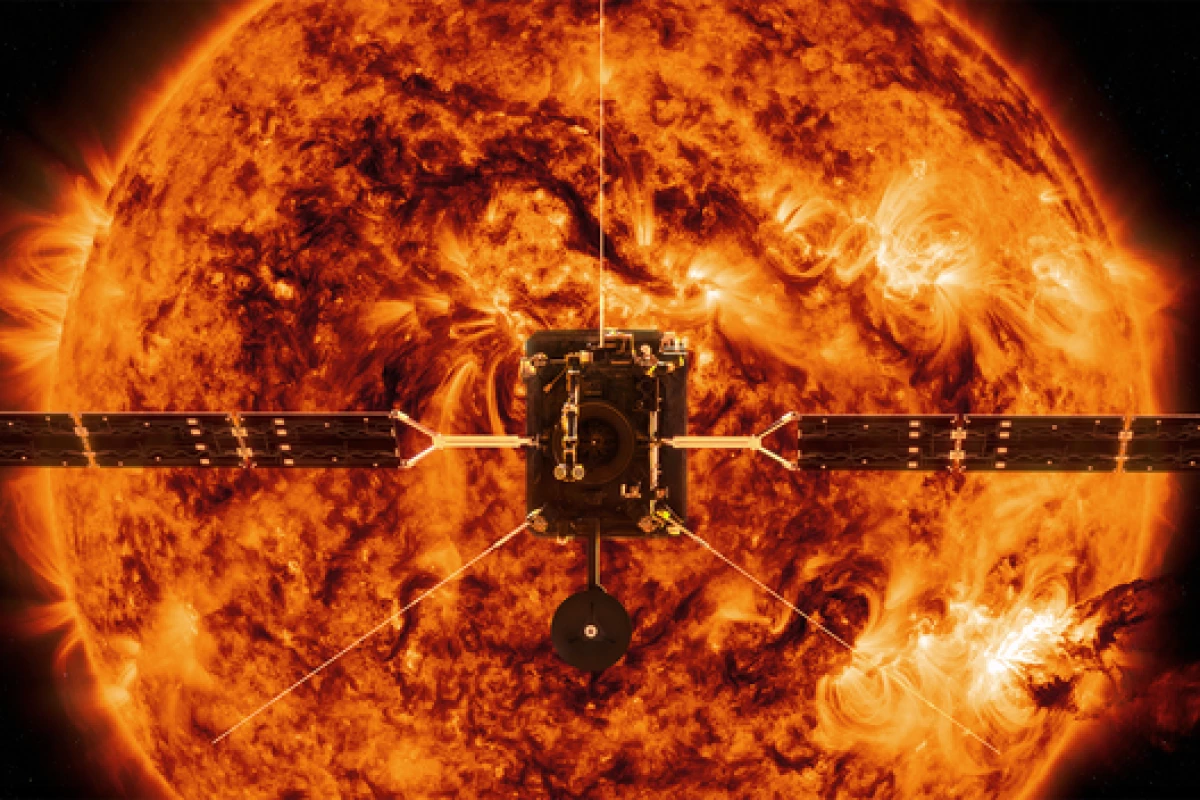

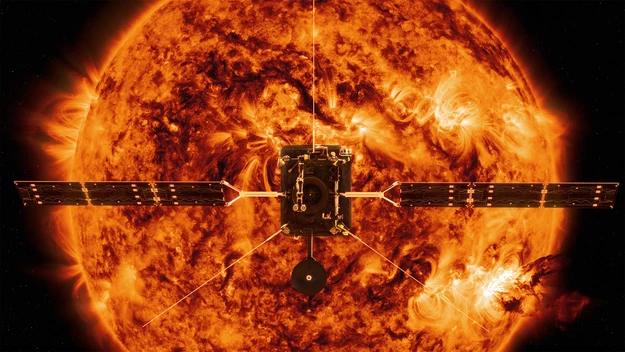

Back in February, the European Space Agency and NASA launched the Solar Orbiter, a spacecraft developed in collaboration to study the Sun in entirely new ways. Following this successful launch the probe has now made its first close approach to our star, with mission control preparing to test out the onboard instruments by gathering close-up images of the Sun and its surroundings.

NASA's Parker Solar Probe that launched in 2018 flies closer to the Sun than the Solar Orbiter, but the purpose of its mission is quite different. Whereas it will travel through the Sun's atmosphere to study the origins of high-energy solar particles and how solar winds pick up speed, the Solar Orbiter will probe our star's mysteries by gaining unprecedented perspectives on its polar regions.

It will do so through an unusual path whereby it uses the gravity of Venus to raise its orbit over time, viewing the Sun from higher and higher latitudes. Eventually, this will elevate it to an orbital path that enables it to study the Sun's poles, moving to latitudes as high as 34 degrees.

Such a feat isn't expected to take place until much later in the decade, but today marks the Solar Orbiter's first real milestone on this journey. Mission control confirmed that on June 15, the probe made its first close approach to the Sun, coming as close as 77 million km (48 million mi) from the surface, or around half the distance from the Earth to the Sun.

Following this first fly-by, the team is now preparing to test out the 10 instruments onboard the Solar Orbiter, which include energy particle detectors, magnetometers, a solar wind plasma analyzer, an X-ray spectrometer/telescope, a spectral imaging device, and a heliospheric imager. These tools are designed to investigate how the Sun creates its heliosphere through the generation of solar winds, and the next week will give the team a chance to put them through their paces.

“We have never taken pictures of the Sun from a closer distance than this,” says ESA Solar Orbiter Project Scientist Daniel Müller. “There have been higher resolution close-ups, e.g. taken by the four-meter Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope in Hawaii earlier this year. But from Earth, with the atmosphere between the telescope and the Sun, you can only see a small part of the solar spectrum that you can see from space.”

Similarly, the Parker Solar Probe doesn't carry telescopes capable of imaging the Sun directly, so the images collected by the Solar Orbiter team over the next week or so should offer a fascinating and unique perspective.

“For the first time, we will be able to put together the images from all our telescopes and see how they take complementary data of the various parts of the Sun including the surface, the outer atmosphere, or corona, and the wider heliosphere around it,” says Daniel.

Given the distance to the spacecraft, it is expected to take around a week for these images to be downloaded to Earth. The team will then get to work processing them in hopes of releasing them to the public in mid-July. Meanwhile, the Solar Orbiter will continue in this cruise phase of its mission until November 2021. It will then embark on its main science phase that will take it as close as 42 million km (26 million mi) from the surface.

Source: ESA