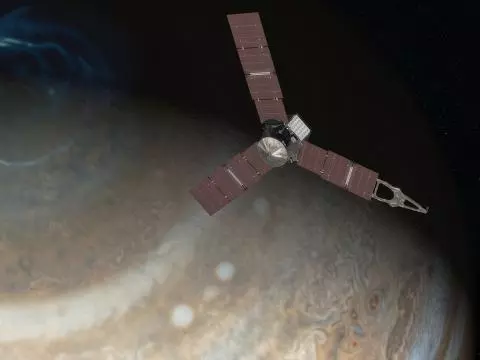

On December 30, 2023, NASA's Juno deep space probe made the closest flyby of Jupiter's moon Io in over two decades. The robotic spacecraft passed within 930 miles (1,500 km) of the volcanic satellite, returning closeup images of the south pole.

Launched on August 5, 2011, Juno is three years into its extended mission to study the giant planet Jupiter and its moons. Though the latest Io flyby is the closest for Juno, it is not the closest on record. That was achieved by the Galileo probe in 2001 when it sped by Io at a distance of 112 miles (181 km).

During Juno's flyby, the spacecraft's instrument recorded the remarkable volcanic activity on Io. The data returned by the three onboard cameras will help scientists to better understand the tidal forces that power such activity, and answer the question of whether a magma ocean exists beneath the volatile surface.

Even though Juno arrived at Jupiter in 2016, it's only completed 57 orbits of the planet. This is because the electronics onboard the probe, though heavily shielded, are easily damaged by Jupiter's tremendous radioactive belts. To minimize this, Juno spends most of its time a safe distance away and only makes periodic fast flybys to the inner Jovian system. Even then, the instruments onboard are already showing signs of seriously degrading, and Mission Control is constantly assessing them and developing workarounds.

According to NASA, the latest flyby has altered Juno's orbit from a period of 38 days to 35 days, and a second flyby scheduled for February 3rd will further reduce this to 33 days. This change in orbit will also increase the number of times Juno's solar panels are eclipsed by Jupiter. However, NASA engineers are confident that this will not leave the craft in darkness long enough to damage its systems.

"By combining data from this flyby with our previous observations, the Juno science team is studying how Io’s volcanoes vary," said Juno’s principal investigator, Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. "We are looking for how often they erupt, how bright and hot they are, how the shape of the lava flow changes, and how Io’s activity is connected to the flow of charged particles in Jupiter’s magnetosphere."

Source: NASA