A new study by the Planetary Science Institute and UCLA confirms that there are areas in the lunar south polar region where frozen carbon dioxide could exist, raising hopes that there could be significant resources to support future Moon missions.

With an international raft of government and private crewed and robotic missions to the Moon lined up for the next decade at least, finding lunar resources to support expeditions and outposts has become a top priority.

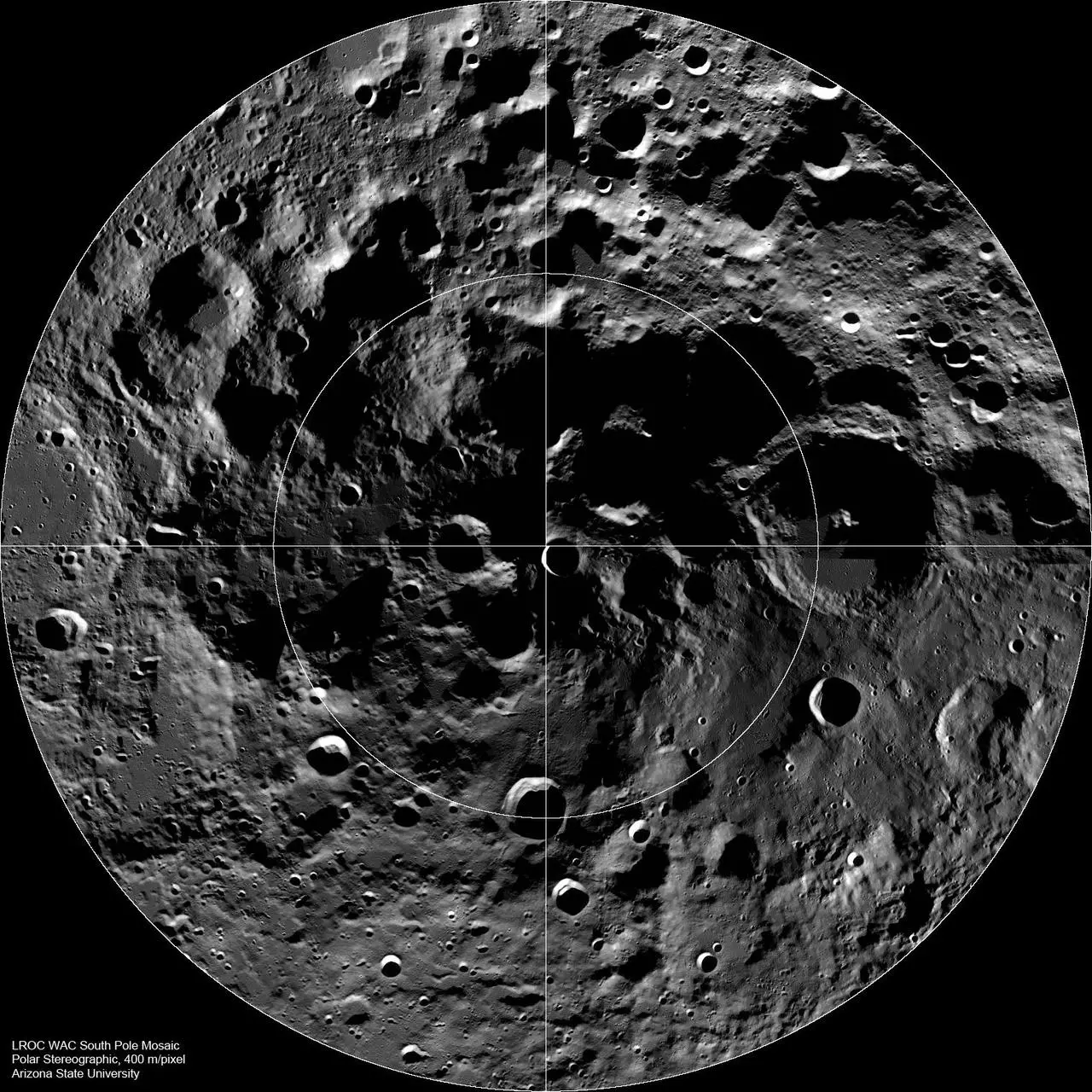

One bit of good news in recent years has been the confirmation of the presence of water ice in perpetually shadowed craters around the lunar south pole, but the question has remained as to how cold these craters are? If never get warmer than minus 110 K (-267 °F, -163 °C), then water ice can be present, but if the top temperature is under 50 K (-370 °F, -223 °C), then solid carbon dioxide can be present without any danger of sublimating away into the vacuum.

For decades, this has remained an open question, but the new study used 11 years of surface temperature data collected by the Diviner radiometer aboard NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), combined with calculations of lunar months (lunations) and lunar seasons to find a definitive answer.

According to the results, 204 km² (79 miles²) of the polar region not only remain very cold, but are colder than the coldest areas on Pluto. In these areas, even in the lunar summer the temperatures never rise above 60 K (-352 °F, -213 °C). The single largest area is in Amundsen Crater, which covers 82 km² (32 miles²).

The team stresses that these super-cold temperatures do not show that carbon dioxide is present, but it does open the way to further exploration. If it is found, it would give future missions a resource for producing steel, rocket fuel, and biomaterials to sustain human outposts.

"I think when I started this, the question was, ‘Can we confidently say there are carbon dioxide cold traps on the Moon or not?’" says Norbert Schörghofer, a planetary scientist at the Planetary Science Institute. "My surprise was that they’re actually, definitely there. It could have been that we can’t establish their existence, [they might have been] one pixel on a map … so I think the surprise was that we really found contiguous regions which are cold enough, beyond doubt."

The research was published in Geophysical Research Letters (PDF).

Source: American Geophysical Union