When a baby is born preterm – between 20 and 37 weeks – it can cause significant health risks for the child as well as emotional and financial hardship for the family. Until now, doctors have mostly relied on a external device attached to the abdomen to detect premature labor, but a new internal system - developed by Johns Hopkins graduates – could detect uterine contractions very early in the pregnancy which could assist doctors to prolong the pregnancy.

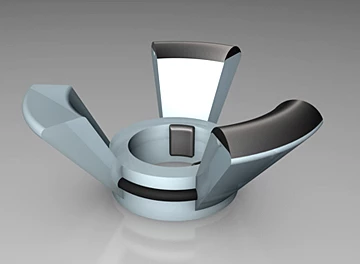

Preterm births have increased in recent years, partly because of multiple births due to the use of fertility drugs and the increase in women opting to have children later in life. Premature births are linked to neonatal deaths and serious health conditions such as breathing and digestive problems and delayed brain development. The Johns Hopkins biomedical engineering students were interested in improving the way in which doctors detect that a woman is going into preterm labor. They developed a prototype ring embedded with sensors that is designed to be inserted into the vaginal canal and can detect electrical signals associated with uterine contractions – a sign that labor has begun.

“With these sensors, we’re detecting signals directly from the places in the body where they originate, as opposed to trying to pick them up through the abdominal wall,” said Chris Courville, one of the inventors.

At this stage the prototype is being tested on animals with promising results and the students believe their system will help doctors detect early labor, resulting in the delay of preterm deliveries and allowing babies more time to develop.

“The problem is, the technology now used by most doctors usually detects preterm labor when it’s so far along that medications can only delay some of these births for a few days,” said Karin Hwang of Ontario, Calif., one of the student inventors. “But if labor can be detected earlier, medications can sometimes prolong the pregnancy by as much as six weeks.”

Hwang, along with fellow bioengineering students, Deepika Sagaram of Philadelphia; Rose Huang of Brooklyn, N.Y.; and Chris Courville of Lafayette, La worked with Abimbola Aina-Mumuney, an assistant professor of maternal fetal medicine in the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. The students have formed a limited liability corporation, CervoCheck, to help advance the project.

Initially, the students considered using a blood test to check for proteins associated with premature labor but Aina-Mumuney suggested they build something that could detect the physical signals in a pregnant woman. “I suggested that the students come up with an internal device,” she said. “I told them that if we could bypass the abdomen, that would be ideal.”

It is estimated that about 500,000 premature live births occur annually in the United States at a cost of at least US$26 billion a year. Knowing that an expectant mother is in danger of going into labor early could help to reduce the number of premature babies and reduce the cost associated with caring for them. See Johns Hopkins University for more details.