How do you create complex 3D-printed objects in seconds, instead of hours or days? A team of scientists and engineers led by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) has developed a process that uses hologram-like lasers to make complete objects in seconds inside a tank of liquid resin. Called volumetric 3D printing, the process overcomes many of the limitations of conventional additive manufacturing.

Additive manufacturing, better known as 3D-printing, promises to revolutionize prototyping and manufacturing, but it's a process that, for all its promise, has its limitations. Conventional 3D-printing works by printing an object in layers. Plastic objects can be built up by squirting molten plastic in a three dimensional pattern and metal objects by laying down layers of fine metallic dust, which is fused into a pattern using a laser or electron beam.

It's a process that allows prototypes to be produced much more quickly than machining, and it allows very complex shapes to be made in a single unit instead of being built up from several simpler units. However, such printing can still take hours or even days, and while the object is being printed it may be necessary to include ridging or temporary structures to support it until it's complete.

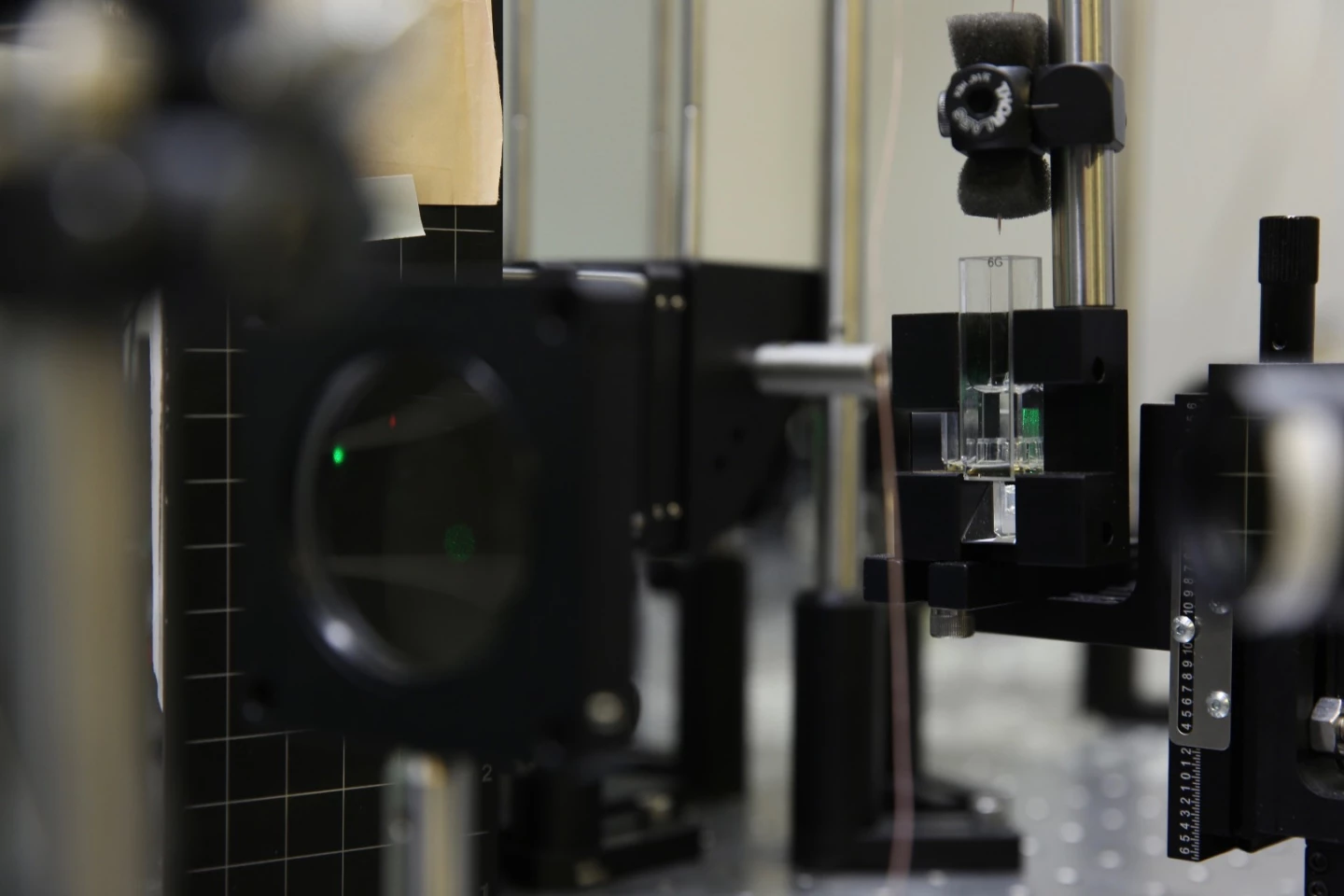

Developed by LLNL in collaboration with UC Berkeley, the University of Rochester, and MIT, volumetric printing replaces layering with a process that creates the entire object simultaneously. It does this by using three overlapping lasers beamed in a hologram-like pattern into a transparent tank filled with photosetting plastic resin. A short exposure by a single beam isn't enough to cure the resin in a short time, but combining three lasers can induce curing in about ten seconds. After the object is formed, the excess resin is then drained off to reveal the complete unit.

"The fact that you can do fully 3D parts all in one step really does overcome an important problem in additive manufacturing," says LLNL researcher Maxim Shusteff. "We're trying to print a 3D shape all at the same time. The real aim of this paper was to ask, 'Can we make arbitrary 3D shapes all at once, instead of putting the parts together gradually layer by layer?' It turns out we can."

Volumetric printing is not only faster, but eliminates the need for temporary support structures, is more flexible, and provides more geometric flexibility. So far, it's been used to create squares, beams, planes, struts at arbitrary angles, lattices, and complex, curved objects.

However, the team points out that there is a limit to how complex shapes can be and the resolution can only be increased so far because the increased exposure will cause unwanted parts of the liquid resin to cure. The hope is that the development of more responsive polymers will not only allow for larger objects with higher resolution, but also the printing of objects out of ultralightweight hydrogels. In addition, volumetric printing works in weightlessness, making it useful for manufacturing aboard spacecraft.

"It's a demonstration of what the next generation of additive manufacturing may be," says LLNL engineer Chris Spadaccini. "Most 3D printing and additive manufacturing technologies consist of either a one-dimensional or two-dimensional unit operation. This moves fabrication to a fully 3D operation, which has not been done before. The potential impact on throughput could be enormous and if you can do it well, you can still have a lot of complexity."

The research was published in Science Advances.

The video below shows the process in action.

Source: LLNL