A team of ESA scientists has developed a way to use lasers to accurately track space debris even in broad daylight. Using a combination of special telescopes, detectors, and light filters tuned to specific wavelengths, it's now possible to increase the contrast between sky and laser-illuminated objects enough to make the latter visible.

At any moment, there are 2,000 active and 3,000 inactive satellites orbiting the Earth and about one million bits of debris with a diameter of over a centimeter. Though the volume that they travel through is so large that the odds of a collision are small, with each bit of space junk hurtling around the Earth at hypersonic speed, a fleck of paint can still cause as much damage as a high-powered rifle bullet.

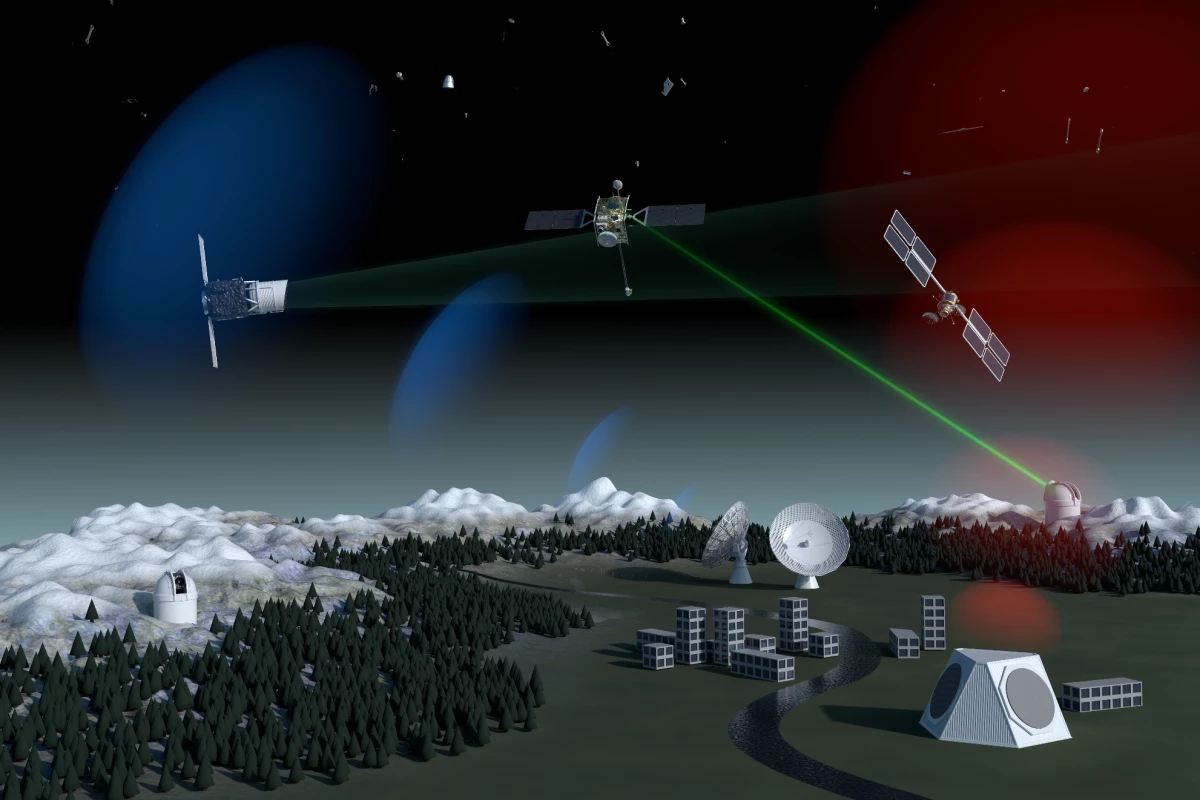

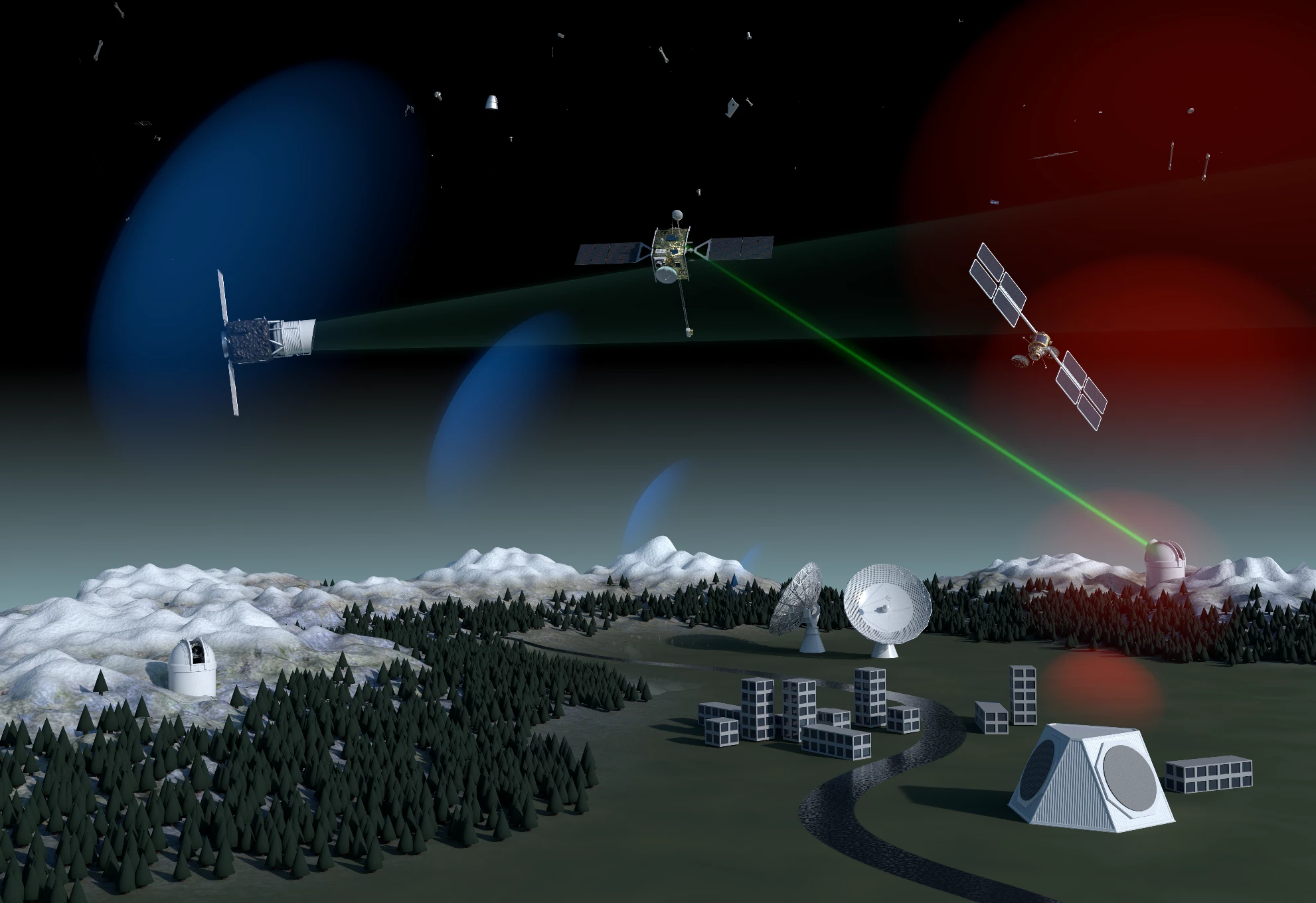

For these reasons, the space agencies of the world are very keen on mapping space debris in hopes of one day cleaning up the mess and, until then, avoiding damage to spacecraft. One way of doing this is by using satellite laser ranging (SLR) to pinpoint and track debris by measuring the time it takes for a light pulse to strike the satellites and return so that their trajectories can be predicted.

It's a technique that was first demonstrated in 1964 when the Beacon-B satellite was launched and then located to within a few meters a year later. Since then, the technology has advanced considerably and laser pulses lasting only picoseconds can track satellites to within millimeters.

Unfortunately, SLR needs a special reflector to bounce the laser back to the Earth station and most debris doesn't have anything like that, so trackers have to wait for a specific time to fire lasers at suspected debris. This is during the very few minutes as the debris circles the Earth when it is in the sunlight while the SLR station is in darkness. If the object went into the Earth's shadow or if it was daylight, tracking wasn't possible.

However, the new ESA SLR technique may change this. For daylight tracking, telescopes equipped with special light filters and photon detectors are able to shift the contrast of the day sky so much that satellites and even dim stars become visible. When a suspected debris fragment is above 15° in elevation, it's picked up by a 20-cm (7.9-in) tracking telescope mounted on the SLR telescope. By using special software, the SLR telescope can compensate for various biases and track the object by its reflected laser signature, gathering enough data for a precise orbital prediction.

So far, 40 debris objects and stars 10 times fainter than can be seen with the naked eye have been observed at midday.

"We are used to the idea that you can only see stars at night, and this has similarly been true for observing debris with telescopes, except with a much smaller time window to observe low-orbit objects," says Tim Flohrer, Head of ESA’s Space Debris Office. "Using this new technique, it will become possible to track previously 'invisible’ objects that had been lurking in the blue skies, which means we can work all day with laser ranging to support collision avoidance."

Details of the new technique were published in Nature Communications.

The video below shows the distribution of space debris in Earth orbit.

Source: ESA