You've probably played with AI image generators by this stage. Services like DALL-E and Midjourney can create extraordinary images in response to simple text prompts. They're a ton of fun, and like many AI tools, they're improving and evolving at a freakish rate.

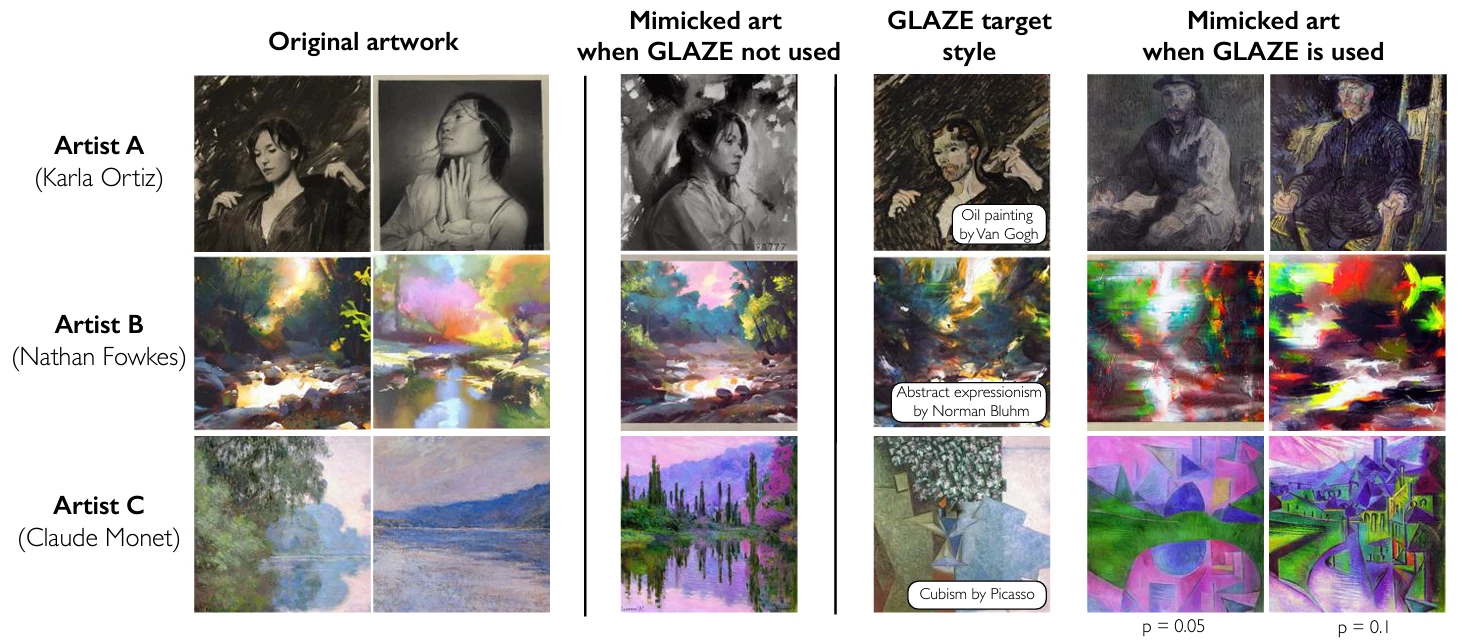

They're particularly good at imitating styles, having ingested more or less the entire history of popular art as part of their training regimes; you can freely commission your own Picassos, Van Goghs or Monets. Which to an extent is fine; these creators are long dead, having either done extremely well out of their talents while alive, like Pablo, or having died penniless like Vincent or Claude, leaving others to profit from their groundbreaking work.

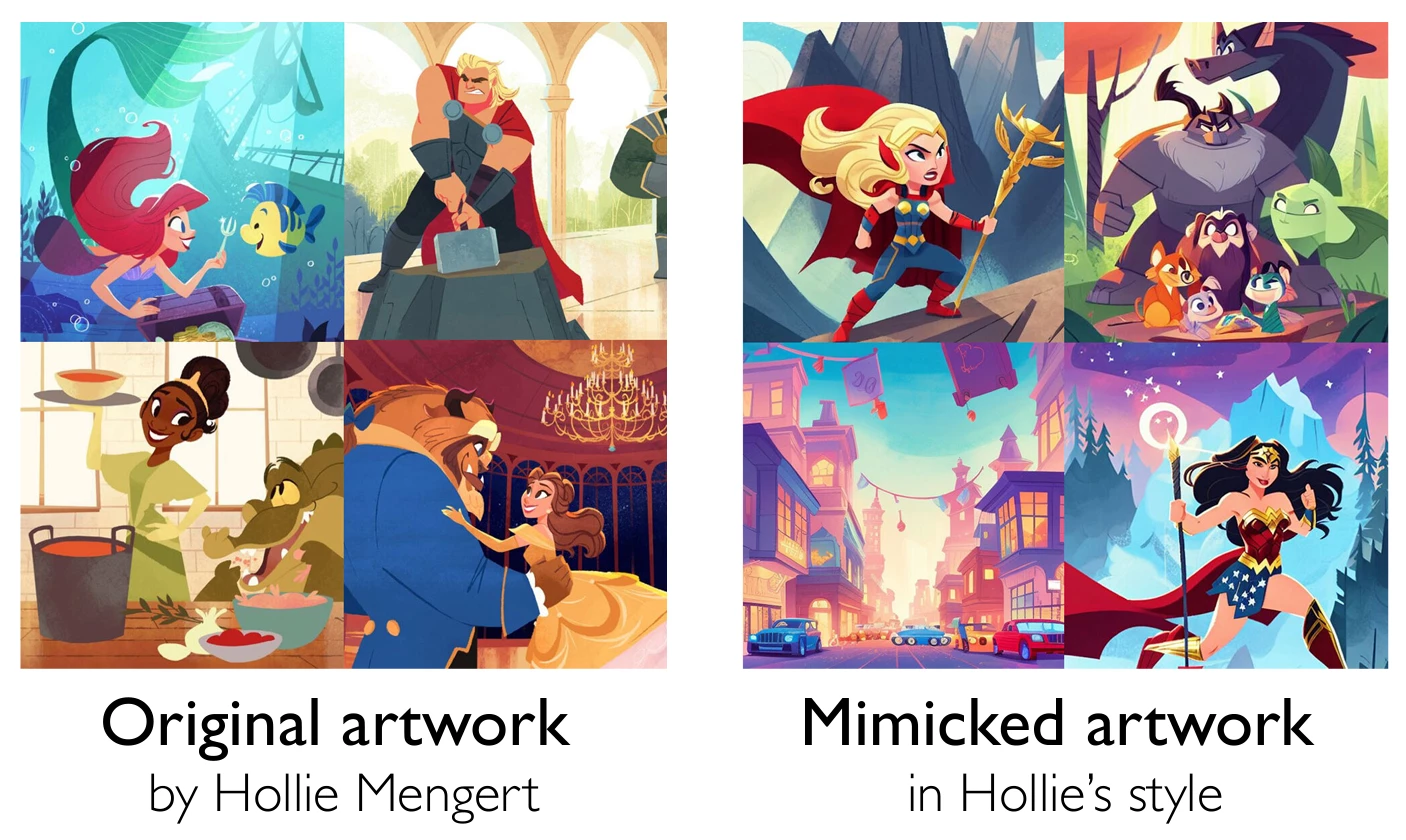

Of course, there are plenty of artists who are not dead, and who are putting their life's work into creating original works and styles. And AIs don't discriminate; they hoover up imagery wholesale, scraping it from all over the net. The more popular the work, the more likely it is to be eaten up by an AI, ready to be digested and defecated out a thousand times with zero credit or copyright for the original creator.

For sure, there's an argument that these AIs are doing nothing more than an accelerated version of what young artists have always done, working to mimic and develop on the styles and techniques of established artists as they strive to find their own voice. But when it's being done at the speed of AI, it's possible to generate derivative works at industrial scale.

The legalities are beginning to be tested; a class action complaint was filed in November against Github, Microsoft, and several OpenAI entities, alleging that many of Github's open-source AI-training libraries contain stolen images, stripped of attribution, copyright and license terms, and that these have been used to create considerable commercial value.

1/6 I created this image for everyone to use wherever they want.

— 🏮 Zakuga Mignon Art🏮 (@ZakugaMignon) December 13, 2022

Ai creates the “art” you see on the backs of artists being exploited. Ai “art” is currently scraping the web for art and uses it in datasets. No artist gave consent to have their art used. We were not compensated pic.twitter.com/eGn352MyCj

And while individual creators are up in arms, heavier hitters may soon follow lawsuit and attack on another front. Midjourney will happily create images of Darth Vader® riding a pony, or half a dozen Minions® partying in a hot tub with Buzz Lightyear®, Batman® and Bender®. In the near future, AIs will be capable of creating animated footage, overdubbed with captured voice reconstructions, making well-known characters say and do whatever a user wants in a fully custom new piece of video. You can bet the big copyright holders will move to stop that kind of thing.

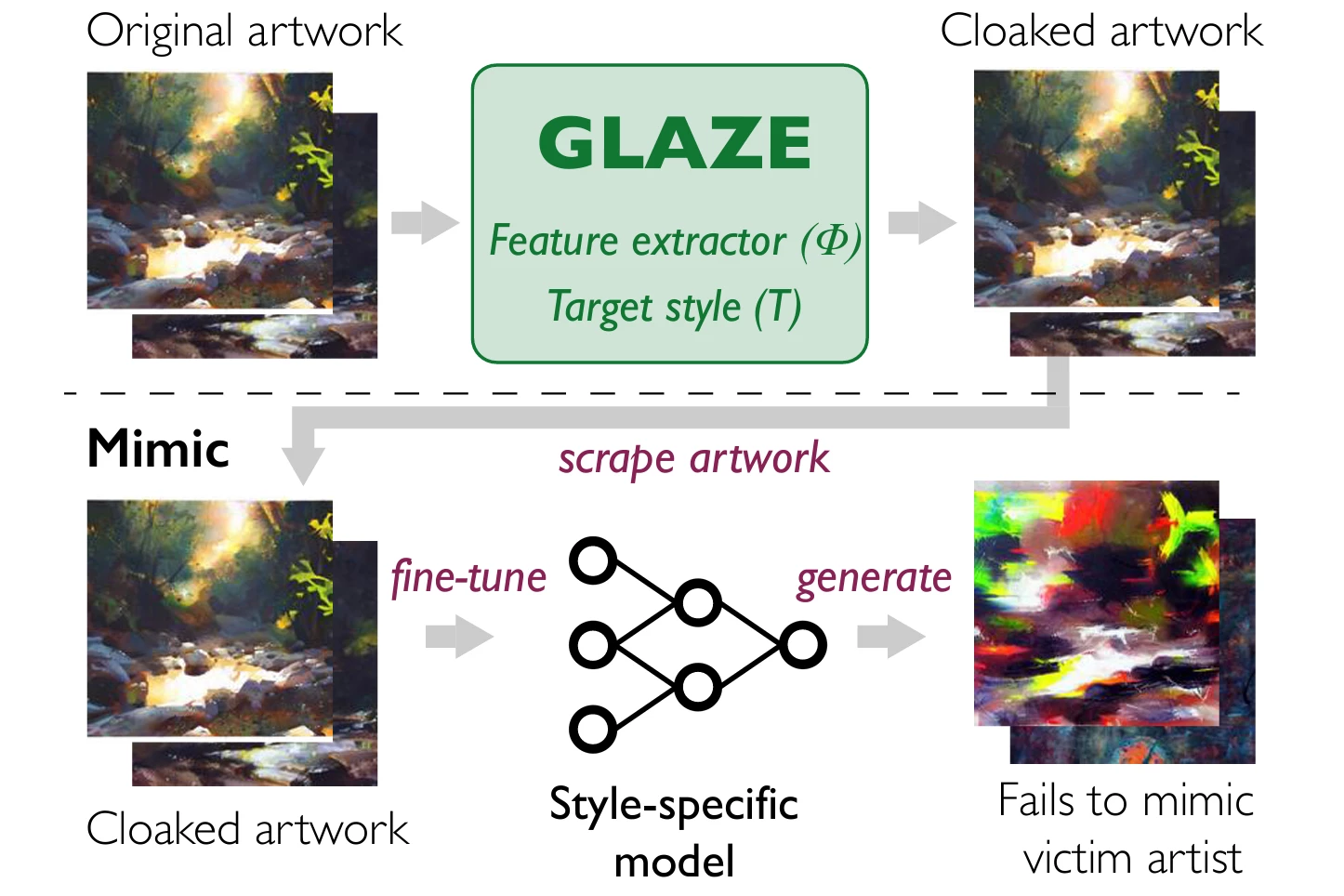

In the meantime, though, a University of Chicago team has created a kind of interim solution for digital artists. The Glaze app allows artists to make subtle modifications to their work before uploading it to be seen by the public, and potentially by thieving AI training repository collectors.

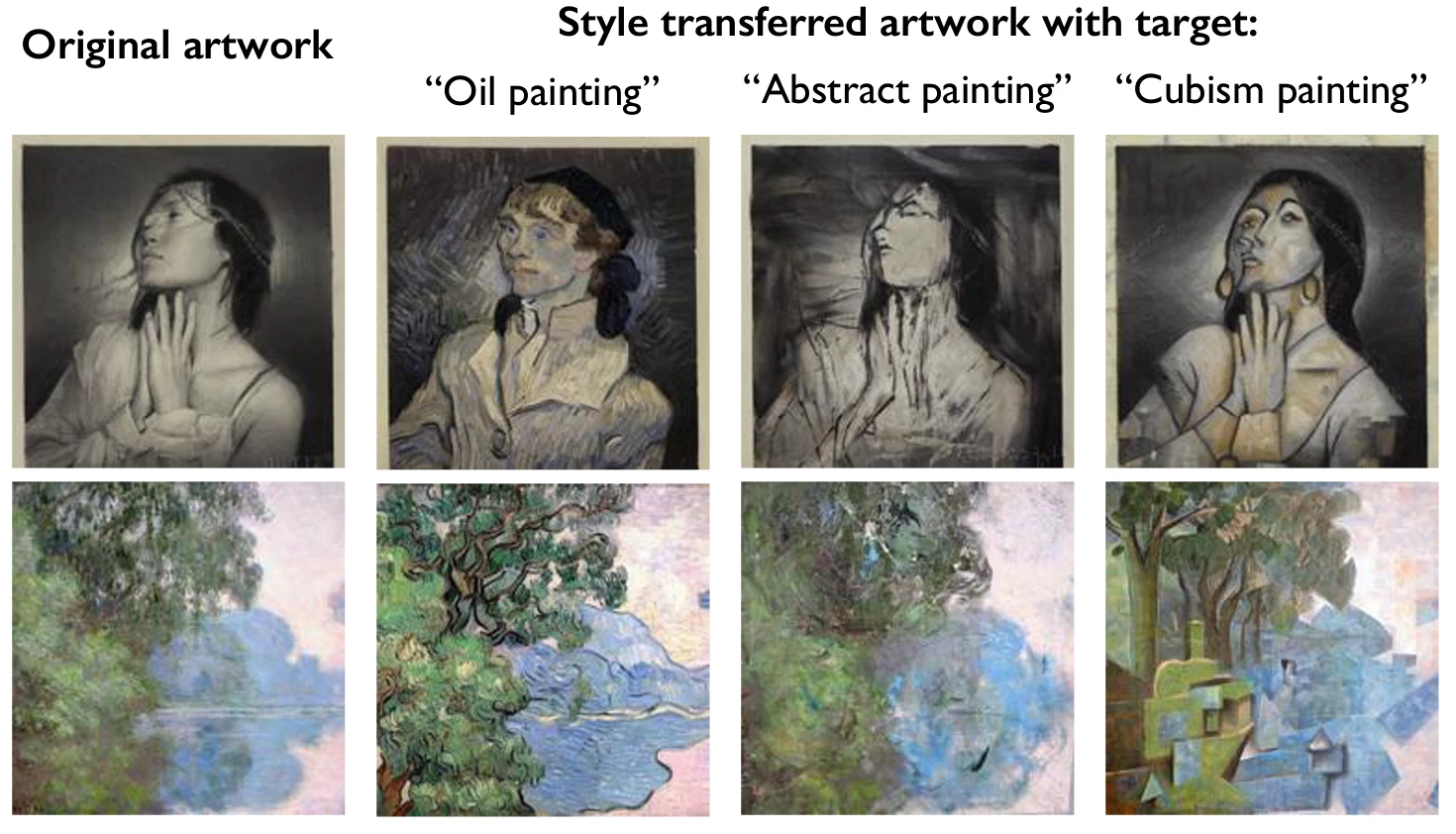

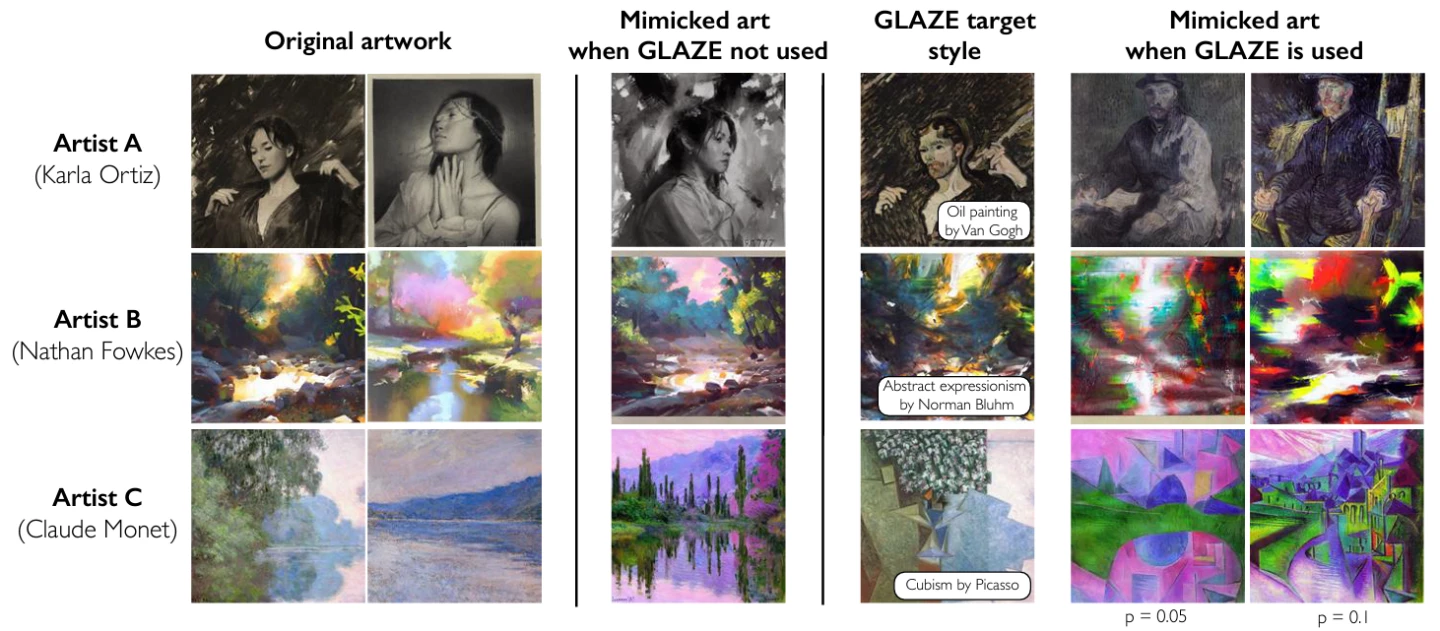

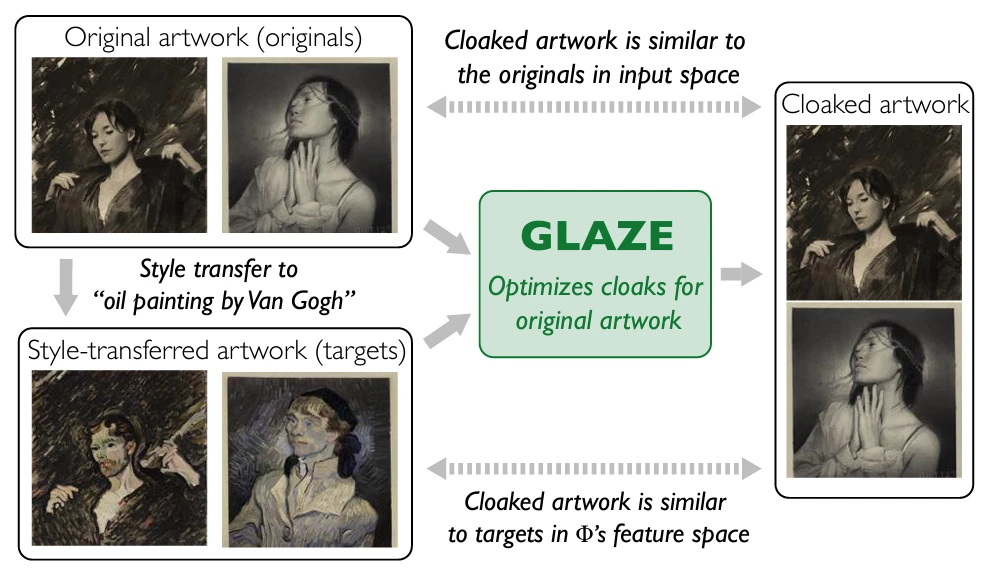

Barely visible to the human eye, these "style cloaking" modifications are designed to fool the pattern-finding capabilities of AI image tools. They make subtle changes to the pixel layouts in each image, in order to fool an AI into thinking that a new artist's style is very close to a well-established artist's style, such that if anyone asks the AI to create something in the new artist's style, it comes up with something more like a Van Gogh, for example, or at worst a hybrid of the old and new styles, ruining the results and preventing style theft.

It's quite ingeniously done. First, Glaze takes the new artist's images, and uses a style-transfer AI to recreate them in the style of famous past artists. Then, it uses that style-transferred image as part of a computation that "perturbs" the original image toward the style-transferred image in a way that maximizes phony patterns that AIs might pick up on, while minimalizing the visual impact of any changes to the human eye.

The team behind Glaze doesn't expect this technique to work for long.

"Unfortunately, Glaze is not a permanent solution against AI mimicry," reads the project website. "AI evolves quickly, and systems like Glaze face an inherent challenge of being future-proof. Techniques we use to cloak artworks today might be overcome by a future countermeasure, possibly rendering previously protected art vulnerable."

Glaze certainly has its naysayers. Some bemoan the fact that a tool like this might muddy up the algorithms and make AI image generators work worse for everybody. Others point out that Picasso himself is widely quoted as saying "good artists borrow, great artists steal," in reference to the fact that every artist is a product of their influences. In some ways, the rise of AI shines a light on just how similar humans are to these transformative algorithms in many ways, hoovering up visual, auditory and conceptual information from birth and reassembling it constantly to create "original" thoughts and outputs.

Only a few of the comments I got yesterday with the release of Glaze.

— 🏮 Zakuga Mignon Art🏮 (@ZakugaMignon) March 18, 2023

I’d like to remind you that all Glaze does is add noise so an image cannot be directly copied in Ai.

You are not entitled to our artwork. pic.twitter.com/KixBQByjd3

There's a delicious irony here, as yesterday's news about Stanford's Alpaca AI illustrates. There's another group that needs to worry about AIs stealing its work, and it's AI companies themselves. The Alpaca team used OpenAI's GPT language model to generate thousands of question-and-answer prompts, which were used to fine-tune an open-source language model, and the result was a new AI capable of performing similarly to ChatGPT on certain tasks, created for a few hundred dollars instead of several million.

Whatever the reaction from the public and the AI companies, the Glaze team believes its app is a "necessary first step ... while longer term (legal, regulatory) efforts take hold." A Beta version of Glaze can be downloaded at the project website for Windows and MacOS.

Source: Glaze