A pair of extraordinary space missions that have been headed out of the solar system for almost half a century are getting a new lease on life as NASA engineers order the Voyager 1 and 2 deep-space probes to shut down two instruments to save power.

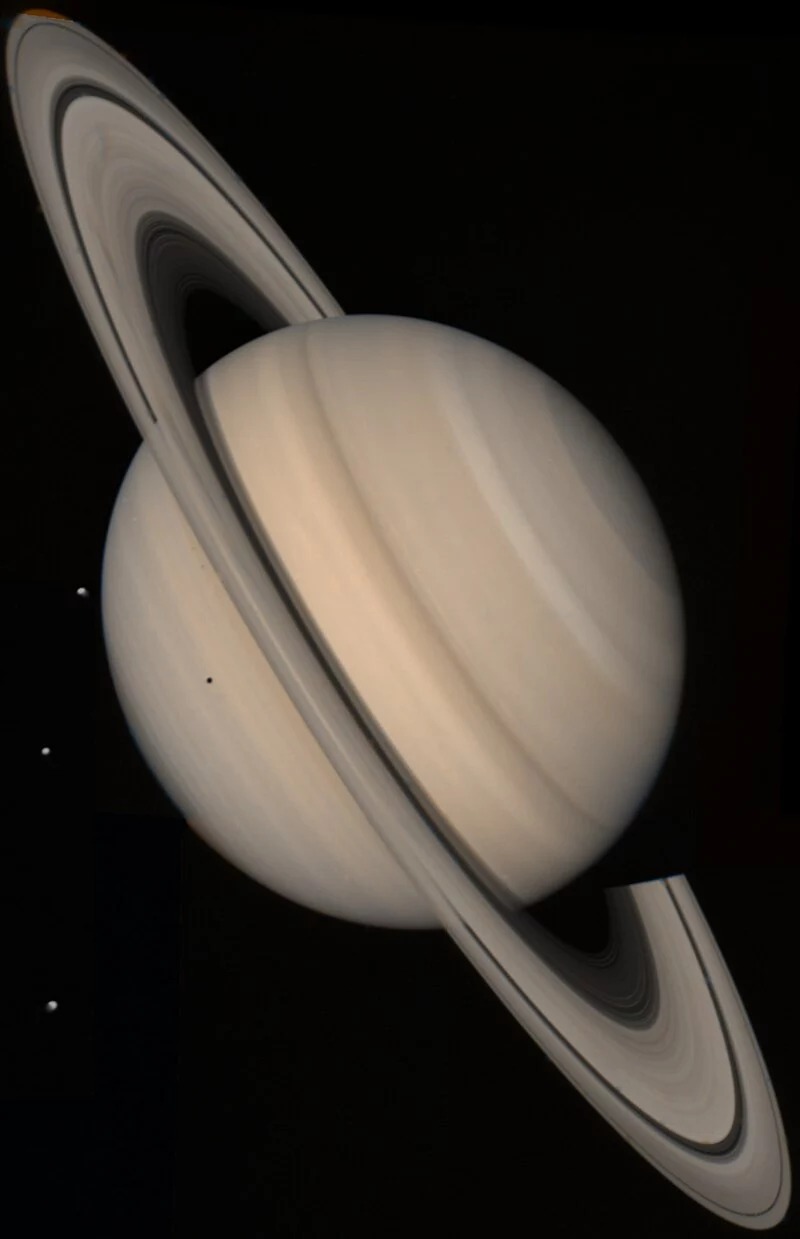

When Voyager 1 and 2 lifted off from what was then Cape Canaveral Air Force Base in 1977, they were only meant to last for about five years – giving them a comfortable time frame to visit Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. However, the two nuclear-powered robotic spacecraft were so well-built that they kept getting one mission extension after another until they are still on the job 47 years later and, barring incidents, are expected to last until their nuclear generators finally give up the atomic ghost.

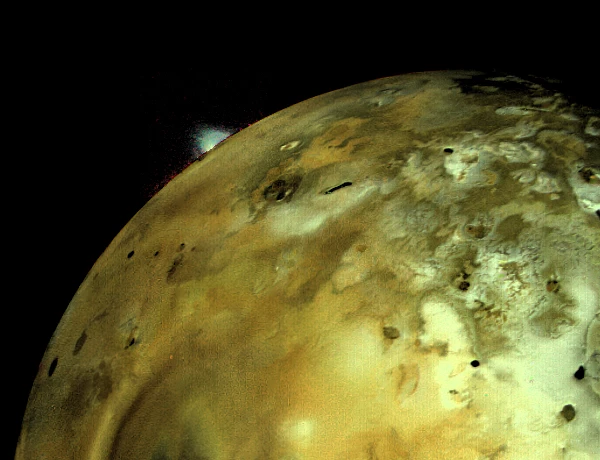

When you think about it, they are an extraordinary achievement for a whole host of reasons. They were the third and fourth spacecraft to visit Jupiter and Saturn, and Voyager 2 was the first to visit Uranus and Neptune – providing a treasure trove of information that exceeded anything from the earlier Pioneer 10 and 11 missions. They were also the first two probes to leave our solar system and the first to explore interstellar space.

Not to mention that they are the oldest active spacecraft (not counting passive satellites like geodesic laser reflectors) ever launched. To put this into perspective, everyone who was involved in the original project is now either dead or retired. The pages of the manuals and blueprints are literally turning brown with age. Even the software is so old that some very old men and women who can still understand the code have to be brought in when something goes wrong.

In addition to all this, remember that these craft are now incredibly distant. Voyager 1 is over 15 billion miles (25 billion km) from Earth and Voyager 2 is 13 billion miles (21 billion km) away. That's so far that it can take almost two days for a radio signal to make the trip to the probes and then receive a reply. To say the least, all this makes maintaining these venerable craft as they weather the intense cold and cosmic radiation of deep space a real pain.

Over the years, the Voyagers have encountered computer problems, communication glitches, thruster issues, and other concerns, but the biggest and what will ultimately doom the probes is that the radio-thermal generators (RTG) that supply them with electricity to run their systems and keep them from freezing are running down.

As their supply of plutonium-238 dwindles, the generators lose four watts of output per year. In 1977, these generated 470 watts. In 2023, this was down to 250 watts. This makes rationing the remaining power a top priority for NASA engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

Originally, each Voyager had 10 experiments in addition to the communication and support systems. Over the decades, these have been reconfigured or switched off entirely. According to the space agency, the cosmic ray subsystem experiment aboard Voyager 1 was shut down on February 25, 2025 and the low-energy charged particle instrument on Voyager 2 will be switched off on March 24. This will leave only three experiments still running. These are the Magnetometer (MAG) and the Plasma Wave Subsystem (PWS) on both craft, with an additional Cosmic Ray Subsystem (CRS) on Voyager 2 that is scheduled to be shut down in 2026.

With new power management techniques, it's hoped to extend the life of the Voyagers until 2030 or even beyond – which would be an impressive feat because the RTGs were originally only expected to last until this year. Of course, there will still be the day when the power levels drop to the point where Mission Control will have no choice but to order the mechanical pathfinders to turn themselves off completely.

But even then, they'll still have a mission to complete. Bolted to their hulls are anodized records carrying sounds and images from the planet Earth – a cosmic greeting to whatever alien life may discover them tens of thousands of years from now.

"The Voyager spacecraft have far surpassed their original mission to study the outer planets," said Patrick Koehn, Voyager program scientist. "Every bit of additional data we have gathered since then is not only valuable bonus science for heliophysics, but also a testament to the exemplary engineering that has gone into the Voyagers – starting nearly 50 years ago and continuing to this day."

Source: NASA