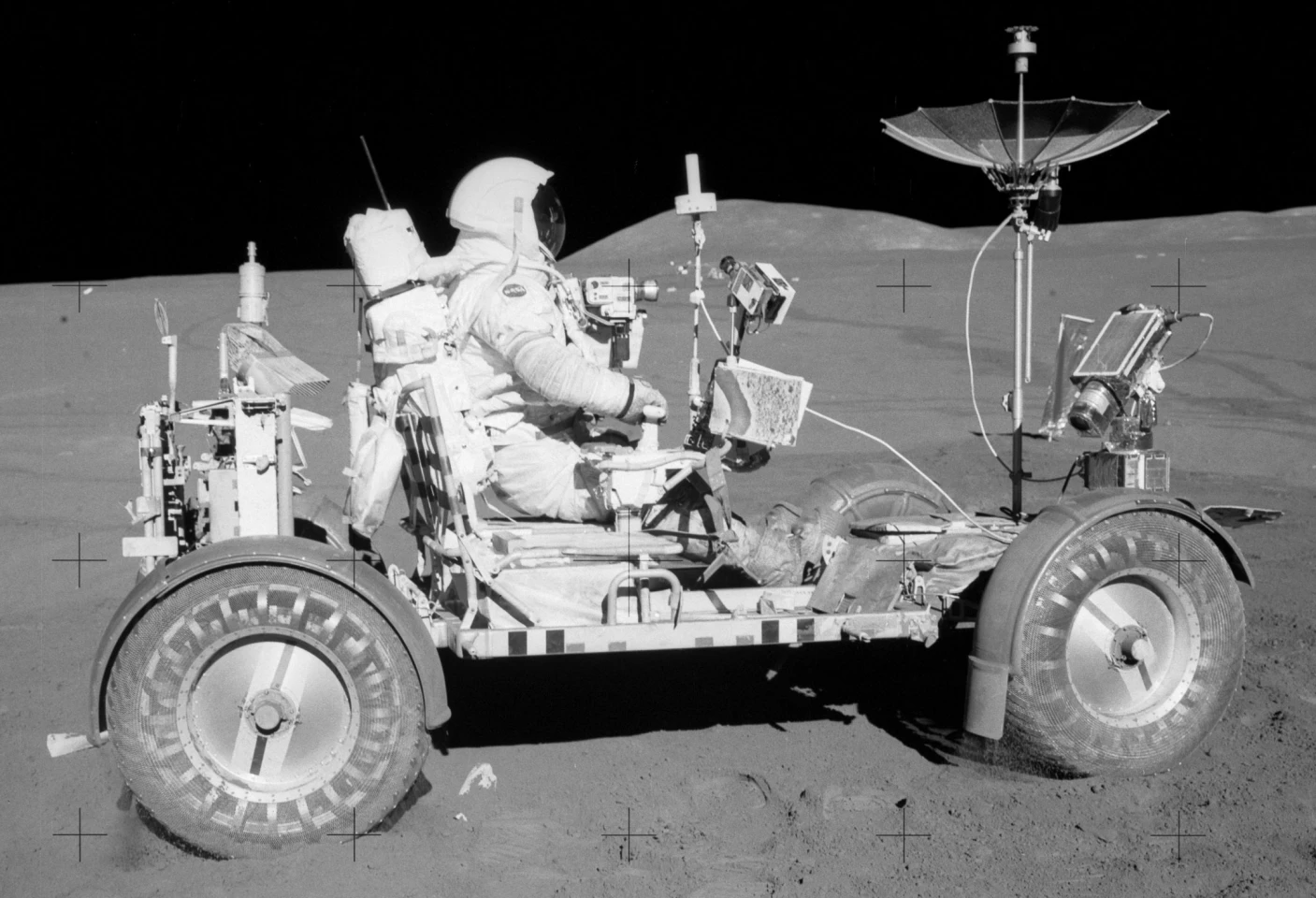

Now that astronauts had made it onto the Moon, NASA hired Boeing to create an electric car to allow the explorers to travel far beyond the immediate vicinity of the lander. With the contract signed in October 1969, the company had only 17 months to design, build, and test the rover, which not only had to be able to fulfill its mission requirements, but also be light enough and fold up small enough to fit inside the LM's new payload bay.

The result was a four-wheeled car that resembled a dune buggy, hence its nickname of "moon buggy." It was 10 feet (3 m) long and had a wheelbase measuring 7.5 ft (2.3 m). On Earth, it weighed 460 lb (210 kg), but on the Moon it tipped the scales at 76 lb (34 kg). This was a major headache for the engineers tasked with building the vehicle when they weren't sure how it would behave in low gravity, especially when loaded down with 1,080 lb (500 kg) – or 180 lb (82 kg) on the Moon – of passengers and cargo.

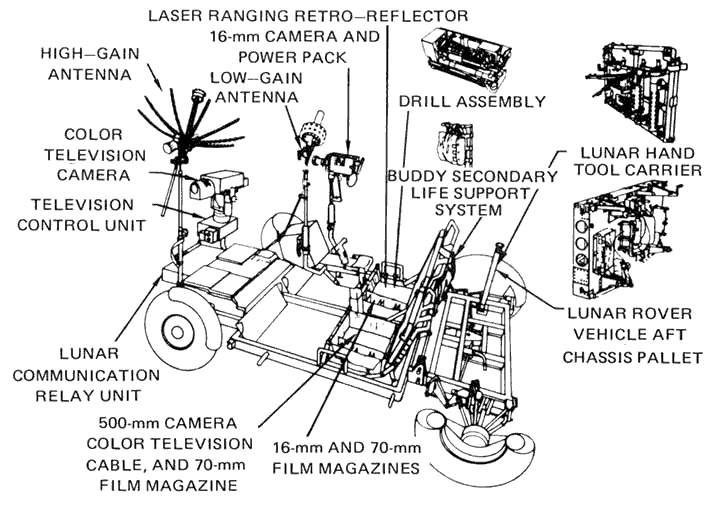

Though it looked simple, the Rover incorporated some surprisingly sophisticated features, including two 36-V battery systems to power the vehicle independently for 78 hours or 35 nm (41 mi, 65 km), front- and rear-wheel steering, a television camera that could be remotely controlled from Earth, a high-gain communications link direct to Earth, and a gyrocompass.

The gyrocompass was particularly clever because the Moon doesn't have a magnetic field, so in order for the device to discern true north there was a sun compass on the dashboard that allowed NASA to calculate north by taking readings on the sun's shadow, in the same way polar explorers do on Earth near the magnetic poles.

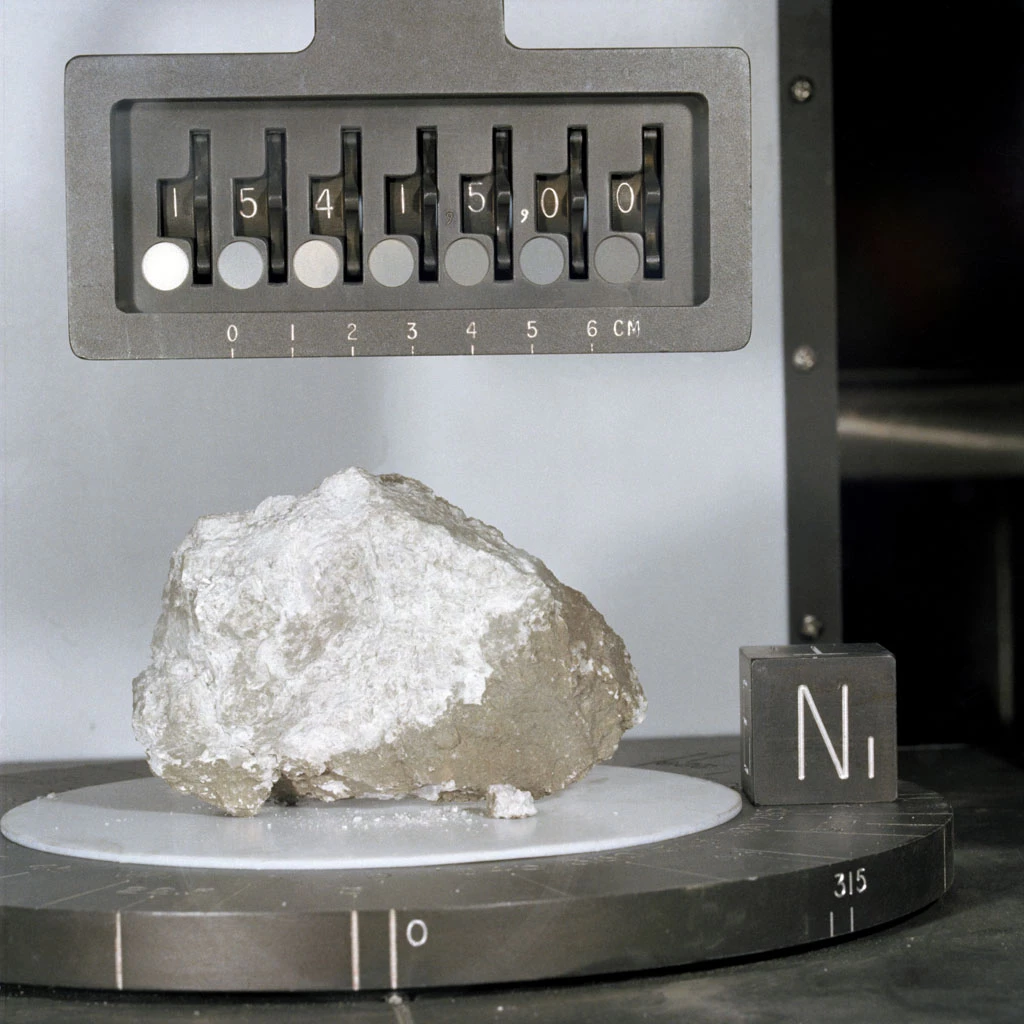

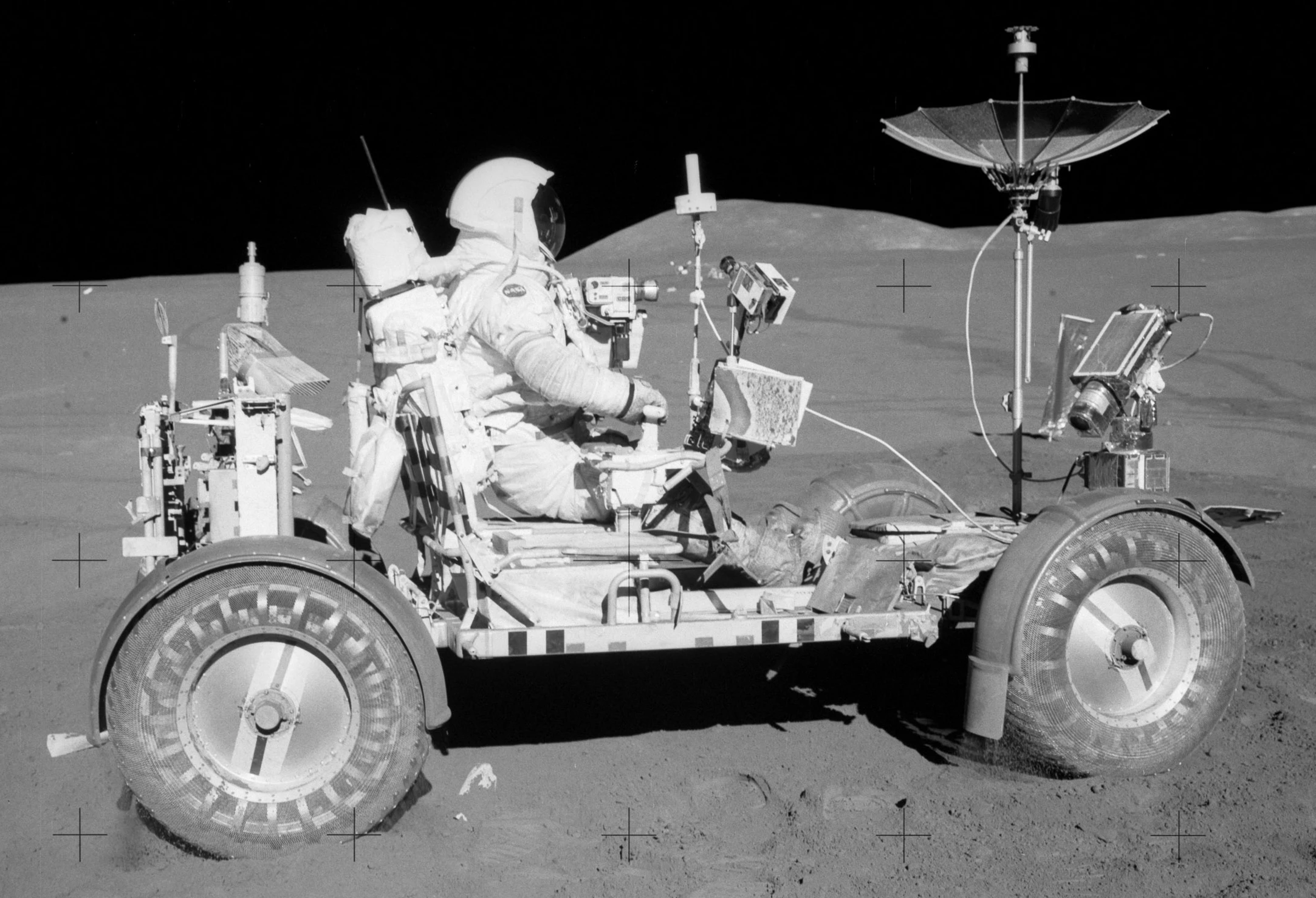

Over three EVAs, the Rover covered a total of 17.25 miles (27.76 km) as Scott and Irwin stopped from time to time to take photos and collect 170.44 lb (77.31 kg) of geological samples, including what is now called the Genesis Rock, which is believed to be 4.46 billion years old and was part of the early lunar crust.

Despite some early technical glitches, the astronauts quickly became enthusiastic about the Rover and recognized how useful the vehicle was for exploration of the Moon – not the least because it was much easier for the astronauts to ride than walk, resulting in less fatigue, less wear and tear on their suits, and reduced oxygen consumption.The hammer, the feather, and the memorial

Another memorable aspect of Apollo 15 were the small demonstrations conducted by the astronauts. In a spare moment during an EVA, Scott carried out an experiment first proposed by Galileo centuries ago. Standing in front of the television camera, the people back on Earth saw him holding a hammer in one hand and a feather in the other. Releasing both at the same time, they fell at the same rate, showing what Galileo theorized about how fast something falls in a vacuum is dependent on gravity, not weight.

On a more somber note, when Scott drove the Rover away from the LM on the last EVA so it could transmit video of the spacecraft's liftoff, he parked the vehicle and placed a small aluminum statue on the ground, along with a plaque bearing the names of the 14 US and Soviet astronauts and cosmonauts who had died in the course of space explorations. Though he did this privately, he revealed the memorial in a post-mission press conference.Subsatellite and spacewalk

While Scott and Irwin were on the surface, Worden was in the Command Module photographing the Moon and gathering X-ray and gamma ray measurements. After Falcon's Ascent Module docked with Endeavour on August 2, 1971, Scott and Irwin transferred to the CSM along with the rock samples and film magazines. The Ascent Module was then jettisoned and made a controlled burn to crash on the Moon.

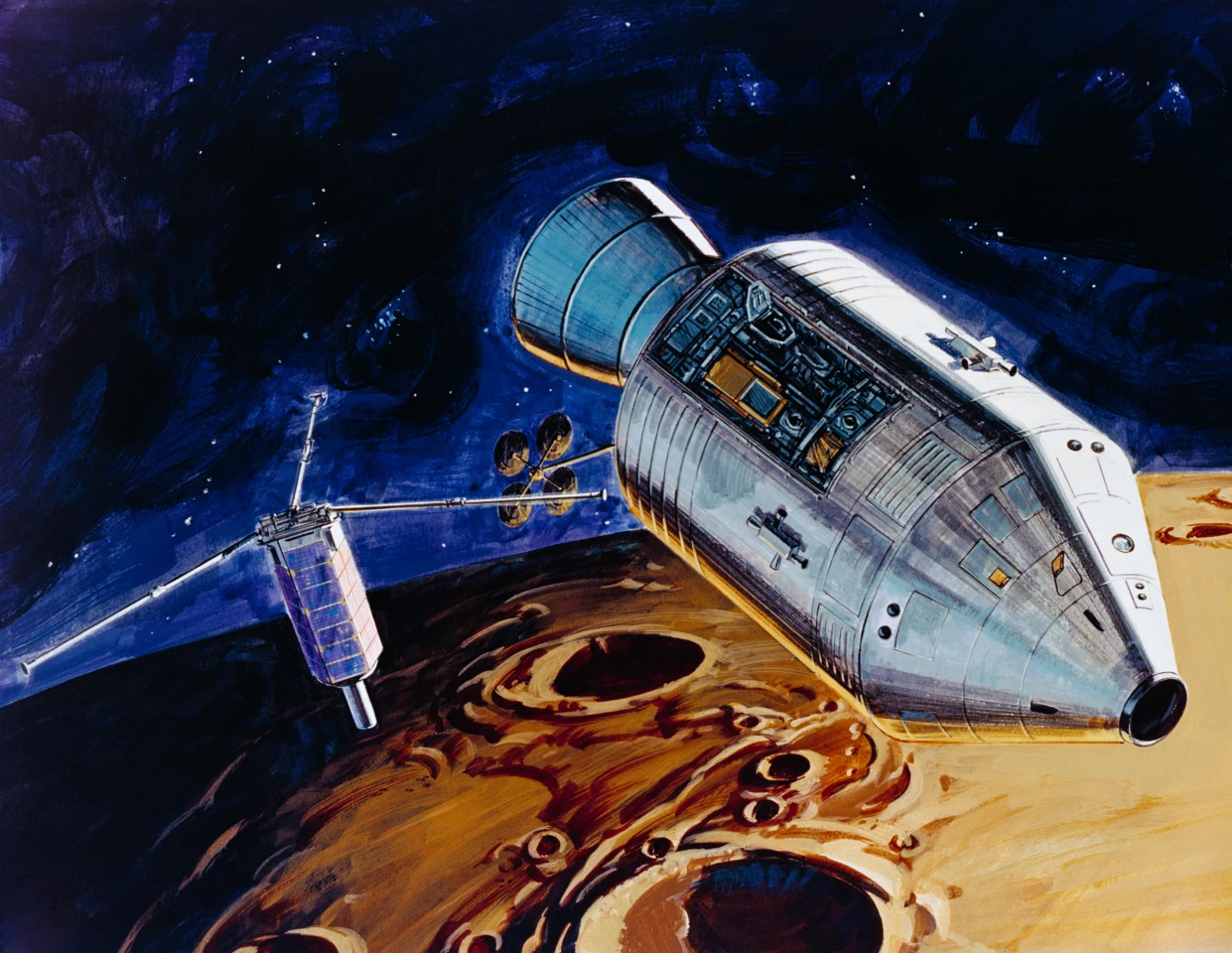

Endeavour remained in lunar orbit until August 4, during which time the subsatellite was launched using a spring to push it away. The little satellite orbited the Moon until 1973, studying the plasma, particle, and magnetic field environment of the Moon and mapping the lunar gravity field.

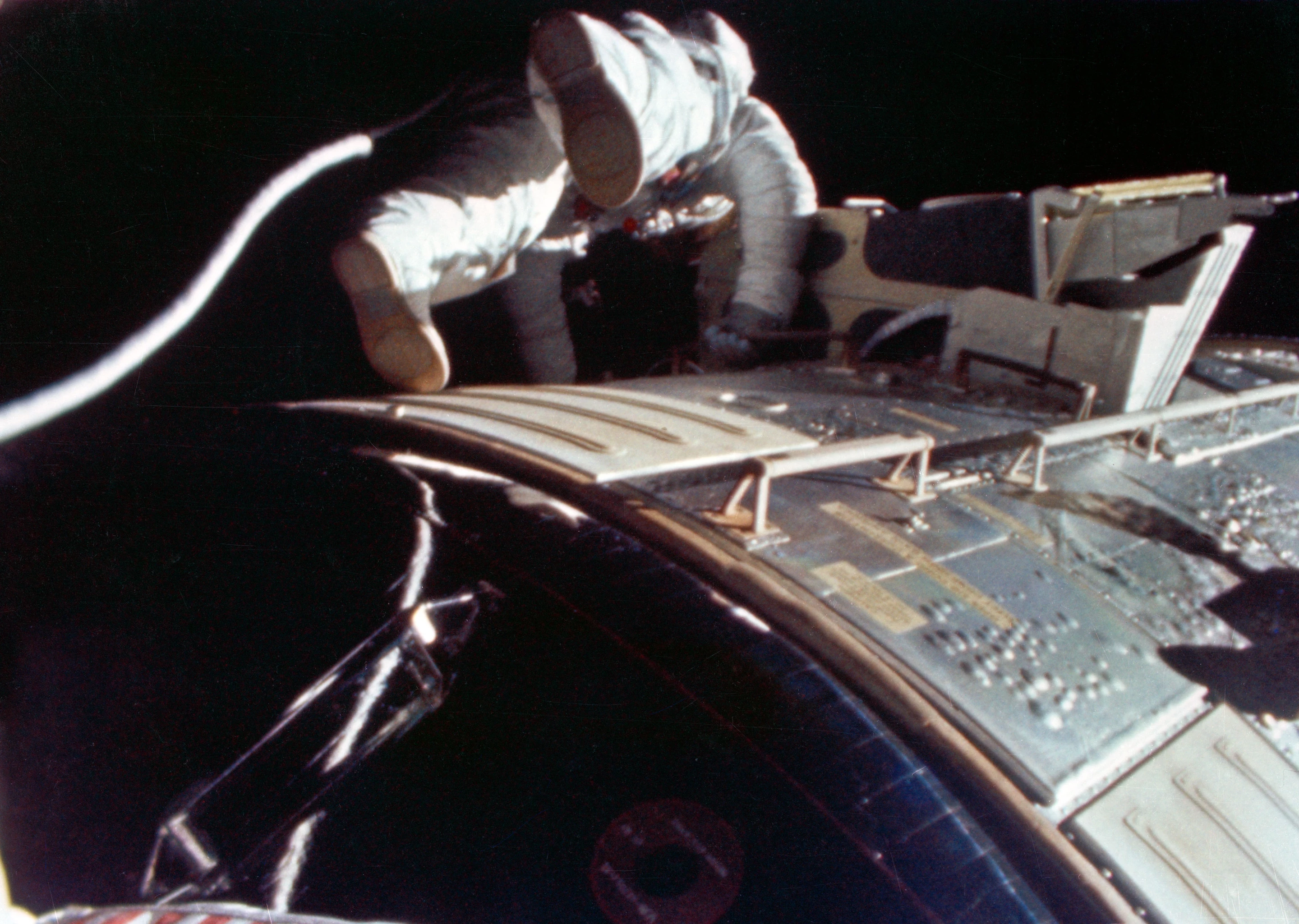

After leaving lunar orbit, the spotlight was now on Worden, who conducted the first deep-space spacewalk when he left the Command Module and spent 39 minutes moving along handholds to the Service Module and back three times to recover film canisters from the service bay cameras. Meanwhile, Irwin stood in the Command Module hatch, taking photos of the Command Module Pilot.

Return to Earth

On the trip back to Earth, the crew of Apollo 15 broke the record from the longest Apollo flight to date. On August 7, 1971, Endeavour's Command Module separated from the Service Module and splashed down in the Pacific Ocean north of the Island of Oahu before being recovered by the aircraft carrier USS Okinawa. The mission clocked in at 12 days, seven hours, 11 minutes, 53 seconds.

Aside from making automotive history and ushering in a new phase of lunar exploration, Apollo 15 revived the flagging interest in the US space program, which was becoming increasingly unpopular in the face of the costs of the Vietnam conflict, and the paradox of the high level of professionalism by NASA making incredibly ambitious and dangerous Moon missions seem dull and almost routine.

Already three long-term surface missions had been cancelled, which put increasing pressure on the last two missions that were looking more and more likely to not only be the last of the Apollo missions, but the beginning of a long hiatus in human spaceflight for NASA.