The first results from ESA's Characterising Exoplanet Satellite (Cheops) exoplanet mission has revealed one of the hottest and most extreme planets orbiting another star. Located 322 light years away in the constellation of Libra, WASP-189 b is an ultra-hot Jupiter with a temperature so high that iron boils into a gas.

According to NASA, over 4,000 exoplanets have been discovered and confirmed, with many thousands more candidates awaiting confirmation. This has not only altered many of our ideas about the number of planetary systems in our galaxy, but also demonstrated that there are many very strange exoplanets out there.

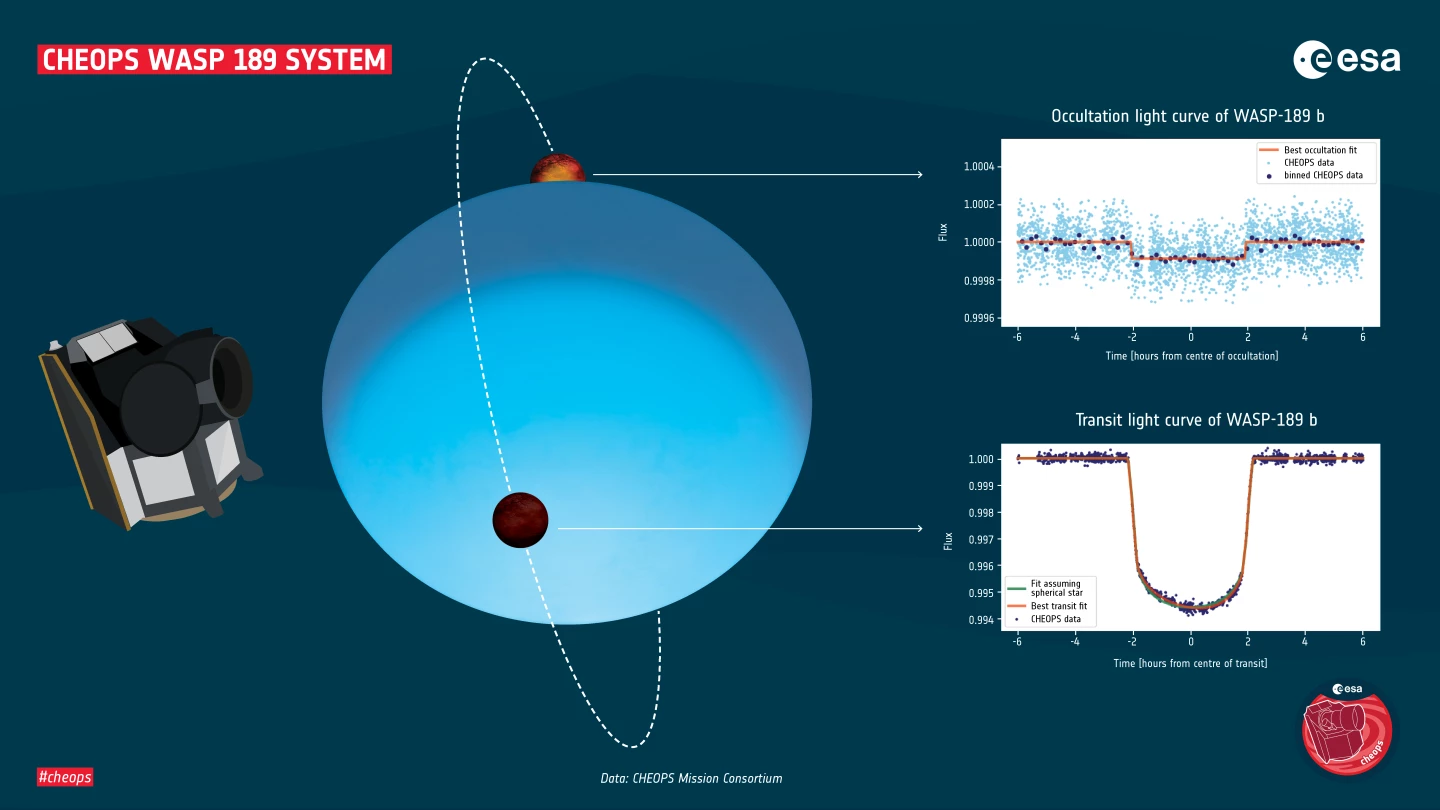

A case in point is Wasp-189 b, which was observed by Cheops when it began operations in January 2020. It used two methods to learn more about the planet's characteristics. The first, and most common tool used in exoplanet hunting and study, involved looking at how the light curve of a star dipped as the planet passed in front of it. To this, Cheops added analyzing the change in the light curve as the planet moved behind the star.

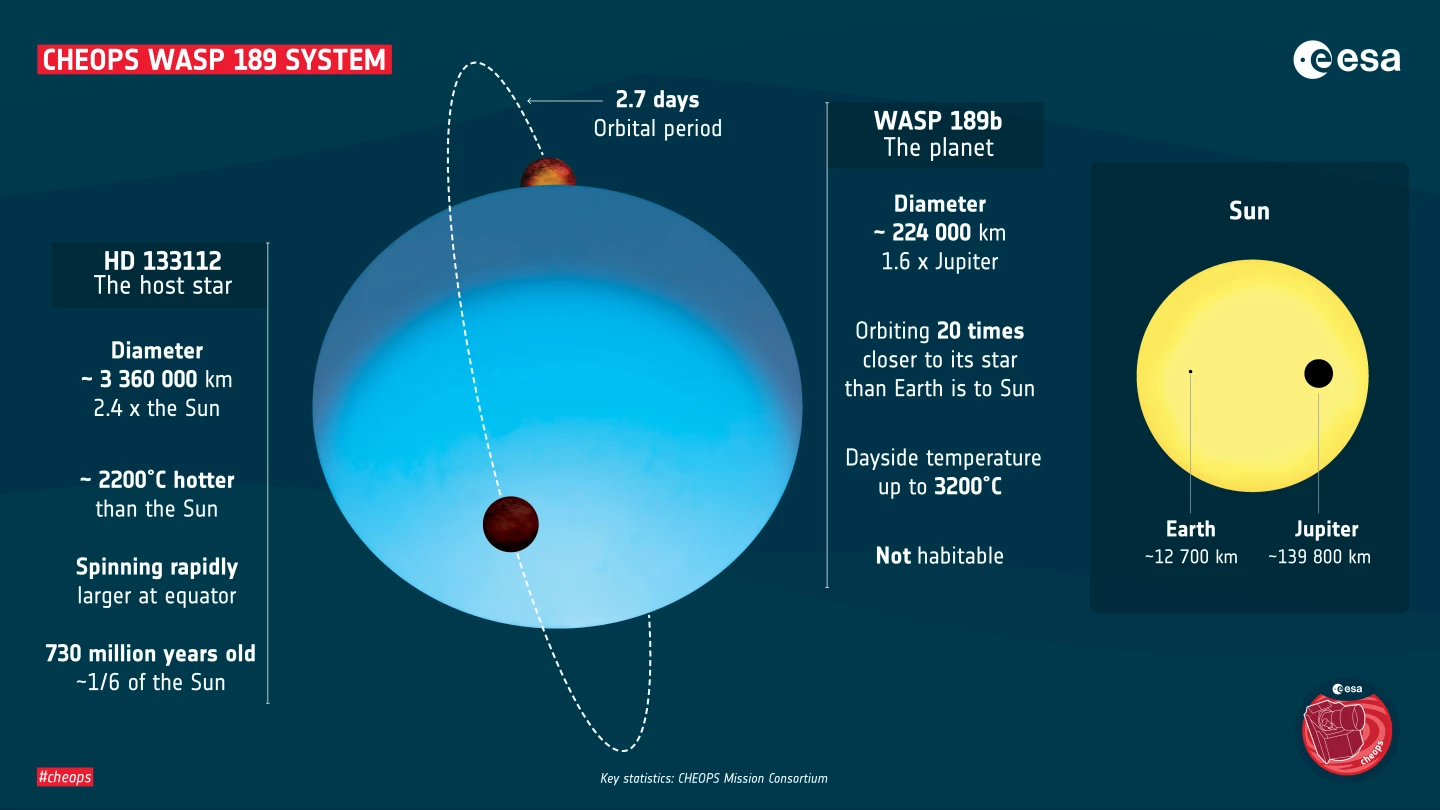

The combination of these two methods allowed scientists to deduce the size, shape, and orbital characteristics of Wasp-189 b. It turns out that the planet is 1.6 times the size of Jupiter and is 20 times closer to its star, which it orbits once every 2.7 days, than the Earth is to the Sun. The star, in turn, is a very young, very hot one that glows blue, is only 730 million years old, is 2.4 times wider than the Sun, and spins so fast that it is flattened at the poles.

The star is also 2,200 °C (3,960 °F) hotter than the Sun and the planet Wasp-189 b has a temperature of 3,200 °C (5,790 °F). By comparison, the boiling point of iron is 2,862 °C (5.184 °F), which means that metals like iron melt and become gas on the planet.

In addition to its high temperature, Wasp-189 b is also unusual in that it isn't orbiting close to its star's equator. Instead, it is at an angle that reaches almost to the poles. This suggests that the planet's orbit was altered by a close encounter with another planet or star, much in the same way that Jupiter influences the orbits of various bodies in the solar system.

"Cheops has a unique ‘follow-up’ role to play in studying such exoplanets," says Kate Isaak, Cheops project scientist at ESA. "It will search for transits of planets that have been discovered from the ground, and, where possible, will more precisely measure the sizes of planets already known to transit their host stars. By tracking exoplanets on their orbits with Cheops, we can make a first-step characterization of their atmospheres and determine the presence and properties of any clouds present."

The research was published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Source: ESA