The James Webb Space Telescope has achieved one of the first major science goals announced for it way back in 2017. The infrared instrument has now probed the atmosphere around one of the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets.

Taking the reigns from the aging Hubble, James Webb is NASA’s latest flagship space telescope. Its huge mirror collects more light than anything before it to take high resolution images, while its infrared eyes allow it to peer much deeper in space and time. Altogether, the JWST is already proving invaluable in providing new insights into stars, planets, and the early history of the universe itself.

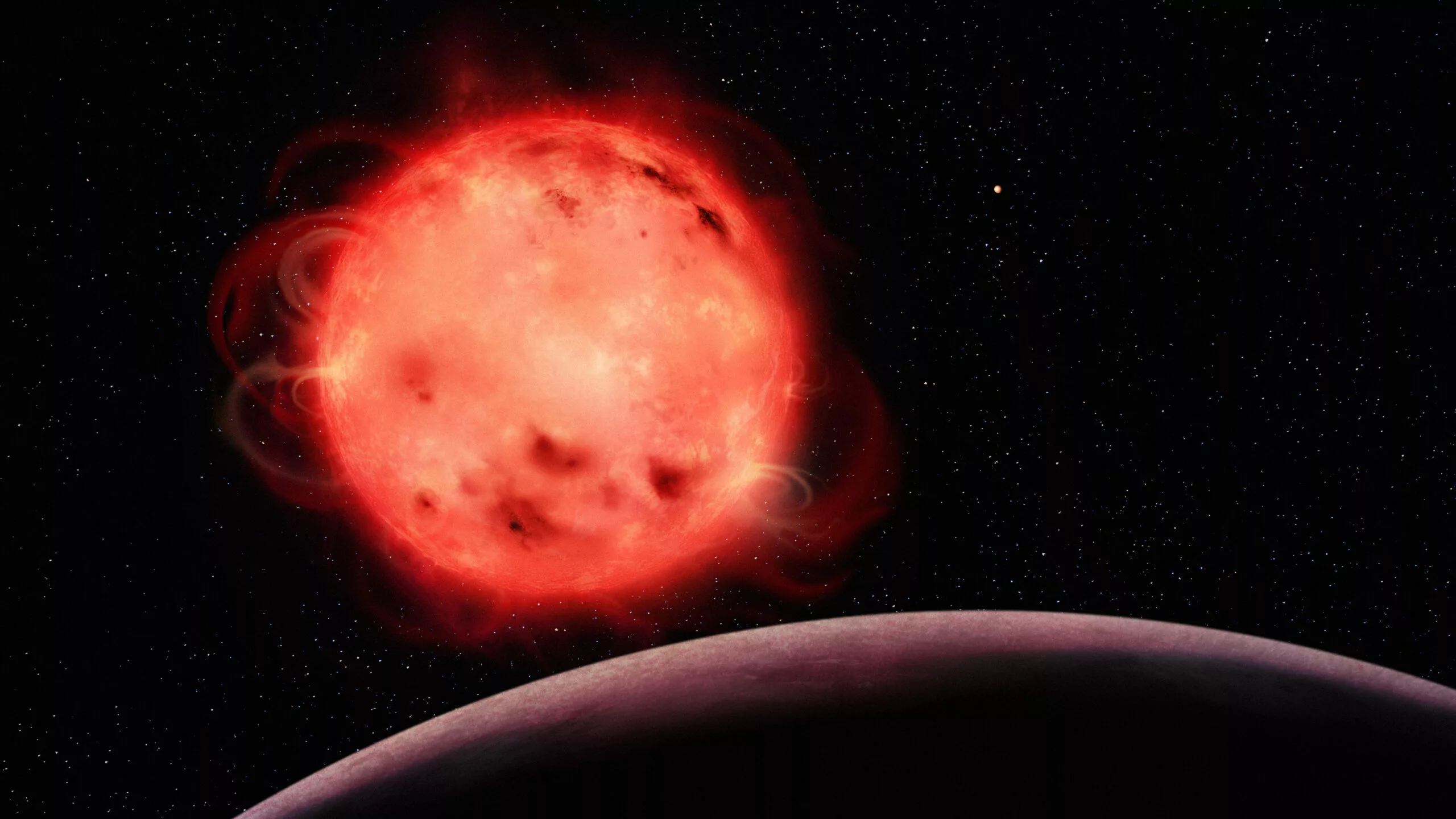

In 2017, astronomers discovered an extraordinary system of seven Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting a nearby red dwarf star known as TRAPPIST-1, a mere 40 light-years away. And naturally, scientists began to wonder what these entrancing exoplanets would look like through the yet-to-be-launched JWST’s eyes. Soon the system became one of the telescope’s first official science targets, with the goal of investigating the potential habitability of the planets.

And now, it’s taken its first glimpse of the atmosphere of the innermost world, TRAPPIST-1 b, using a method called transmission spectroscopy. When the planet passes in front of its host star, light streams through any atmosphere that’s present, blocking different wavelengths of light to different degrees, depending on the molecules in the air. This spectrum can then be analyzed to determine what the atmosphere is made up of, and from that other information can be gleaned such as whether the planet is habitable or not.

From this, the team found no sign that TRAPPIST-1 b has an atmosphere at all – its spectrum can be entirely attributed to the star’s activity alone. The finding is in line with other Webb observations made earlier this year that took the planet’s temperature and found an atmosphere unlikely. However, the possibility that it has a thin atmosphere composed of pure water, carbon dioxide or methane can’t be ruled out.

“Our observations did not see signs of an atmosphere around TRAPPIST-1 b,” said Ryan MacDonald, an author of the study. “This tells us the planet could be a bare rock, have clouds high in the atmosphere or have a very heavy molecule like carbon dioxide that makes the atmosphere too small to detect. But what we do see is that the star is absolutely the biggest effect dominating our observations, and this will do the exact same thing to other planets in the system.”

TRAPPIST-1 b was mostly a technological test for its more intriguing neighbors – TRAPPIST-1 d, e and f, which all orbit within the star’s habitable zone. The researchers say the study helped them learn how to account for the star’s hotter and colder spots, flares and other activity that can affect the atmospheric readings.

The research was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Source: University of Michigan