Astronomers have observed a bright flash of light from space, which appears to have come from a collision between two black holes. And that’s surprising, considering that black holes are famously dark objects.

Black hole mergers are becoming pretty commonplace detections, with several dozen of them discovered in the last five years. But so far, all of them have been detected in the form of gravitational waves – distortions in the very fabric of space and time caused by the immense gravity of the collision.

And normally, these events are only picked up by gravitational wave detectors like LIGO. After all, not even light itself can escape a black hole, so there’s not much for other observatories to see. So far, only one gravitational wave event has also been accompanied by other signals, giving off a burst of light, radio, X-rays and gamma rays, but this was a collision between two neutron stars.

Now, astronomers have spotted the unspottable – light from an apparent black hole collision. The event started like any other. On May 21, 2019, LIGO and Virgo detected gravitational waves from a pretty stock standard black hole merger.

It wasn’t until later that scientists realized they’d captured something more. Months later, a team was examining archival data from Caltech’s Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) and discovered a flare of light that began a few days after the gravitational wave event, and faded over the next few weeks.

The location of the event appeared to be near a supermassive black hole, but the scientists don’t believe that was the culprit. Flares from these huge objects are common, but the prior 15 years of data show that this one was an anomaly.

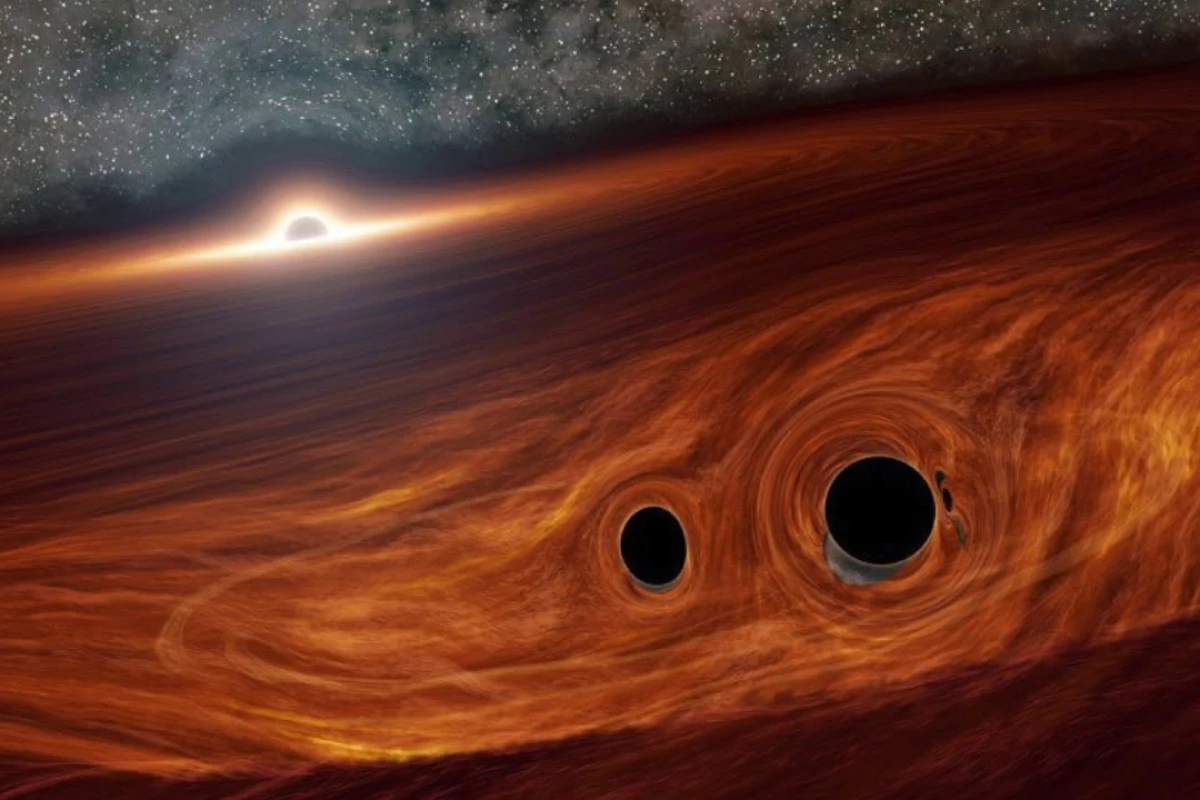

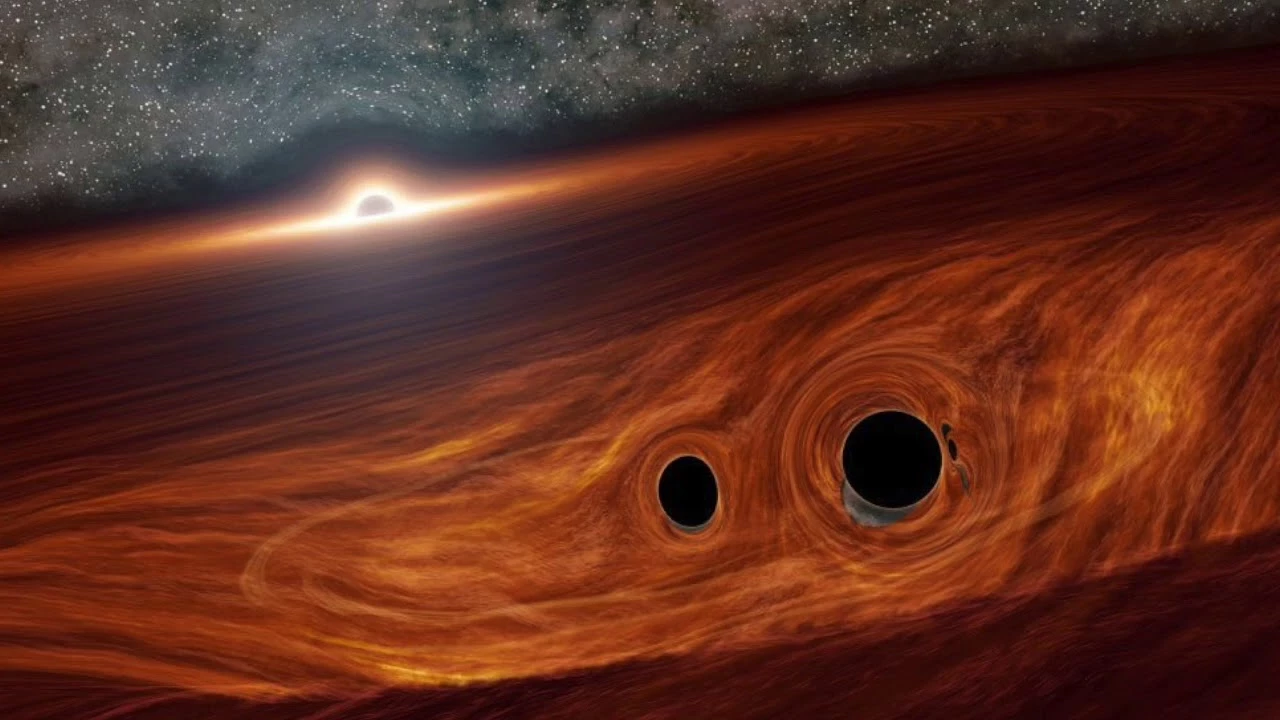

Instead, the team says it was most likely a merger between two smaller black holes caught in the disk of dust and gas around the supermassive black hole. The light flare wouldn’t come from the collision itself, but the dust and gas around it. After the two black holes become one, the resulting object would be shot off in a random direction, warping and heating the dust in its path.

"This supermassive black hole was burbling along for years before this more abrupt flare," says Matthew Graham, lead author of the study. "The flare occurred on the right timescale, and in the right location, to be coincident with the gravitational-wave event. In our study, we conclude that the flare is likely the result of a black hole merger, but we cannot completely rule out other possibilities.”

The true test for the black hole merger hypothesis could come in a few years’ time. According to their calculations, the collision should have sent the object flying on a trajectory that would send it back through the dusty disk, where it would produce another visible flare. Keeping an eye out for this in the next few years could confirm the idea.

The research was published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Source: City University of New York