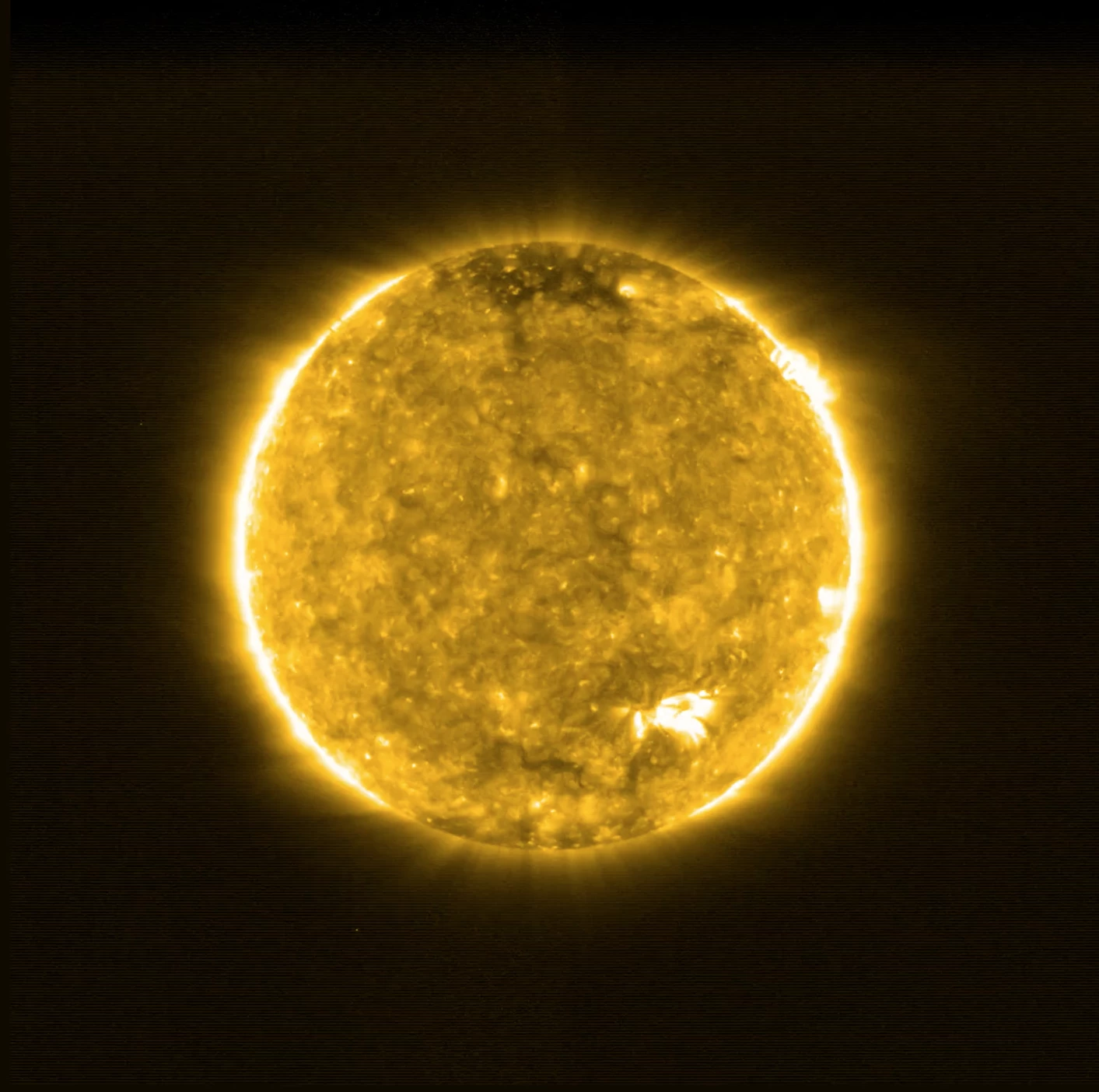

An ESA/NASA spacecraft has captured the closest pictures of the Sun ever taken, and revealed that our star is covered in relatively tiny flare-like explosions that scientists have dubbed "campfires." The stunning shots were taken by the Solar Orbiter spacecraft, as part of a collaborative mission that could revolutionize our understanding of the Sun.

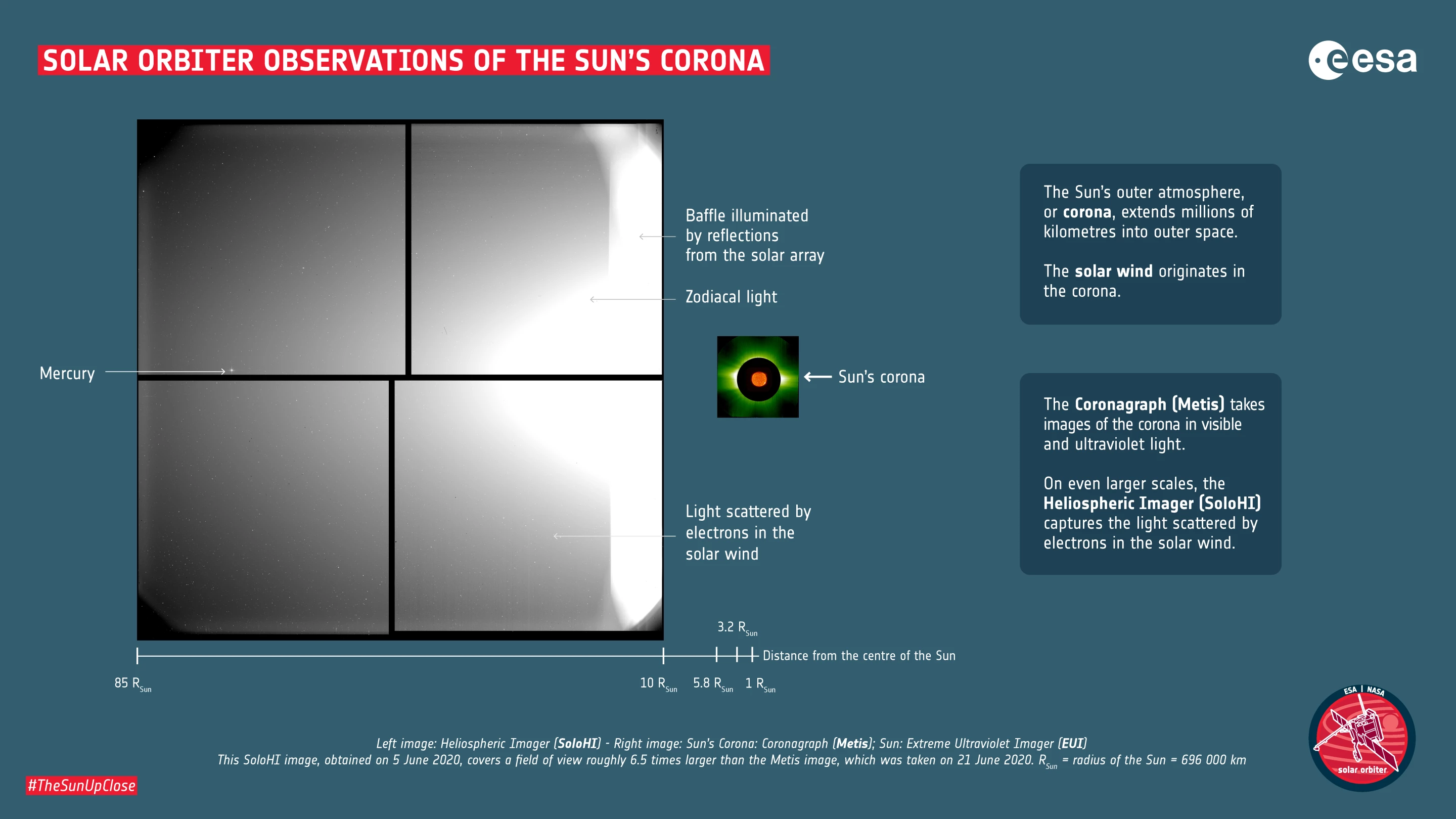

The Solar Orbiter was launched this year on the 10th of February, with a mission to unravel the secrets of Earth’s parent star using a suite of six scientific instruments. Among their number were six telescopes designed to image the Sun and its dynamic atmosphere, and four in situ instruments designed to monitor the characteristics of the space environment surrounding the probe.

Together, they will probe the origins of the solar wind that permeates throughout the heliosphere, and observe the complex processes occurring on and around our star. The spacecraft’s handlers have only just completed the commissioning stage of the mission – the point at which the instruments are validated for scientific use – and yet the Solar Orbiter is already making incredible discoveries.

"These are only the first images and we can already see interesting new phenomena," comments Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter Project Scientist. "We didn’t really expect such great results right from the start. We can also see how our 10 scientific instruments complement each other, providing a holistic picture of the Sun and the surrounding environment."

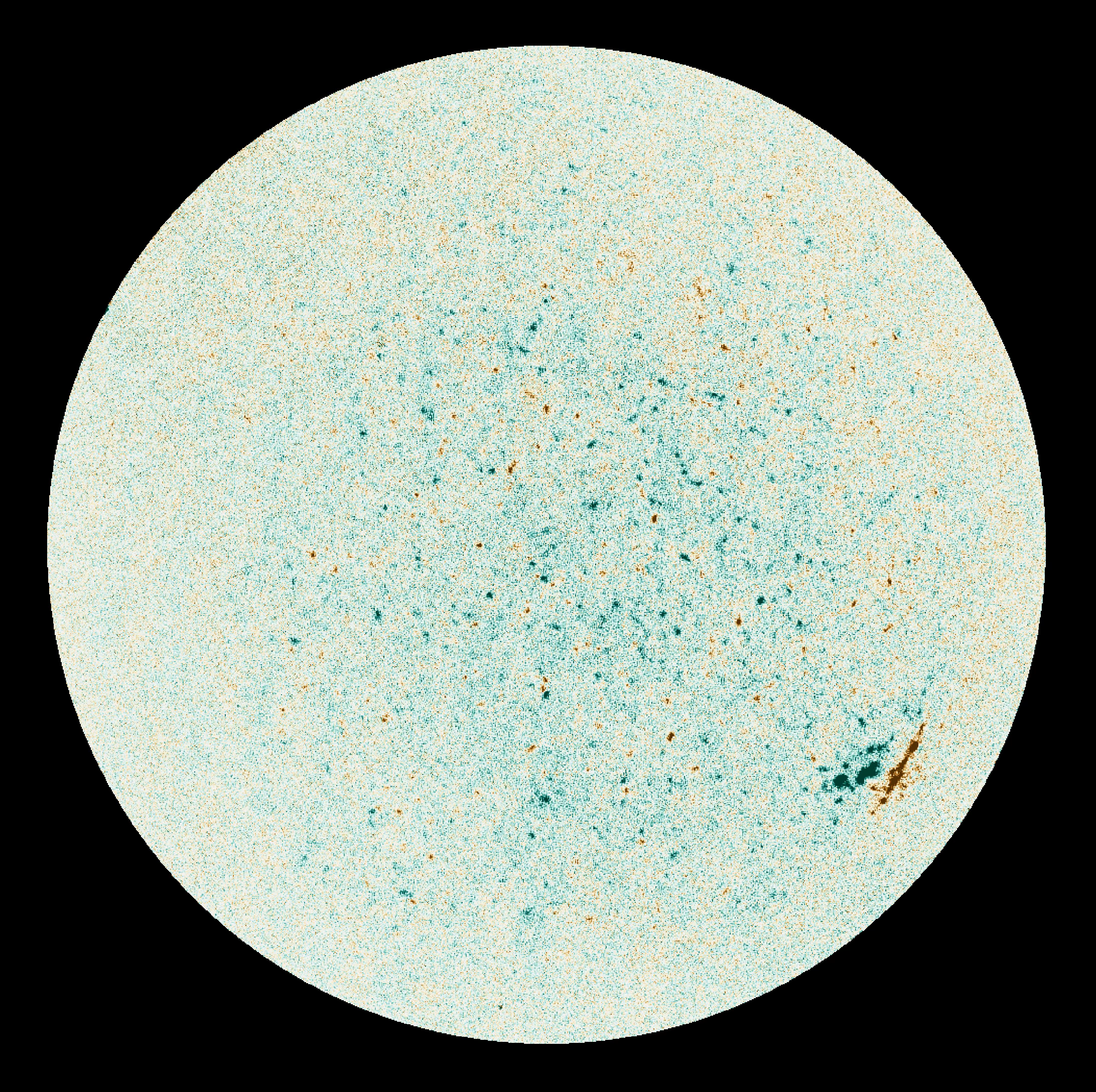

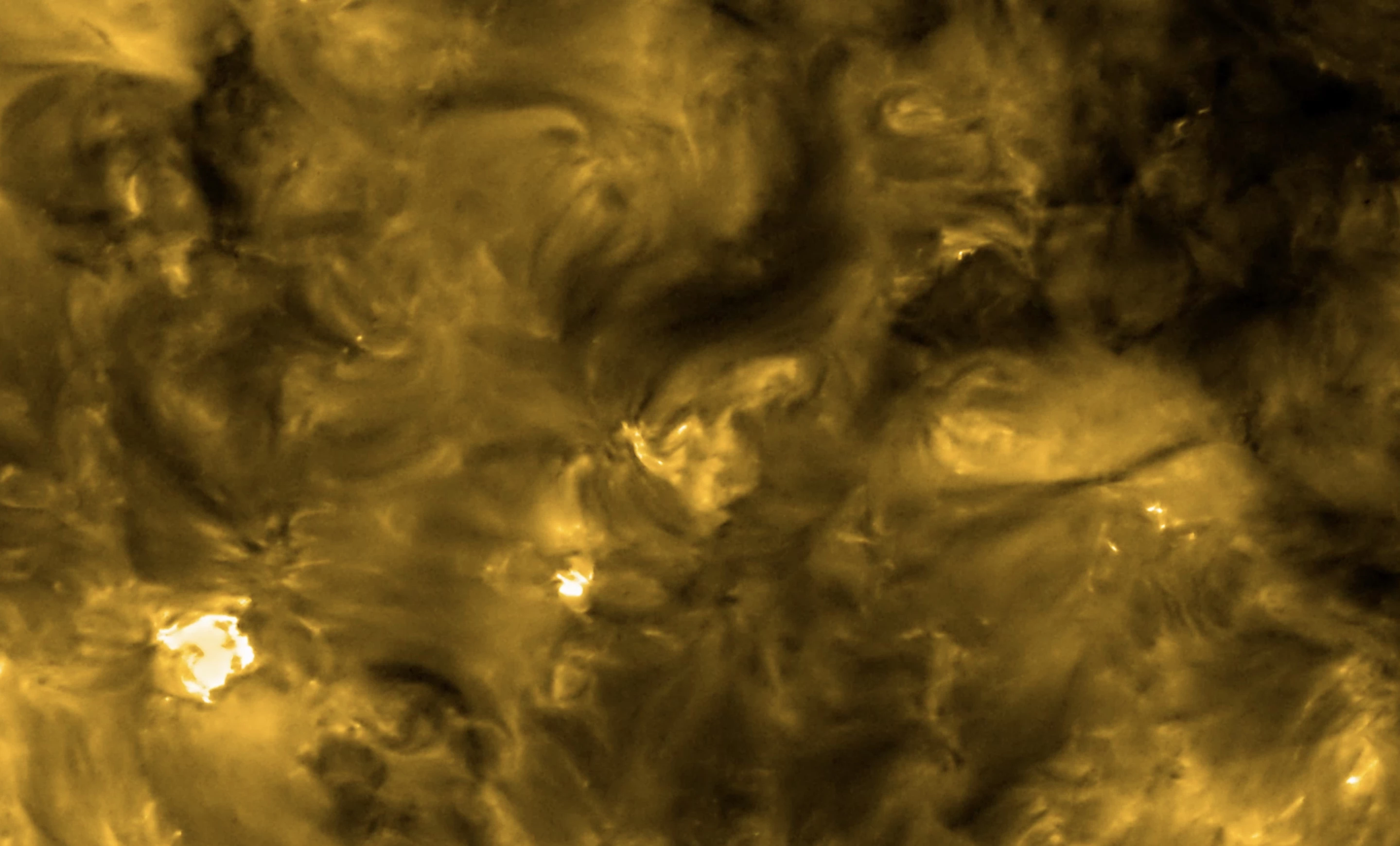

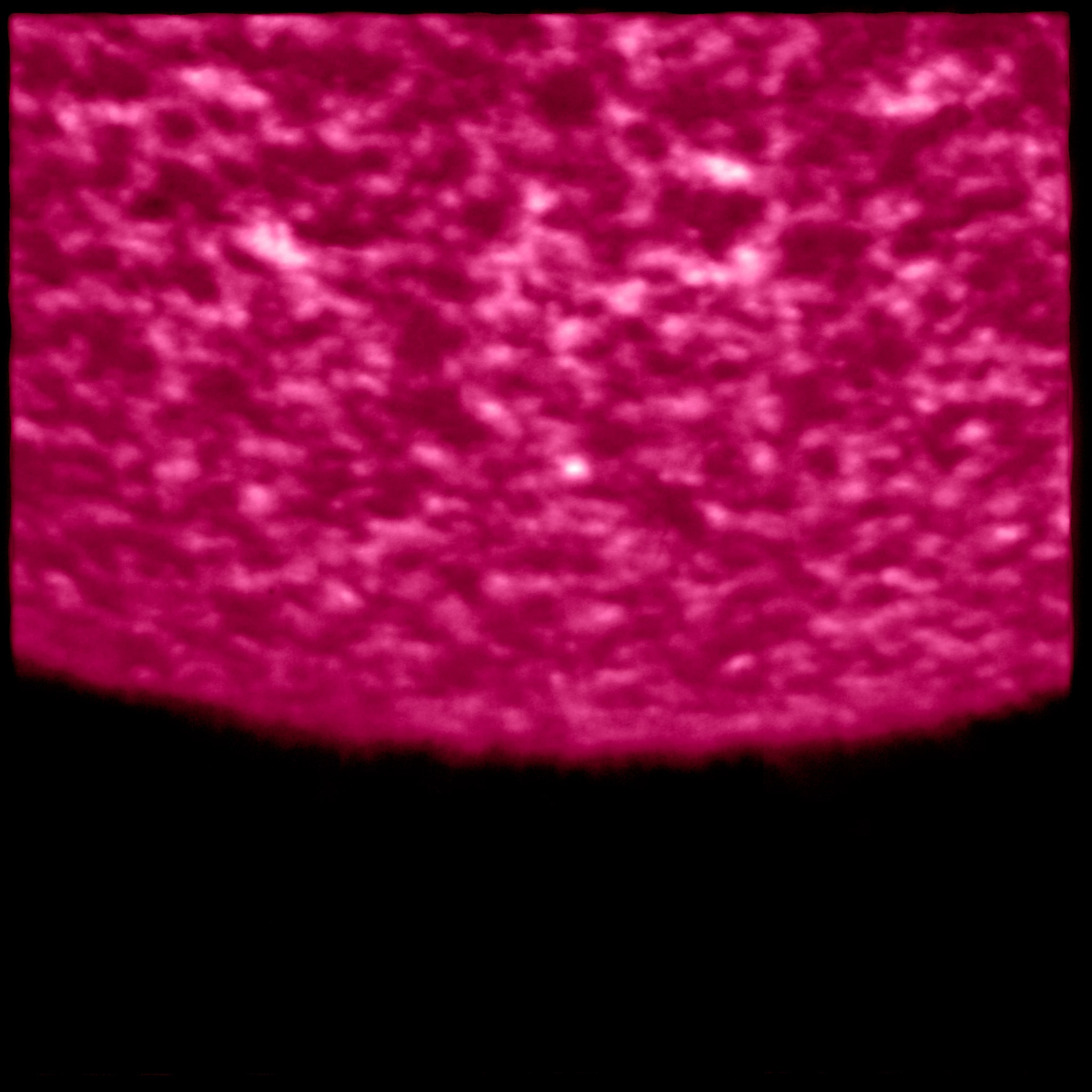

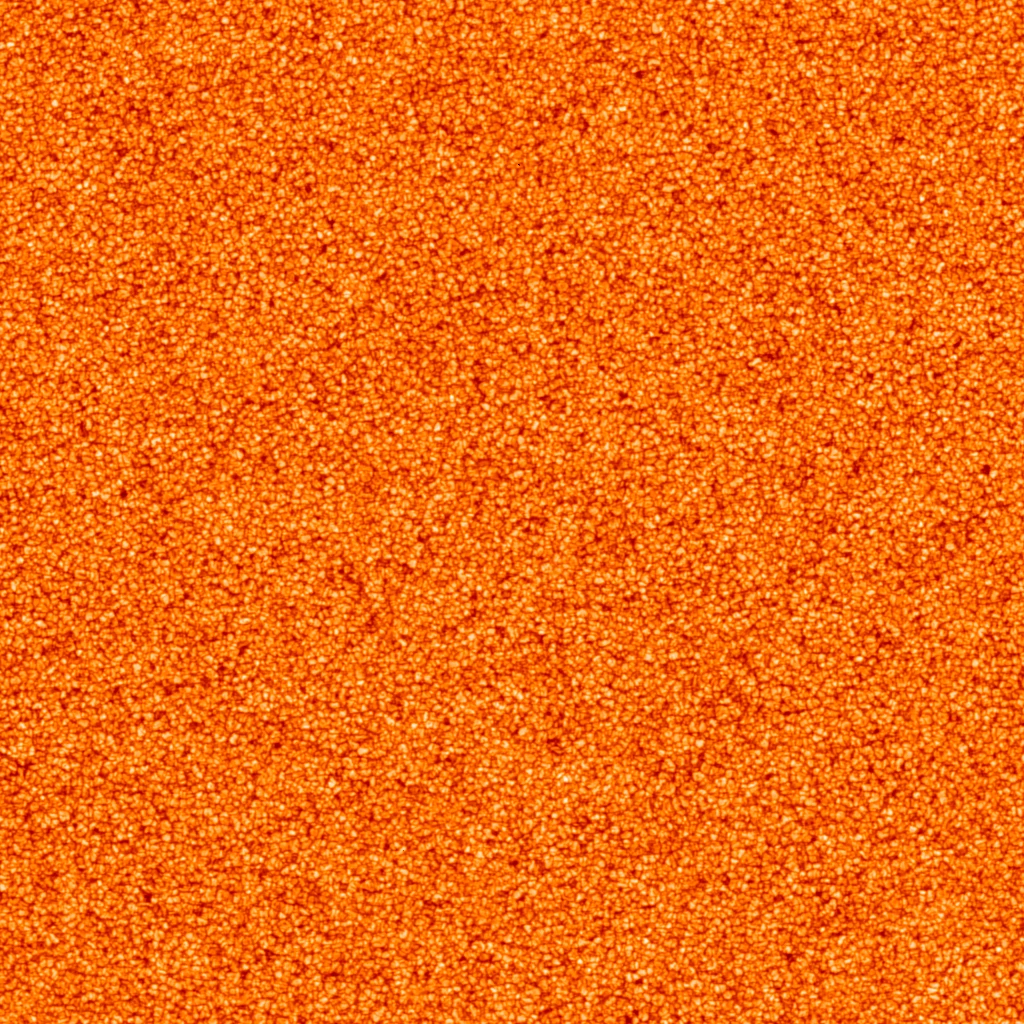

The first set of images captured by the probe’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) has revealed the presence of what scientists are calling "campfires" in the lower layers of the Sun’s super-hot atmosphere, also known as the corona.

"These unprecedented pictures of the Sun are the closest we have ever obtained," said Holly Gilbert, NASA project scientist for the mission at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "These amazing images will help scientists piece together the Sun’s atmospheric layers, which is important for understanding how it drives space weather near the Earth and throughout the solar system."

They could also shed light on a mystery surrounding the temperature of the corona. The visible surface of the Sun has a blistering temperature of 20,000 °F (11,093 °C). Logically, a person would assume that the atmosphere of the Sun would be somewhat cooler than the surface, but observations have shown that this is not the case. The corona is thought to have a temperature of over a million degrees Celsius, making it 200 to 500 times hotter than the surface of our star.

The counterintuitive nature of the corona has baffled scientists for decades. It’s the celestial equivalent to becoming far hotter when you step further away from a raging fire.

The new images were taken as the probe made its closest approach to the Sun in its current elliptical orbit, at a distance of around 48 million miles (77 million km). For context, the Earth orbits the Sun at an average distance of 93 million miles (149 million km). The images are the closest proximity shots ever taken of our star by a Sun-facing imager.

In the new images, the campfires appear as bright miniature eruptions, at least when seen from afar. In reality they are still mindbogglingly huge. It isn’t yet clear exactly what the campfires are. However, according to mission scientists, they appear to be the cousins of the larger solar flares that have been known to erupt from the Sun’s surface, and which have the potential to seriously disrupt modern-day technology on Earth.

As it stands, the scientific community is not sure as to the processes that trigger the appearance of these campfires. It’s possible that they are created in the same way that solar flares are formed – a process that involves the Sun’s magnetic field – albeit at a scale millions of times smaller. Alternatively they could be driven by an entirely new process currently unknown to science.

Some scientists believe that the campfires are helping to super heat the Sun’s corona.

"These campfires are totally insignificant each by themselves, but summing up their effect all over the Sun, they might be the dominant contribution to the heating of the solar corona," says Frédéric Auchère, of the Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale (IAS), France, Co-Principal Investigator of EUI.

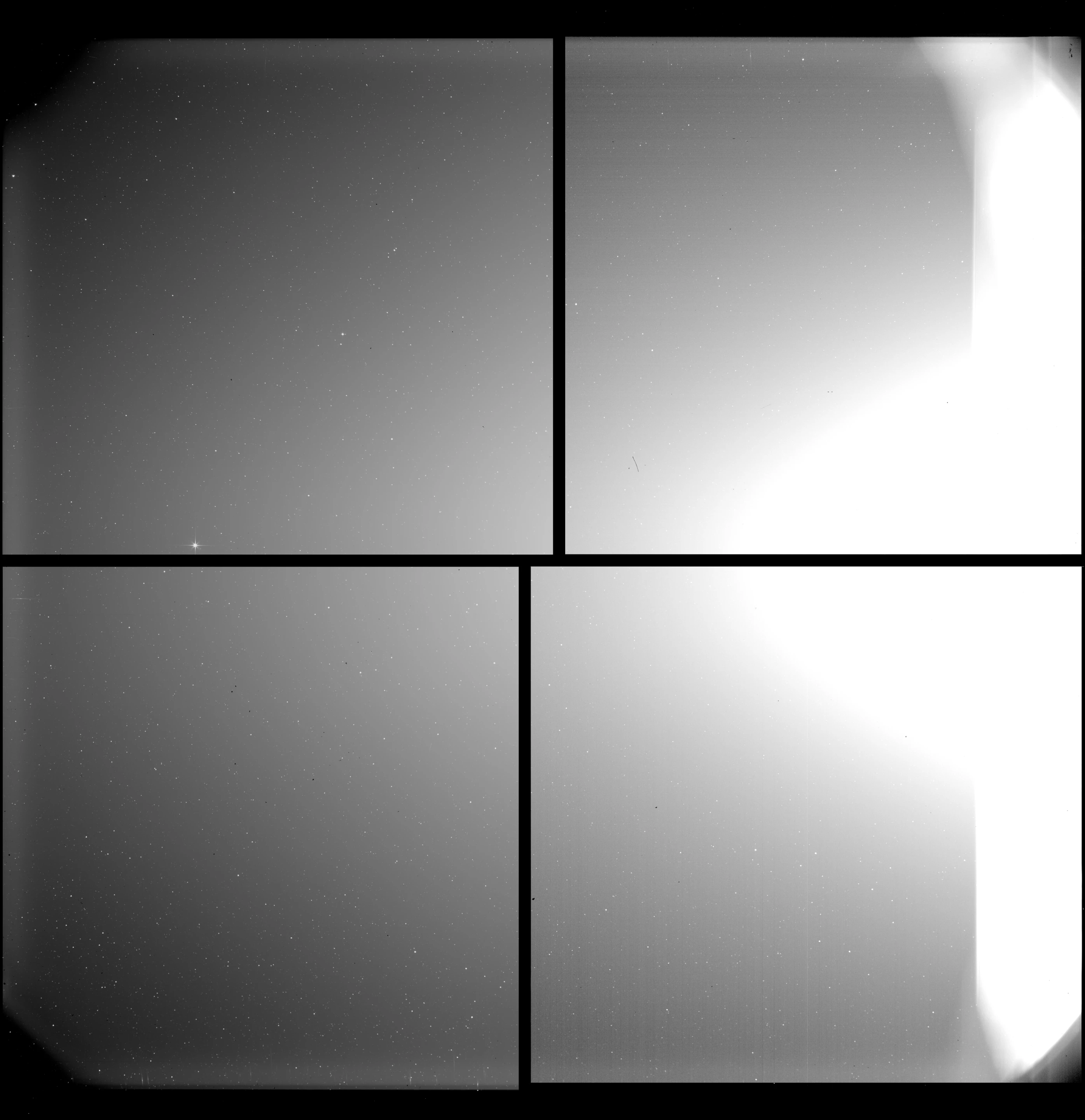

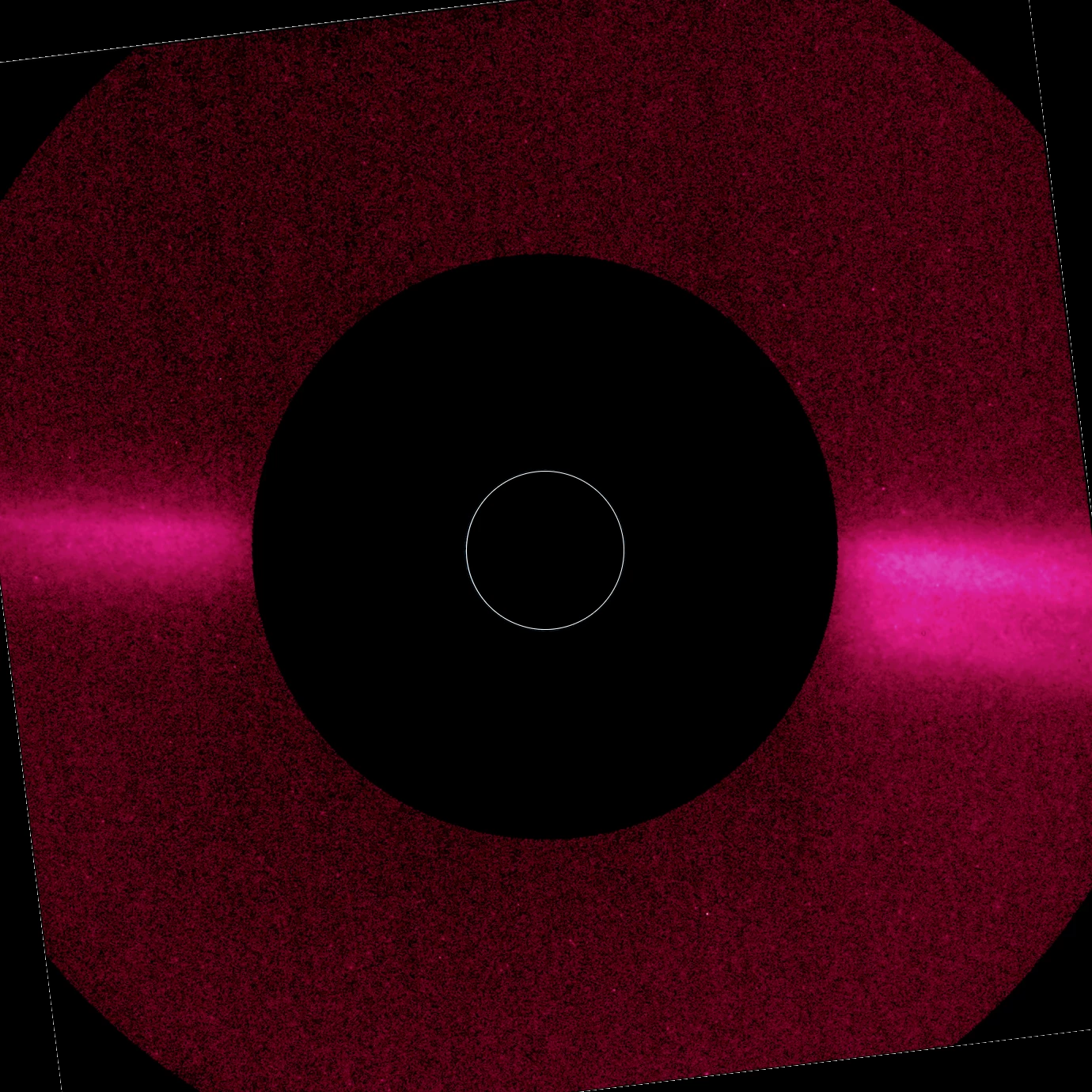

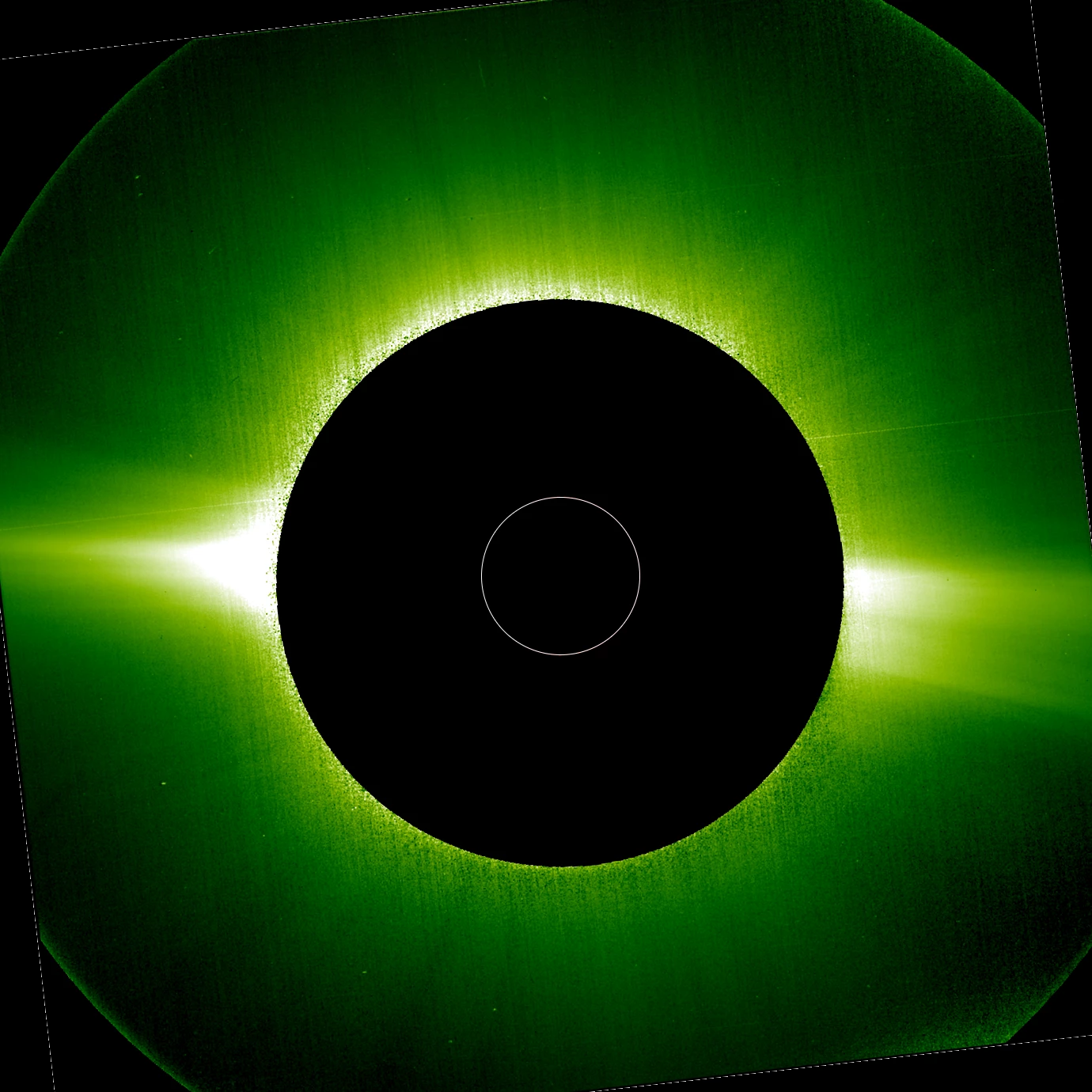

Another of the instruments busily taking measurements of the Sun during perihelion was the Polarimetric Helioseismic Imager (PHI). While the EUI took high-resolution images of structures in the solar atmosphere, the PHI was fervently collecting data on the magnetic field lines running across the surface of the Sun.

As a rule, regions boasting strong magnetic fields are more likely to birth a powerful solar flare, during which the Sun throws out vast quantities of energetic particles that feed into the solar wind.

"Right now, we are in the part of the 11-year solar cycle when the Sun is very quiet," says Sami Solanki, the director of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany, and PHI Principal Investigator. "But because Solar Orbiter is at a different angle to the Sun than Earth, we could actually see one active region that wasn’t observable from Earth. That is a first. We have never been able to measure the magnetic field at the back of the Sun."

Readings from the PHI detailing magnetic field strength across the Sun’s surface can then be compared to observations recorded by the four in situ instruments, which are keeping track of magnetic field lines and solar winds passing by the orbiter on its journey to the far reaches of the solar system.

By combining the data from multiple instruments, scientists can work out roughly where on the Sun the solar wind detected by the in situ instruments originated, and the conditions that gave rise to it.

"We are all really excited about these first images – but this is just the beginning," adds Daniel. "Solar Orbiter has started a grand tour of the inner Solar System, and will get much closer to the Sun within less than two years. Ultimately, it will get as close as 42 million km, which is almost a quarter of the distance from Sun to Earth."

The team is now waiting on data from the Solar Orbiter’s Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE), which will give precise measurements of the temperatures of the campfires. With this information it will be possible to estimate how much they contribute to the coronal heating phenomenon.

Other instruments aboard the probe will come into their prime later on in the mission, when the spacecraft shifts its orbit closer to the Sun.

Scroll down to watch a video highlighting the new images.