Flat-Earthers might have been right all along – they were just a few billion years late. Scientists at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) have found that newly formed planets might take on a flatter shape, before rounding out.

Planets are known to form out of protoplanetary discs – rings of dust and gas surrounding stars – but exactly how it happens is still up for debate. The most commonly accepted theory is called core accretion, where dust particles begin to stick together, forming larger and larger objects until they grow into planets. A less-favored but still plausible model, called disc instability, is thought to happen much faster, when the disc cools and collapses into lumps that then become planets.

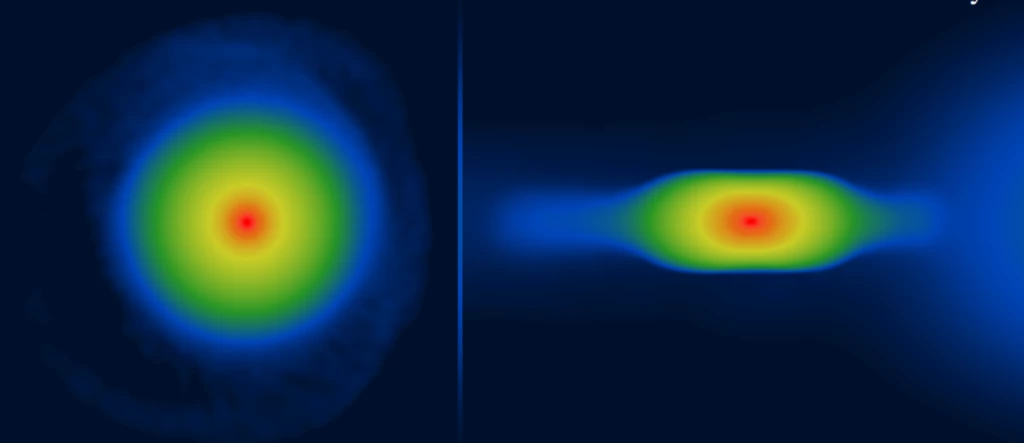

For the new study, the UCLan team ran supercomputer simulations of planet formation, with the goal of investigating an aspect that’s mostly been overlooked – what shape do young planets take?

“We have been studying planet formation for a long time but never before had we thought to check the shape of the planets as they form in the simulations,” said Dr. Dimitris Stamatellos, co-investigator on the study. “We had always assumed that they were spherical.”

Instead, the researchers found that when planets form through the disc instability method, they don’t grow outwards evenly, staying in a sphere shape the whole time – instead, they tend to gather more material at their poles than their equators, stretching them out into an “oblate spheroid,” which is kind of a flattened oval shape. As the young planets grow, they would of course eventually take on their familiar spherical form.

While these are just simulations so far, the team says that observations of young planets, to see if any do have this strange shape, could help confirm or rule out the disc instability method of planet formation.

The research has been accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics Letters (PDF).

Source: UCLan