Using the thermal equivalent of giving it a sharp whack, NASA repaired the camera of its Jupiter-orbiting Juno probe from 370 million miles (590 million km) away after the instrument was put out of commission by the gas giant's radiation belts.

If there's one thing that NASA has learned over the last 67 years it's the sort of on-the-fly innovation that one normally associates with an old MacGyver episode. Time and again the space agency's engineers have found themselves hundreds, thousands, millions, and even billions of miles away from some technical problem that they have to solve with nothing more than a radio command as a tool.

Sometimes, this can be as simple as getting a stuck solar panel on a satellite to deploy. Other times it's talking a trio of astronauts through the repair of the life support on their crippled Moon ship using hoses and duct tape so they can get home alive. Now a NASA team has been called upon to fix a camera that should have been tossed in the bin, except the nearest trash receptacle was back on Earth.

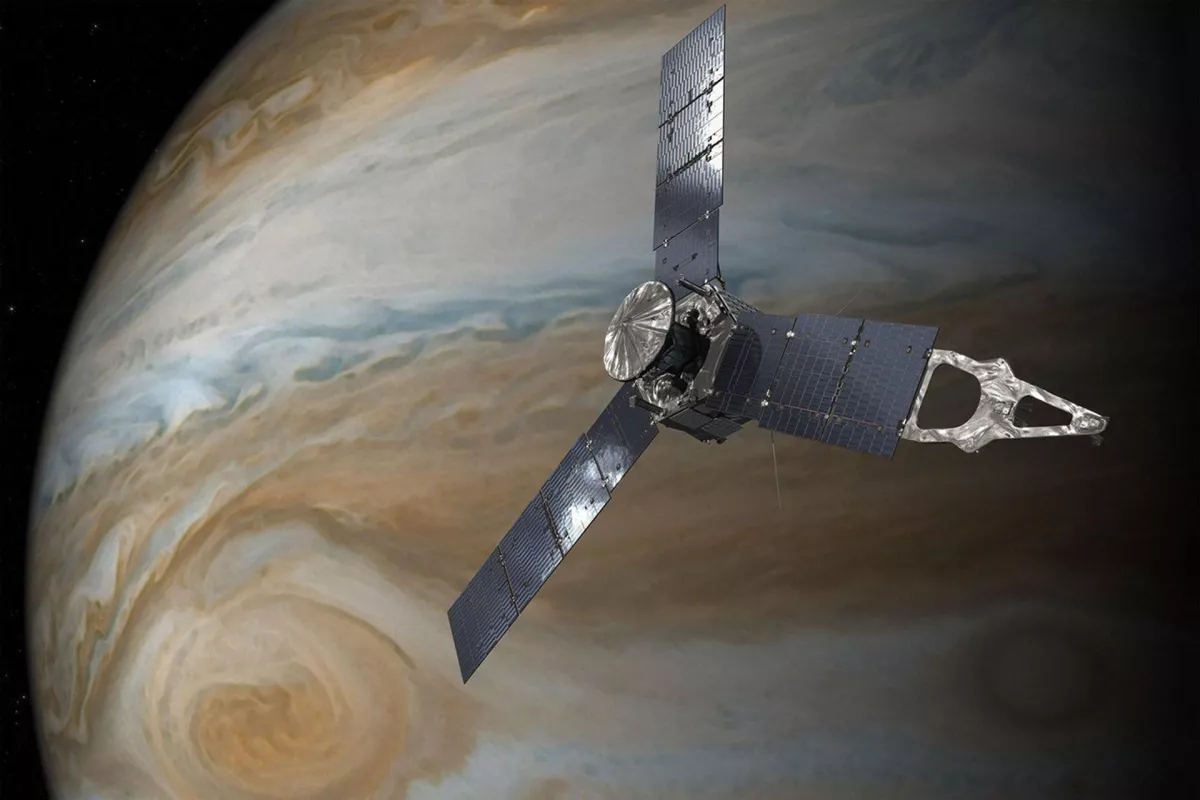

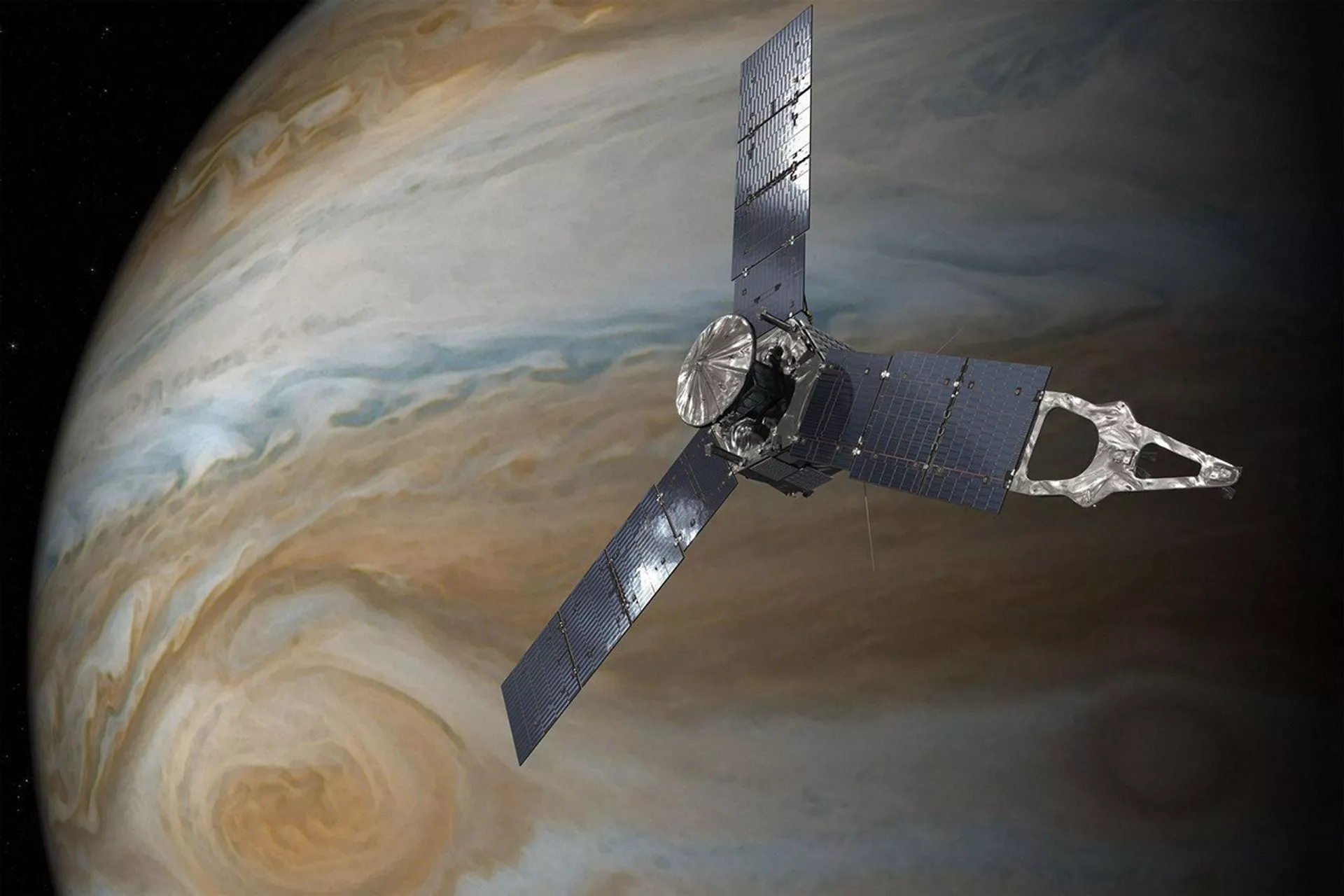

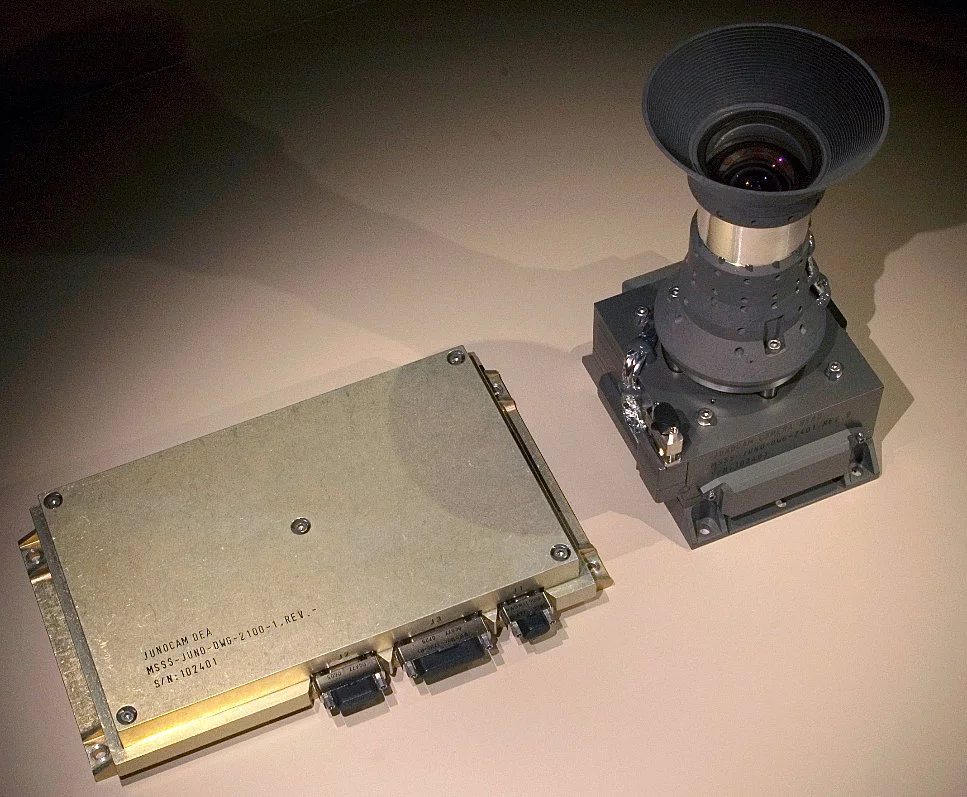

One of the key instruments aboard the robotic Juno probe currently exploring the Jovian system is its Junocam. Built by Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS), it's a visible light camera/telescope used by the spacecraft to take pictures of the cloudtops of Jupiter, as well as any moons that the probe might be flying by.

It's not a bad little Box Brownie. It has infrared filters to bring out cloud details and a neat little feature that allows it to take crisp images by compensating for spacecraft movement and low light conditions. It even helps a bit with NASA public relations by allowing internet visitors to help select targets for imaging.

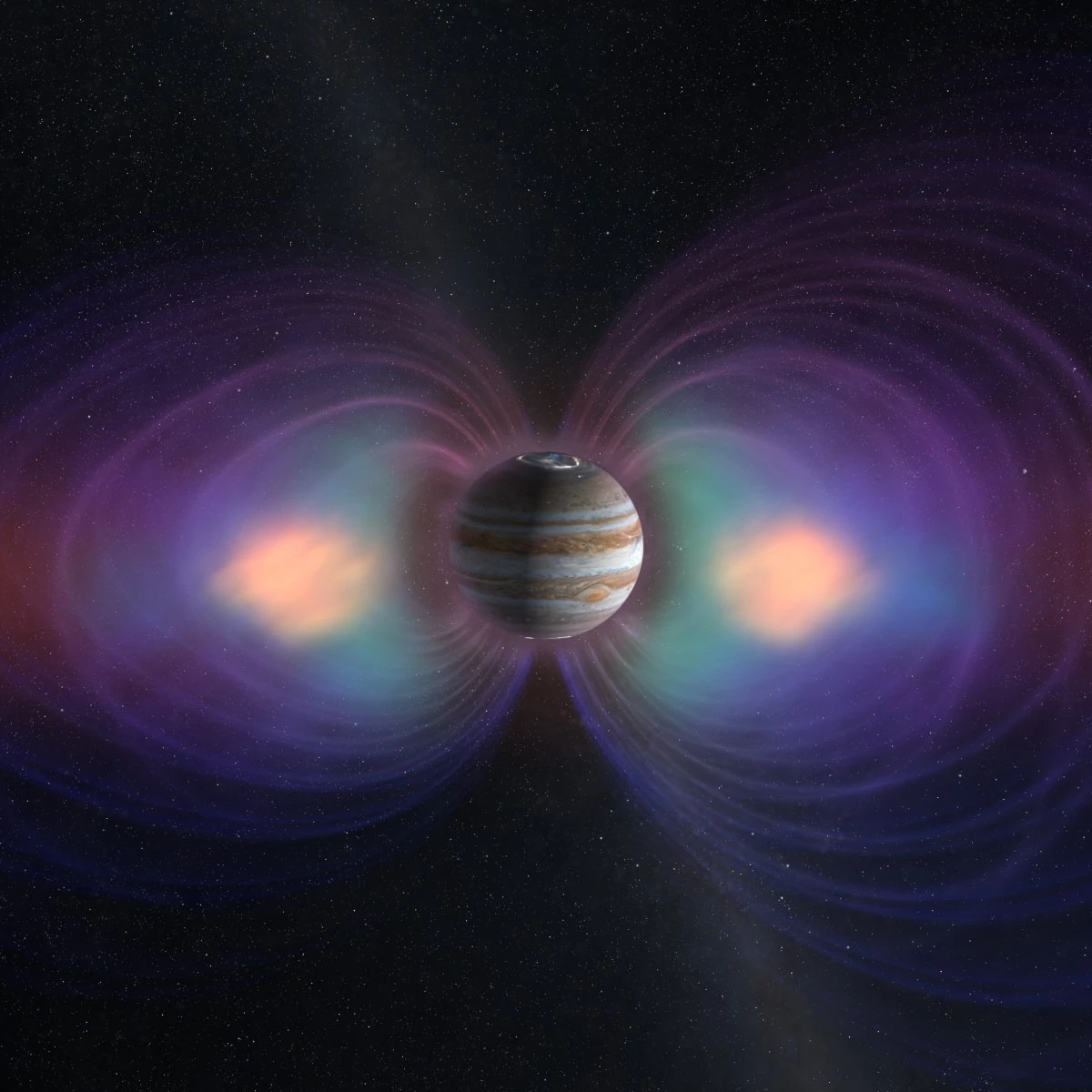

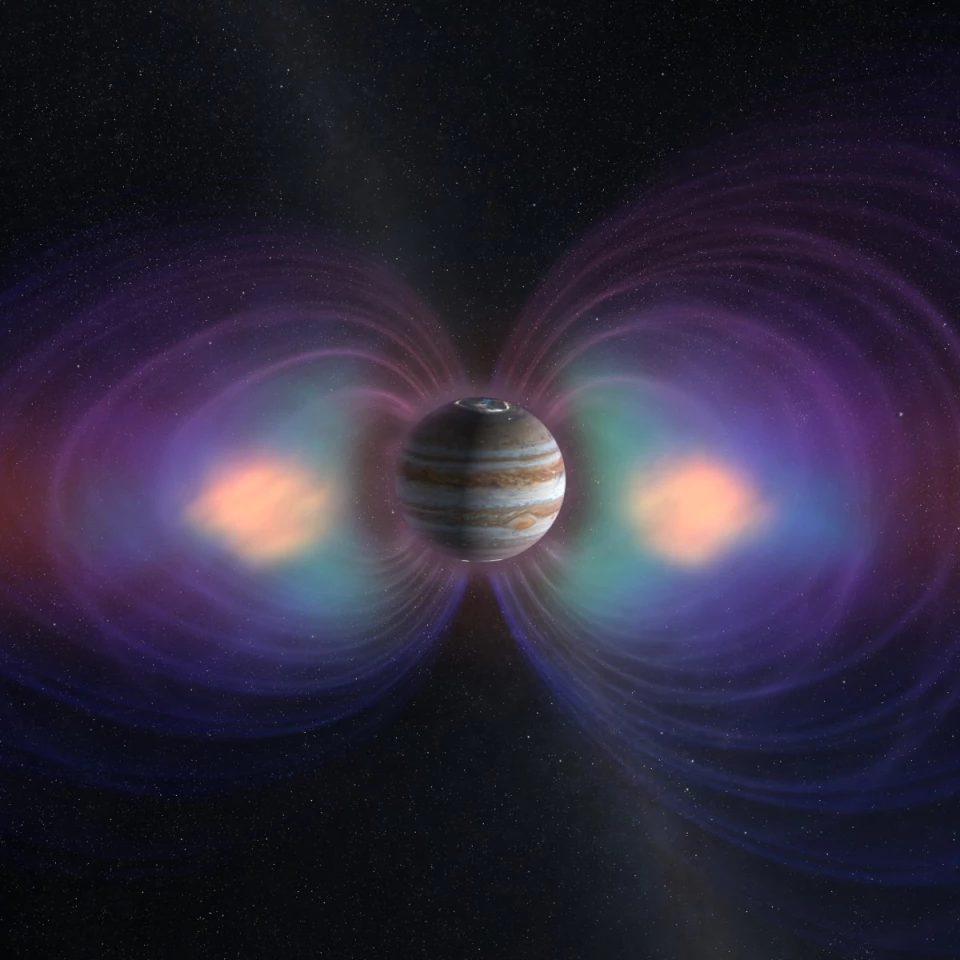

However, it's also extremely vulnerable to damage. In particular, like most solid-state electronics, it really doesn't like hard radiation. Unfortunately, that's a Jovian specialty, with exposure levels strong enough to give a human a lethal dose within as little as two and a half hours. For microchips, it's not much better.

Unfortunately, Juno is traveling in a 53.5-day orbit that is highly elliptical and regularly sends it plunging deep into the radiation belts close to Jupiter as part of its exploration mission. Normally, this would have quickly blasted JunoCam's chips, but the entire camera was encased in an armored assembly to ward off the worst of the deadly rays.

According to NASA, this worked fine during the first 34 orbits that made up Juno's primary mission, but by the time it completed 47 orbits things started to go wonky, to use a technical term. The radiation was beginning to take its toll on the electronics. Images returned to Earth were of increasingly poor quality until by orbit 56 all the images coming back were corrupted.

Some detective work traced the problem to a voltage regulator in the JunoCam's power supply. The question was, what to do about it? Since tools, disassembly, and spare parts weren't an option, the next best thing was the high-tech equivalent of giving the camera a swift kick.

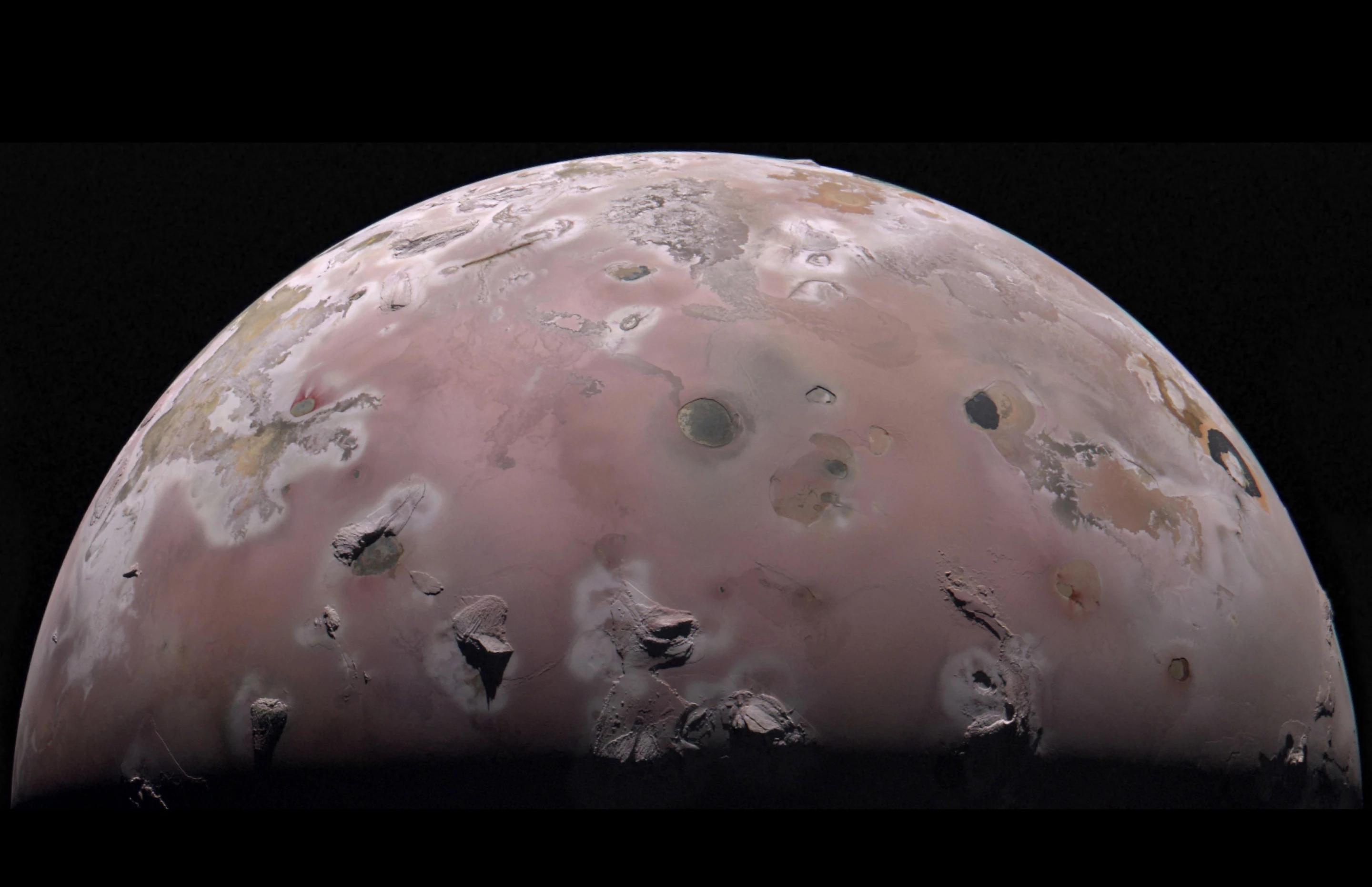

The space engineers turned to annealing. That is, using heat to change the microstructure of a substance, such as when one reverses the brittleness of overworked metal by heating and cooling. In the case of JunoCam, NASA sent orders to the probe to switch on its heaters to raise the internal temperature to 77 °F (35 °C) – which is pretty warm for Juno's neighborhood. This seemed to have some effect, but the damage also seemed to be increasing, with more streaks and noise visible in images, so they turned the thermostat as high as it would go and waited as Juno closed in on the moon Io.

As the craft passed within 930 miles (1,500 km) of Io's north polar regions on December 30, 2023, the images coming back were as good as factory new as JunoCam captured sharp images of mountain blocks covered in sulfur dioxide frosts.

While good news, Juno is still being hit with more radiation and suffering more damage, with images beginning to deteriorate by the latest 74th orbit. However, NASA now has a new widget in its toolbox and is trying out the technique on other systems aboard Juno.

"Juno is teaching us how to create and maintain spacecraft tolerant to radiation, providing insights that will benefit satellites in orbit around Earth," said Scott Bolton, Juno’s principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. "I expect the lessons learned from Juno will be applicable to both defense and commercial satellites as well as other NASA missions."

The saga of the JunoCam repair was disclosed at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Nuclear & Space Radiation Effects Conference in Nashville on July 16, 2025.

Source: NASA