Looking forward to the first manned Mars mission, ESA is delving into how astronaut hibernation would affect space missions. Based on sending six humans on a five-year mission to the Red Planet, the study suggests that using hibernation would allow the mass of the spacecraft to be reduced by a third, and the amount of consumables cut by roughly the same amount.

The idea of astronauts sleeping their way through a deep-space mission lasting months or years has been a staple plot device of science fiction since at least the 1930s and has featured in many movies as a way to speed up the story. Despite the chance of waking up to find one's self on a planet run by apes, it's an idea that is very attractive to real-life mission planners as a way to both reduce the supplies needed for lengthy missions and to keep the crew from going crazy.

The technology to actually make humans hibernate like bears or other mammals is still in its infancy, but that hasn't stopped ESA from looking at how hibernation could impact spacecraft designs and missions in general. Originally, studied as part of the space agency's Basic Activities research, hibernation is regarded as a key enabling technology and now ESA's Concurrent Design Facility (CDF), along with scientists from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and the University of Goethe, Frankfurt, are looking at the advantages that sleeping astronauts might bring to a Mars mission.

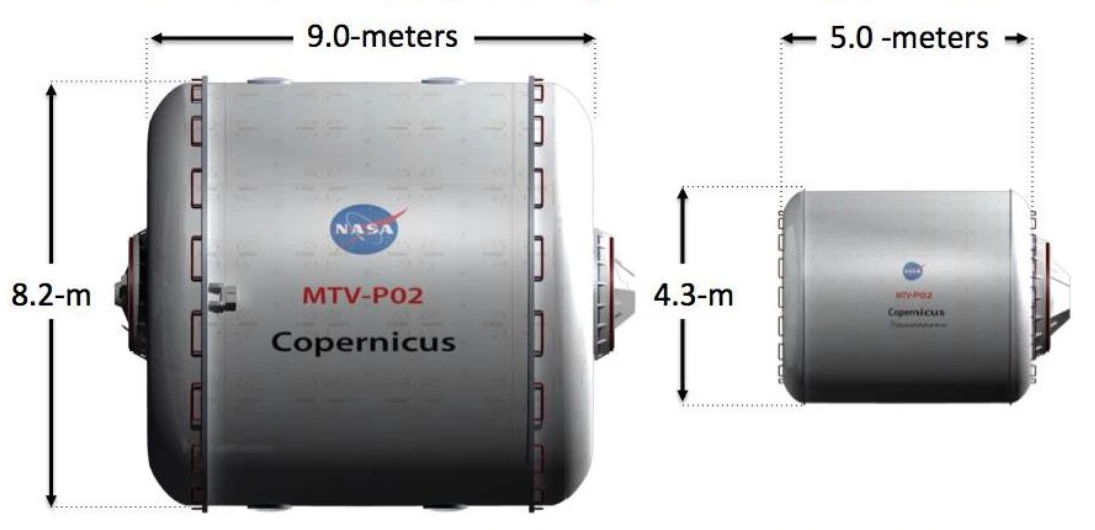

"We worked on adjusting the architecture of the spacecraft, its logistics, protection against radiation, power consumption and overall mission design," says Robin Biesbroek of the CDF. "We looked at how an astronaut team could be best put into hibernation, what to do in case of emergencies, how to handle human safety and even what impact hibernation would have on the psychology of the team. Finally, we created an initial sketch of the habitat architecture and created a roadmap to achieve a validated approach to hibernate humans to Mars within 20 years."

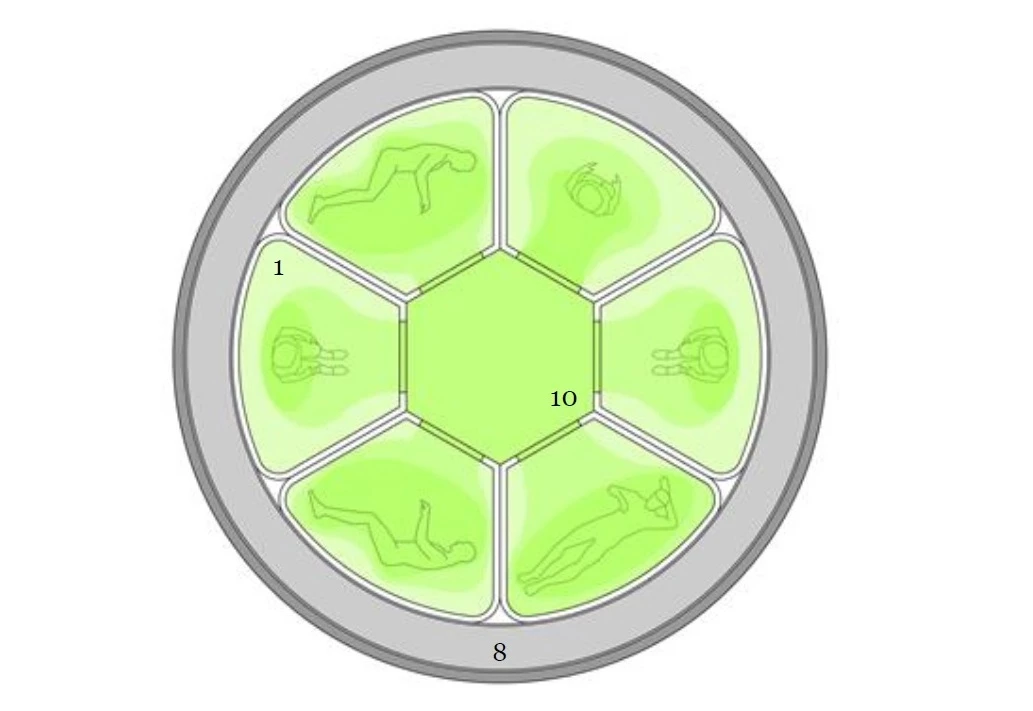

Hibernation would involve the astronauts bulking up like bears in the autumn in the run-up to the mission before being placed into individual sleeping pods on the craft that would double as living quarters after awakening. A still-hypothetical drug would induce the same state of torpor that many mammals enter naturally to sleep through winter and, like the animals, the astronauts would live off their extra body fat.

Meanwhile, the soft-shell pods would maintain a dark, cool environment to keep the crew in hibernation for the 180-day passage to and from Mars, followed by a 21-day recuperation phase. Though ESA says that the astronauts wouldn't experience bone or muscle loss, there would be a danger from cosmic radiation, so the quarters would need shielding from water tanks or other materials, but hibernation itself may provide some enhanced radiation protection in itself as evidenced by existing research.

In addition, while the crew is asleep, the craft would need a Hal 9000-like artificial intelligence to run the systems and conduct maintenance operations, so missions would need to be planned accordingly, with a focus on autonomous operations until crew members are revived.

"For a while now, hibernation has been proposed as a game-changing tool for human space travel," says SciSpacE Team Leader Jennifer Ngo-Anh. "If we were able to reduce an astronaut’s basic metabolic rate by 75 percent – similar to what we can observe in nature with large hibernating animals such as certain bears – we could end up with substantial mass and cost savings, making long-duration exploration missions more feasible.

"And the basic idea of putting astronauts into long-duration hibernation is actually not so crazy: a broadly comparable method has been tested and applied as therapy in critical care trauma patients and those due to undergo major surgeries for more than two decades. Most major medical centers have protocols for inducing hypothermia in patients to reduce their metabolism to basically gain time, keeping patients in a better shape than they otherwise would be.

"We aim to build on this in future, by researching the brain pathways that are activated or blocked during initiation of hibernation, starting with animals and proceeding to people."

Source: ESA