You have to wonder whether all of the tech bloggers who gush sentimental tributes to Steve Jobs would have actually liked the man. Numerous accounts paint a picture of a person who – in addition to his obvious charm, wicked intelligence, and inspired creativity – could be extremely rude, manipulative, and hot-tempered. It's easy to laugh these traits off when you're reading about them in a biography, but if these sappy fanboys had actually spent time with Jobs, would they still offer such moving words?

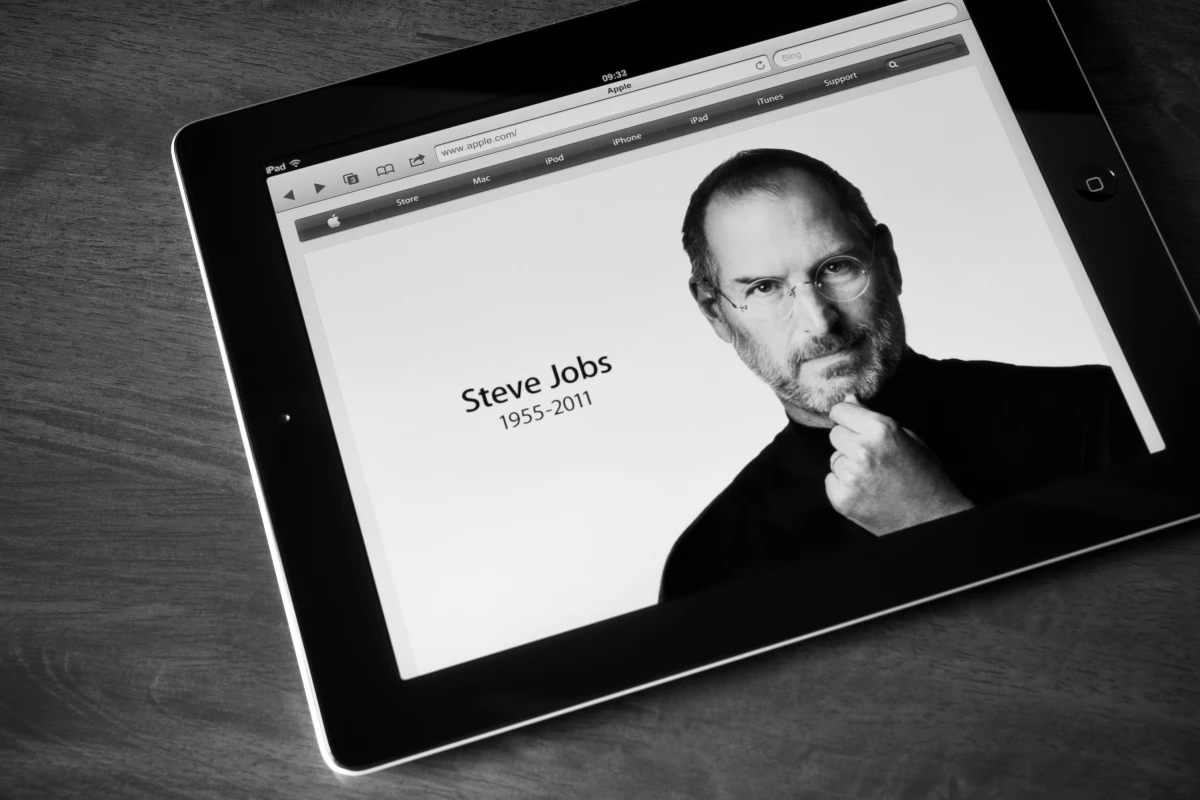

So, on this anniversary of his passing, I'm not going to pretend that I knew the man and deliver another faux heartfelt eulogy. Instead, I'm going to offer a viewpoint of Steve Jobs from the perspective of a customer.

Jobs had many unique traits that determined his success: taste in elegant design, a Jedi-like ability to see 50 steps ahead, and a charismatic "reality distortion field." You could write a book about each of these qualities. But, from my viewpoint, one attribute cemented Jobs' legacy more than any of these: his obsession with the customer's subjective experience.

Profitable subjectivity

Advertising execs have been trying to get inside customers' heads for centuries. Anyone who has watched Mad Men has seen a fascinating example of the wheels that could have been turning in a typical 1960s ad agency. What made Jobs special – perhaps more so than the fictional Don Draper – was his deep-rooted obsession with the customer's journey.

Most companies look at their products as things. They decide what this thing is going to do, what practical purpose it will solve, and how much it will cost. The product is an objective, measurable item, and their job is to figure out how to make money off of that item.

Whether it stemmed from his Buddhist views, his 1970s acid trips, or something else entirely, Jobs thought differently. He saw life – from birth to death – as an experience. Facts, figures, and objects were fine and dandy, but they were all just part of a person's subjective perspective.

Products as Events

Jobs was a dreamer – influenced heavily by 1960s cultural icons like the Beatles and Bob Dylan – and he believed that his products (much like Dylan's songwriting) took that subjective experience to a higher level. Sublime art elevated life. His goal with his products, then, was to create events.

To Jobs, a Mac wasn't just a computer that you used to get stuff done. An iPhone wasn't just an internet-connected portable media player that made phone calls. And a trip to the Genius bar wasn't just a visit to customer service. All of these things were events.

This series of events started with, well, an event: a keynote speech with Jobs on stage, laying out the framework for this next amazing experience. Soon after came the purchase of the product, which – in Jobs' later years – involved thousands of eager customers camping out overnight. Even opening the product was an event, with the package laid out so that you discovered this beautiful device in just the right sequence. Once you owned the item, every time you used it was also meant to be an event. It isn't a product, it's your life – enhanced.

Perhaps what separated Jobs from an ad exec with a marketing degree, though, was that he really believed in this perspective. To him, it wasn't just a clever tactic to sucker people into making him rich; it represented his core philosophy. The iPad wasn't just a product sold by Apple any more than Hey Jude was just a product sold by Apple Records. To Jobs, they were both art: elevating life experience from the dull and boring into something approaching nirvana.

It worked

You can argue all you want about whether this view is "true" or simply a convenient delusion. That's a discussion for another time and place. One thing you can't deny, though, is that it worked for Steve Jobs.

Jobs' genius can't be summed up in a blog post by someone who never met him. His most disruptive feature can, however, be discerned by a customer. Customers can tell when a company is only concerned with delivering X product for Y money, and when a company is devoted to something else. To millions of Apple's customers, Jobs took a sad song, and made it better.