In a groundbreaking new study, researchers have developed an electronic skin that allows humanoid robots to distinguish everyday touch from damaging force. That ability, once reserved for living nervous systems, could reshape how robots interact with the physical world and with humans in particular.

In a recent publication in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from the Technical University of Munich and collaborating institutions report the development of a new type of electronic skin designed to help robots detect harmful physical contact. The work focuses on giving robots a more reliable way to distinguish between ordinary touch and harmful physical interaction.

The work addresses a long-standing challenge in robotics: creating tactile systems that move beyond basic pressure detection and instead support safer, more adaptive behavior.

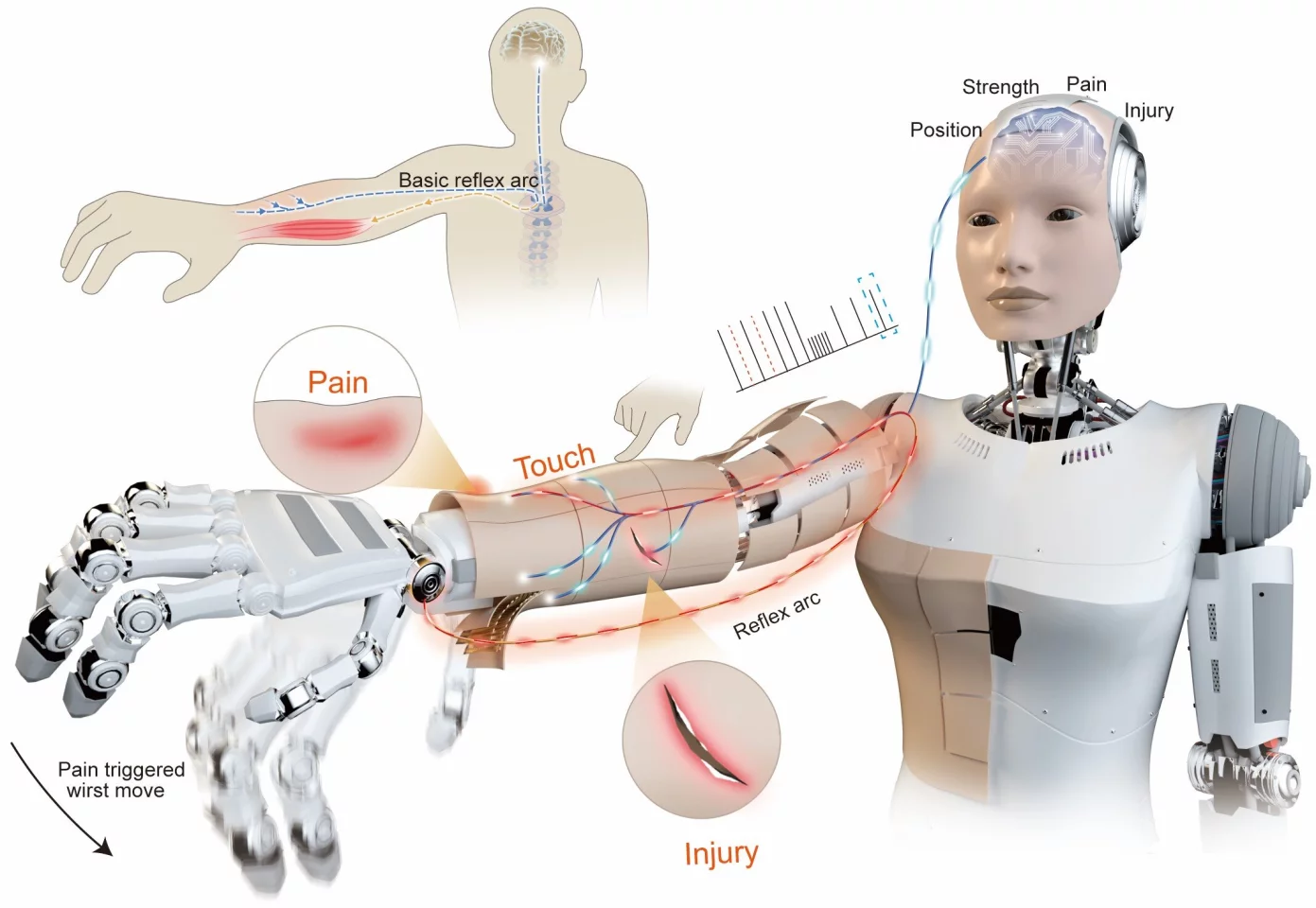

At the center of this signaling system is a network of flexible pressure sensors embedded within the electronic skin. When the surface of the skin is touched, compressed, or struck, these sensors convert mechanical force into electrical signals. Under normal conditions, these signals go straight to the robot’s central processing unit. But in the new system if a sensation crosses a set threshold, the skin reacts by instead sending a signal directly to the motors.

What makes this approach different is how those signals are processed. Instead of treating touch as a simple raw pressure input, the system uses neuromorphic encoding (modeled from biological nerves) to translate force into rapid electrical spikes. The frequency and pattern of these spikes change based on both contact intensity and location.

When forces remain within safe ranges, the signals reflect ordinary interaction. But once pressure crosses a predefined threshold, the signal pattern shifts sharply, triggering protective responses.

The researchers emphasize that the system is designed to detect mechanical stress only. It does not represent emotional pain or higher-level sensory experience, but simply provides a functional signal that allows robots to recognize harmful force and react.

“Our neuromorphic robotic e-skin features hierarchical, neural-inspired architecture enabling high-resolution touch sensing, active pain and injury detection with local reflexes, and modular quick-release repair,” the researchers write, “This design significantly improves robotic touch, safety, and intuitive human-robot interaction for empathetic service robots.”

To evaluate the system’s performance, the researchers subjected the electronic skin to a range of physical interactions, from light touch to progressively stronger forces designed to simulate potentially damaging contact. These tests allowed the team to examine how accurately the system could detect transitions from safe to unsafe contact in real time.

Across the experiments, the sensor network was consistently effective at producing distinct signal patterns and activating protective responses depending on the force applied. The system responded within milliseconds, fast enough to support real-time reactions such as pulling away from harmful contact or reducing applied force during interaction. The system also maintained stable signal performance across repeated contact cycles, indicating durability under sustained use.

These performance gains have immediate implications for safety during human–robot interaction. As robots increasingly move beyond controlled factory environments into everyday human spaces, the ability to recognize harmful contact becomes more relevant, since close-range tasks raise the risk of accidental collisions, and excessive force.

Most existing robotic safety systems are not designed for this kind of close physical interaction. Instead, they often rely on external sensors, pre-programmed motion limits, or emergency shutdown mechanisms. While effective, these approaches can be slow or inflexible. By embedding this sensing capability directly into a robot’s skin, this new system allows machines to respond locally and instantly to physical threats.

The technology could also improve performance in collaborative tasks that require physical contact, such as object handling, assisted mobility devices, and service robotics, by allowing robots to continuously adjust grip and contact force during interaction. By adjusting force in real time, robots may be able to interact more naturally with fragile objects and unpredictable environments without over-gripping, slipping, or misjudging contact.

Beyond safety and performance, the technology also reshapes how people may perceive and interact with machines. Robots that visibly react to physical stress or impact can appear more responsive and lifelike, even when no emotional experience is involved.

This kind of feedback may make human–robot interaction feel more intuitive. Just as people instinctively adjust their touch when another person pulls away, visible feedback from machines could help guide behavior and reduce unintentional damage.

Despite these potential benefits, the technology raises broader questions about how far robotic realism should go. While these sensing capabilities improve safety and performance, borrowing sensory strategies from biology, they also introduce ethical and design challenges about whether machines should mimic living responses at all.

Some researchers argue that robots do not need pain-like signaling at all. Others suggest that borrowing strategies from biology may offer the most efficient path toward adaptable, resilient machines. The challenge lies in balancing functional benefit with the risk of encouraging unnecessary anthropomorphism and its broader social consequences. What happens, for example, if this kind of sensory system in a humanoid robot is connected to an AI-managed emotional response program?

While the technology raises broader philosophical questions about robotic realism, those implications are still unfolding. For now, the system remains at an early stage of research rather than a finished commercial technology. Currently, the electronic skin only covers limited surface areas. Extending that coverage to full humanoid bodies would require not only significant advances in manufacturing, but improvements in power efficiency and data processing, as well.

Going forward, future work will focus on expanding sensor coverage and improving durability, both of which are necessary for moving the technology beyond laboratory prototypes. Each of these steps could help determine whether this new robotic skin can move from controlled laboratory demonstrations into real-world deployment.

This study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Source: TechXplore