Looking at data from NASA's Voyager 2 collected during the deep space probe's flyby of Uranus in January 1980, scientists have concluded that four of the planet's known 27 moons may have oceans beneath their icy crusts.

One of the more sensational discoveries from sending robotic probes to the outer planets of the solar system is that a number of the larger moons not only had crusts made of ice, but beneath their icy surfaces may be gigantic oceans encompassing the entire core of the satellites.

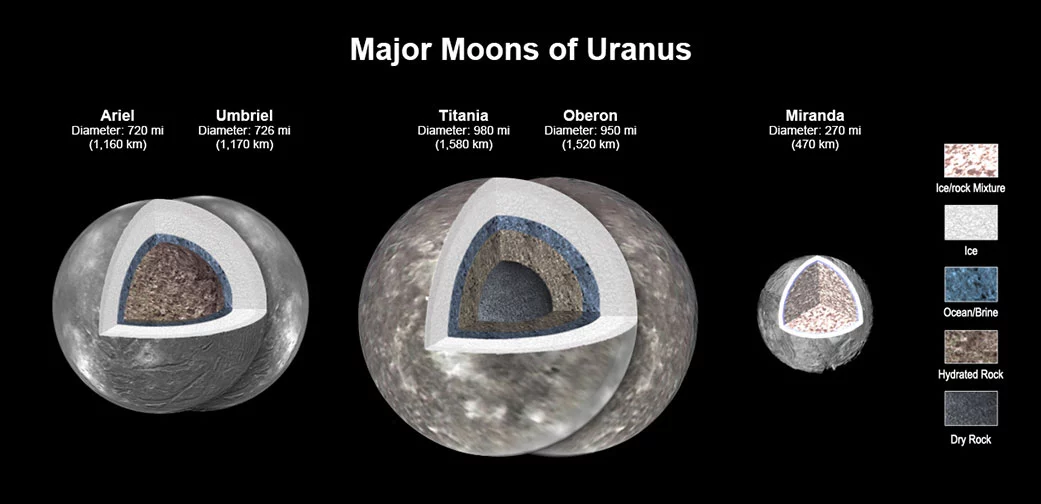

This was exciting enough when the moons of Jupiter and Saturn showed evidence of this. But the Voyager data indicates that Uranus' moons, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon, could have not just water but entire oceans.

In support of the National Academies’ 2023 Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey, the new NASA study is part of an effort to discover more about the solar system, and to provide criteria for planning future planetary missions.

In this case, the scientists used Voyager 2 data combined with ground observations from the 1980s to learn more about the structure of the larger Uranian moons.

According to NASA, it was already suspected that the largest moon, Titania, with its diameter of 980 miles (1,580 kilometers) might be large enough to retain enough heat generated by the decay of radioactive elements for liquid water. But the other three moons were thought to be too small.

To test this, the team built computer models that included findings from NASA's Galileo, Cassini, Dawn, and New Horizons missions that sent back data about the chemistry and geology of Saturn’s moon Enceladus, Pluto and its moon Charon, and Ceres.

By looking at how porous the Uranian moons' outer crusts are, the study showed that they provide ample insulation to retain interior heat being released from the moons' rocky mantles – enough to support oceans. In fact, Titania and Oberon's oceans might be warm enough to support life. Of the five largest moons, only Miranda was viewed to be too small to retain the heat needed to prevent a body of water from freezing.

In addition to the heat equation, these oceans may owe their existence to the presence of ammonia and other chlorides that act as antifreeze. This knowledge also helps mission planners to develop spectrometers to study the moons, as well as instruments that can detect electrical currents that might contribute to the moon's magnetic field.

"When it comes to small bodies – dwarf planets and moons – planetary scientists previously have found evidence of oceans in several unlikely places, including the dwarf planets Ceres and Pluto, and Saturn’s moon Mimas," said Julie Castillo-Rogez of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "So there are mechanisms at play that we don’t fully understand. This [research] investigates what those could be and how they are relevant to the many bodies in the solar system that could be rich in water but have limited internal heat."

The study was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

Source: NASA