NASA has released the first significant findings from the Parker Solar Probe's first two close encounters with the Sun that began in November 2018. In four new study papers, mission scientists outline how the spacecraft passing closer to the Sun than any previous mission has both confirmed theories and sprung a few surprises.

When the Parker Solar Probe plunged to within 15 million mi (24 million km) of the Sun, it was more than a technological challenge to see if a spacecraft could survive the fiery ordeal. It was also a way to learn things about the Sun that are only visible up close and personal.

The real challenge is that many phenomena associated with the Sun are surprisingly complex, small-scale, and invisible against the Sun's glare of light and radiation from any real distance. That's the reason why Parker was sent well within the orbit of Mercury – to place a suite of instruments close enough to gather data as the probe's eccentric orbit sends it on its increasingly closer solar flybys.

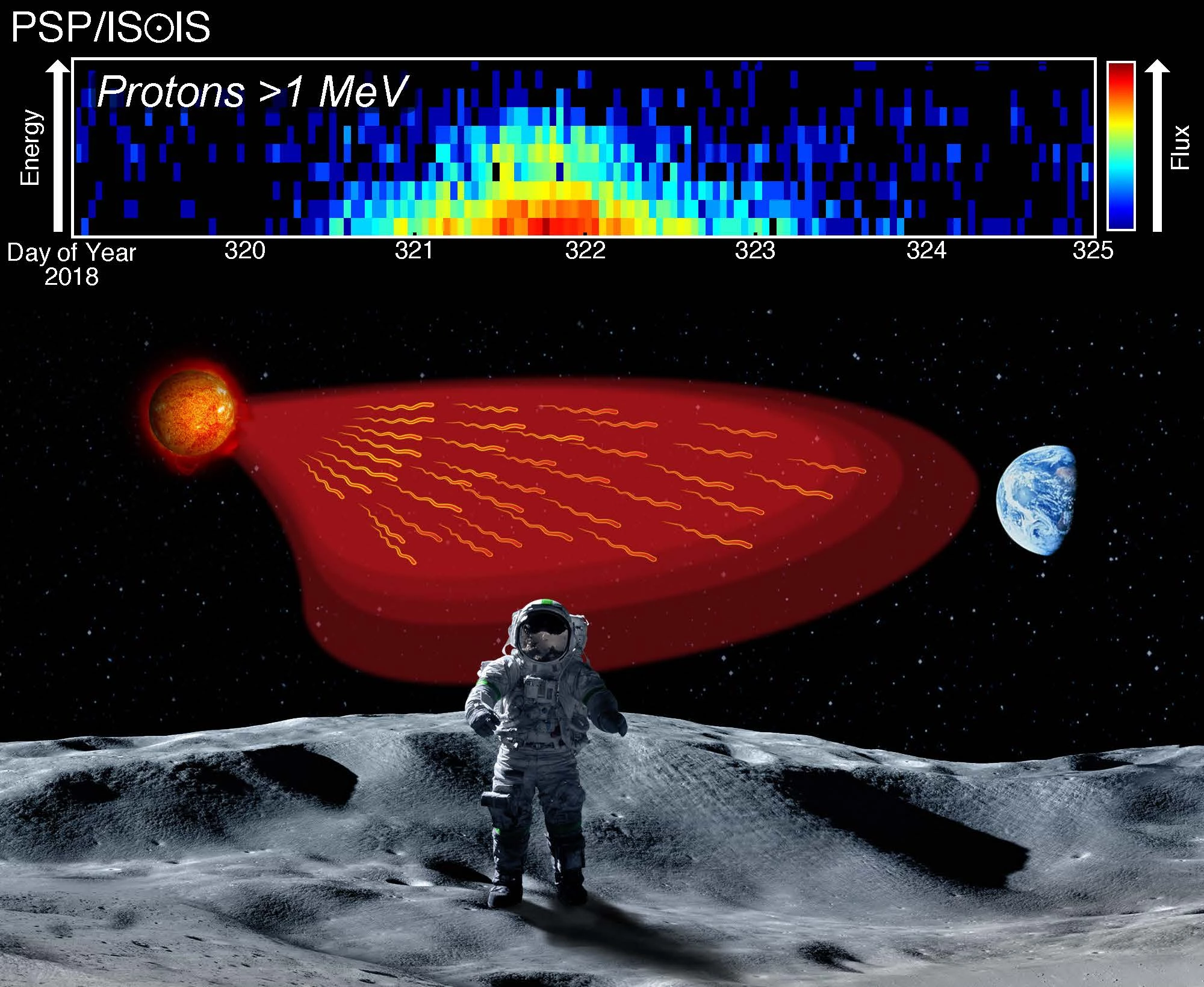

In four new papers, space scientists reveal how data from Parker provides new insights into the Sun's activity, which will help in predicting space weather – especially solar flares, which pose a real hazard to astronauts, satellites, communications, and even earthbound power grids.

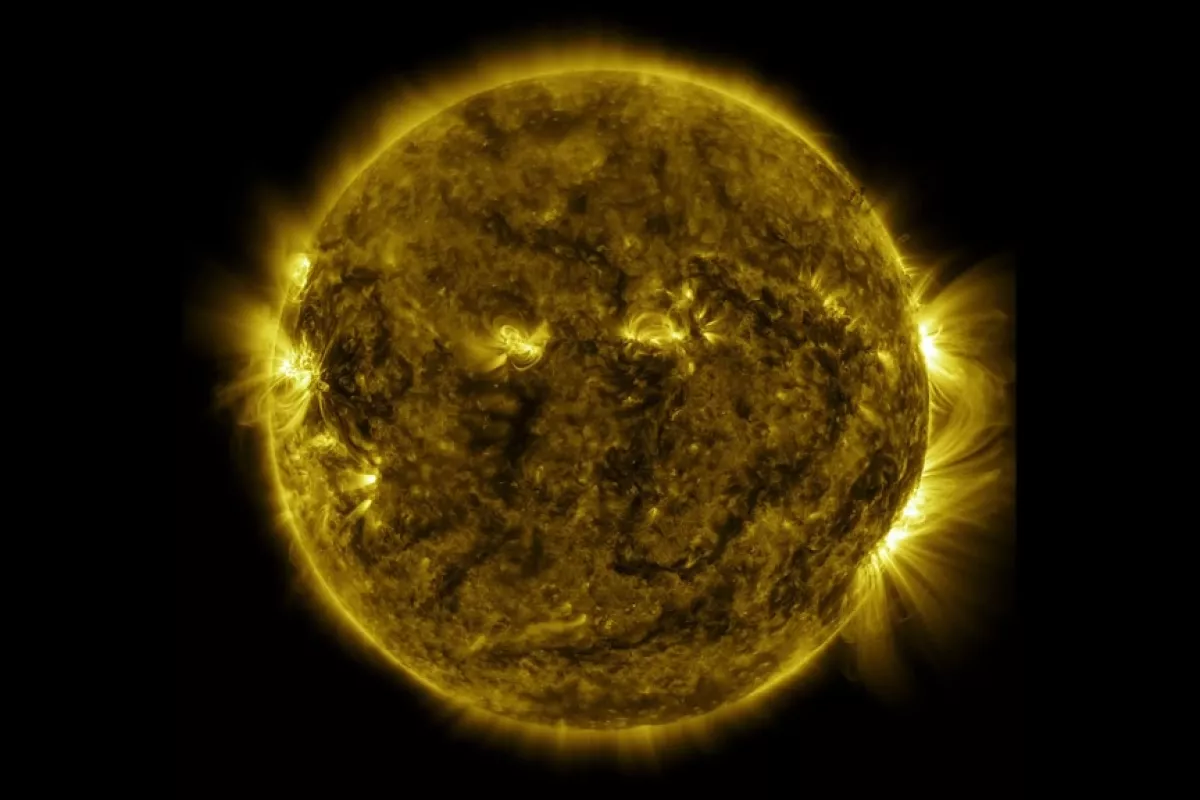

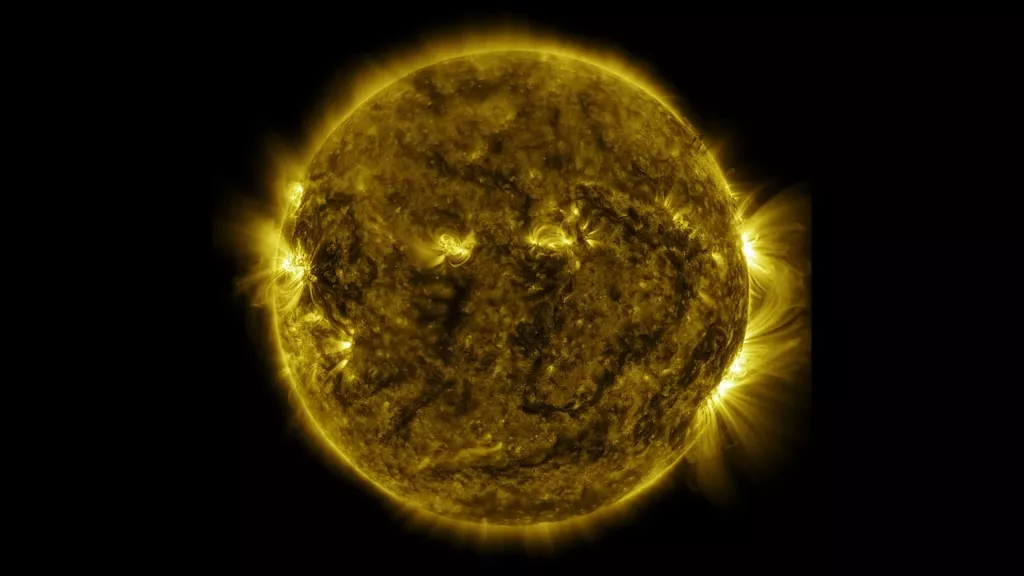

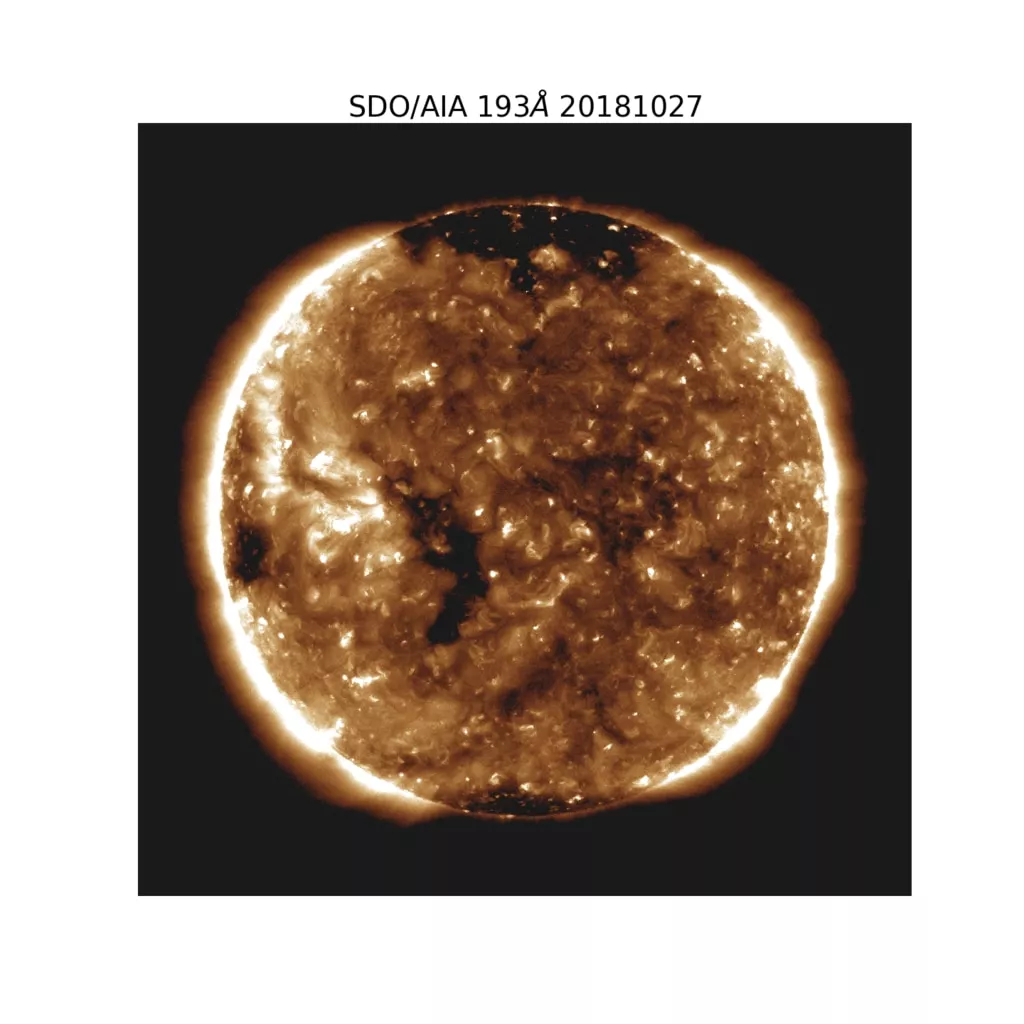

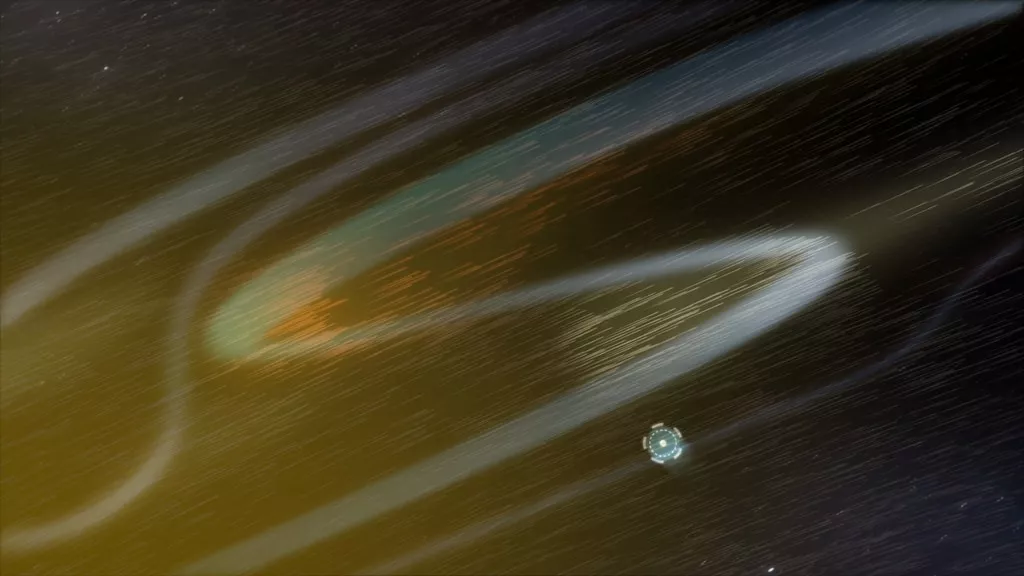

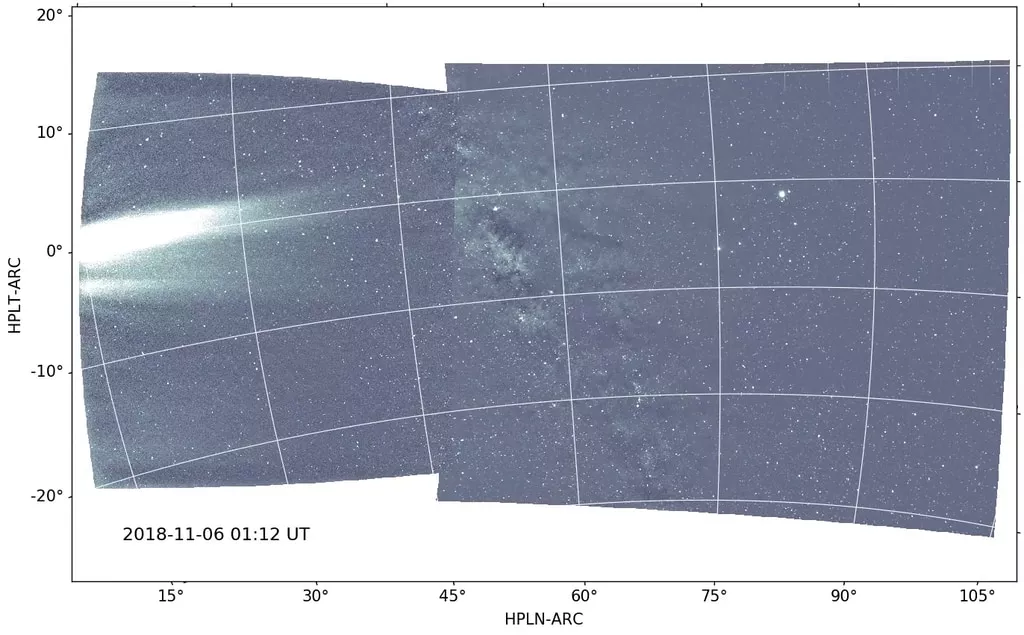

Every second of every day, the Sun spews out 1.9 million tonnes of material. As seen from Earth, this constantly blowing solar wind seems homogeneous and featureless, but Parker has shown that it's actually a dynamic and highly structured system that NASA compares to an estuary where a river meets the sea.

The first phenomenon that Parker has cast new light on is solar "switchbacks," which is the tendency of the magnetic field inside the orbit of Mercury to flip its direction every few seconds to a few minutes. These flips haven't been detected farther out from the Sun and could only be seen by Parker as it passed through the close-in magnetic field. According to NASA, these switchbacks can not only help in learning more about space weather but also in gaining a better understanding of how stars release magnetic energy.

Another Parker finding was how the rotation of the Sun affects the solar wind. From Earth's point of view, the wind comes from the Sun in straight spokes, but because the Sun is spinning, this rotation should have an impact on the wind as it is generated. As the probe came within 20 million mi (32 million km) of the Sun, it found that the wind was shifted sideways more, faster than expected, indicating that the interaction of the Sun and its corona is affecting the former's rotation, which could influence its life cycle.

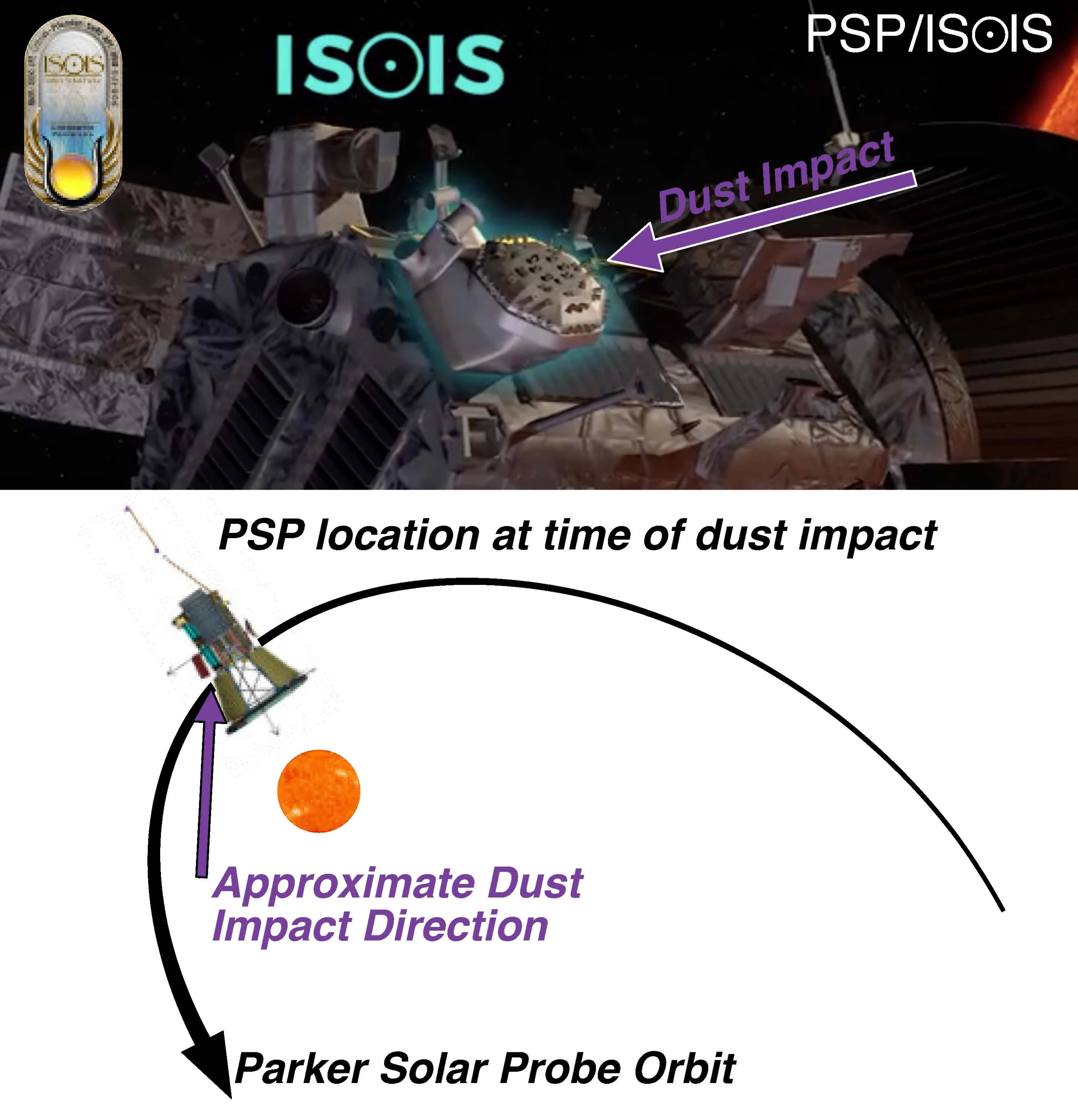

The third finding is that there isn't a lot of dust in close proximity to the Sun. This has been suspected for about a century, but Parker is the first time that it's been seen directly. At the rate of thinning seen by the probe, scientists calculate that anywhere within about three million mi (five million km) of the Sun may be dust-free – something the Parker probe will be able to confirm during its sixth flyby in September 2020.

The fourth major discovery to date comes from Parker's Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun (ISʘIS) energetic particle instruments. These have seen energetic particles from the Sun interact on a small scale that has never been encountered before and involved a high ratio of heavier elements. NASA says that a better understanding of these interactions is important because their sudden onset results in potentially harmful space weather conditions near Earth.

"This first data from Parker reveals our star, the Sun, in new and surprising ways," says Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for science at NASA. "Observing the Sun up close rather than from a much greater distance is giving us an unprecedented view into important solar phenomena and how they affect us on Earth and gives us new insights relevant to the understanding of active stars across galaxies. It’s just the beginning of an incredibly exciting time for heliophysics with Parker at the vanguard of new discoveries."

The research was published in Nature.

Source: NASA