NASA and DARPA have agreed to develop and test a nuclear rocket engine in space as soon as 2027. Using a nuclear reactor as its power source, it would outperform chemical rockets and greatly reduce the time for the first crewed Mars mission.

Humanity has made great strides in the exploration and exploitation of space over the past 60 years but as far as propulsion is concerned, the rockets of today are essentially the same as those of the German V-2 ballistic missiles of the Second World War. There have been innovations like solar sails and ion thrusters, but for manned missions or ones that must move very heavy payloads very quickly, the space agencies are still dependent on chemical-fueled rockets.

There are a number of problems with this, but the biggest one is that chemical rockets are operating at their theoretical limits. In fact, they had already come close to those limits by 1942. This means that crewed missions to the Moon can only be, at best, limited, expensive, and few, while a crewed Mars mission is at the very limit of the technology and could never be much more than a stunt.

To overcome this barrier, engineers are looking at more efficient and energy-dense propulsion based on nuclear reactor technology. NASA last made a serious attempt to develop a nuclear rocket in the 1960s with its Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application (NERVA) and Rover projects, but these were abandoned as the Apollo Moon-landing project began to wind down after 1964.

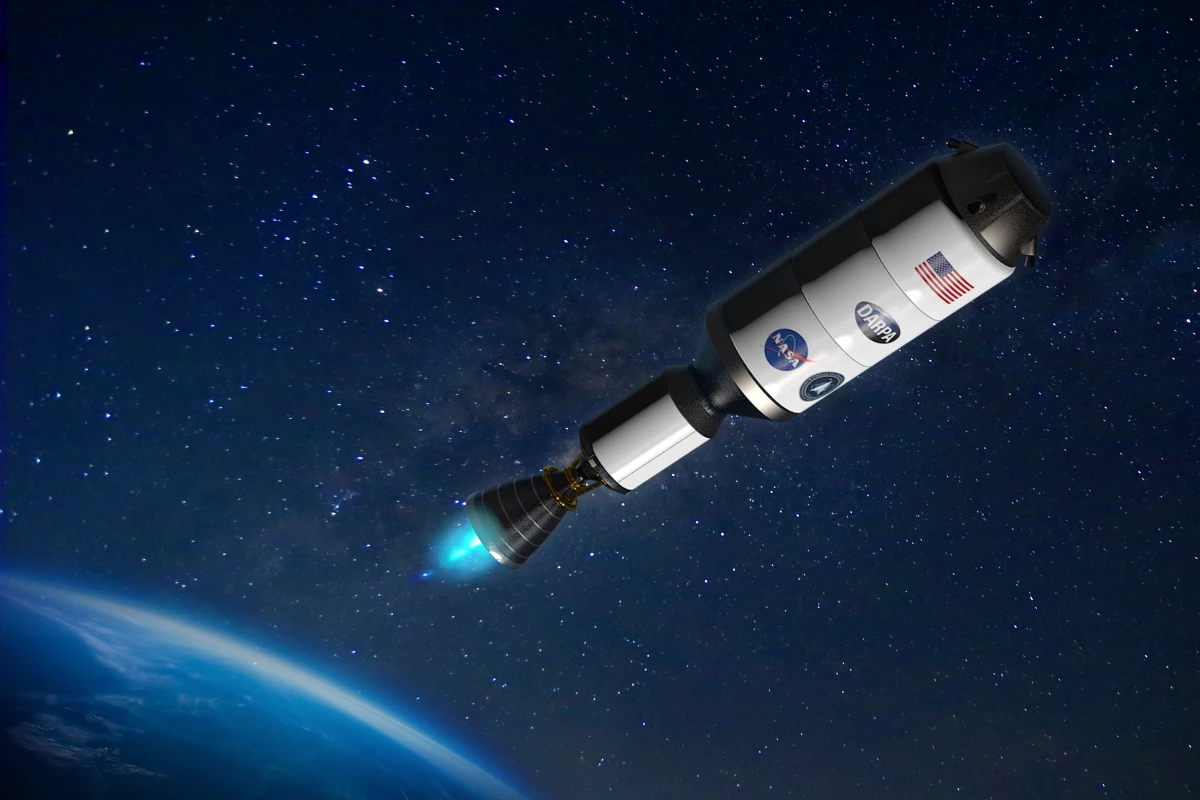

The latest endeavor is the Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations (DRACO) program, which is tasked with developing a nuclear propulsion system that is capable of sending a mission to Mars and also to provide the US Space Force with a means of getting to the Moon and moving about cislunar space with large payloads at very short notice.

By using a nuclear thermal engine to heat a propellant to extremely high temperatures to generate thrust, a rocket could have over three times the efficiency of a conventional chemical-fueled one, which would reduce transit times and increase payload potential. For a crewed Mars mission, this would mean less radiation exposure, fewer detrimental effects from weightlessness, and less of a need for supplies or overly robust flight systems.

In the new NASA/DARPA partnership, NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD) will lead development of the nuclear engine, which will be integrated into the DARPA spacecraft in the form of an upper stage that will only operate in space. Meanwhile, DARPA will continue as the contracting authority for the development of the entire stage, reactor, and the engine in anticipation of a first flight test in 2027 at the earliest – hopefully at a discreet distance from Earth.

"With this collaboration, we will leverage our expertise gained from many previous space nuclear power and propulsion projects," said Jim Reuter, associate administrator for STMD. "Recent aerospace materials and engineering advancements are enabling a new era for space nuclear technology, and this flight demonstration will be a major achievement toward establishing a space transportation capability for an Earth-Moon economy."

Source: NASA