Horizon Aeronautics is prototyping an eVTOL hovercycle concept that uses a complex and interesting split-swashplate "Blainjett" variable pitch rotor system that only exposes half of each fan. Very odd, but Horizon says it's highly efficient.

To understand how this Blainjett propulsion system works – and before anyone asks, no, these guys are no relation to me – you first need to understand how the swashplate and cyclic controls work to distribute thrust as a helicopter's top rotor spins. Each blade can vary its pitch independently, with the height of the swashplate determining the pitch. With the swashplate sitting flat, pushing the whole thing up and down will change the pitch of all the blades at once.

But with the cyclic control, helicopter pilots are able to tilt the swashplate. Pushing the stick forward, for example, tilts it such that the blades gradually tilt as they spin around, getting flatter as they pass the front of the aircraft, then pitching up to develop more lift as they go around the back. The result is an asymmetry in lift, with more at the back of the disc, and the aircraft pitches forward and accelerates in that direction. The cyclic control can do this in any direction; it's part of what makes helicopters such dynamic aircraft.

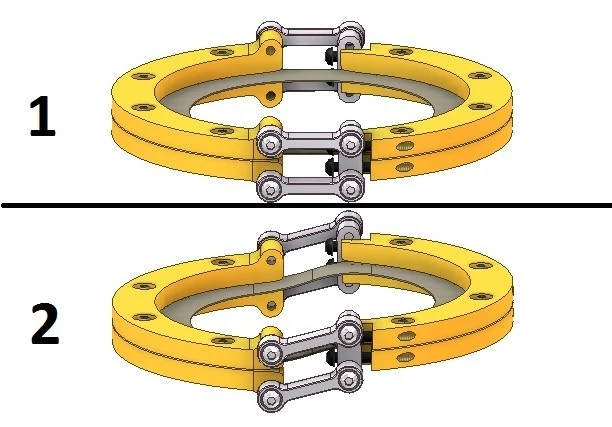

Blainjett calls its innovation "dynamic variable pitch," and what it effectively does is split the swashplate so that it operates in two halves. The swashplate still tilts as per normal in response to cyclic inputs, but this system lets you additionally push half of the swashplate higher or lower than the other half. A flexible cam made out of flex-steel and two linkages let the pitch controls move smoothly between the two levels as they rotate.

Why? Well, originally the Blainjett system was designed to counter retreating blade stall. As a helicopter accelerates forward, an asymmetry of lift develops. As the top rotor blades spin around, they go toward the front of the aircraft on one side, and backwards on the other. At high speeds, this means the blades develop extra lift as they're going forward into the fast-moving airstream, and less lift as they're retreating backward with the airstream, and the final result is asymmetry of lift, leading to a speed limit beyond which the aircraft will tip over and plummet.

Pilots can and do balance against this effect using the cyclic control, but Blainjett says that its split system makes for a quicker transition between the halves, increasing the average pitch angle on the retreating side and decreasing it on the advancing side. Thus, helicopters could theoretically balance out lift asymmetry more effectively and raise their maximum speed.

Blainjett says, "Data from our proof of concept prototype showed a significant improvement of 75 percent, with a 125 percent improvement projected in future testing," although it's unclear exactly what was improved by 75 percent.

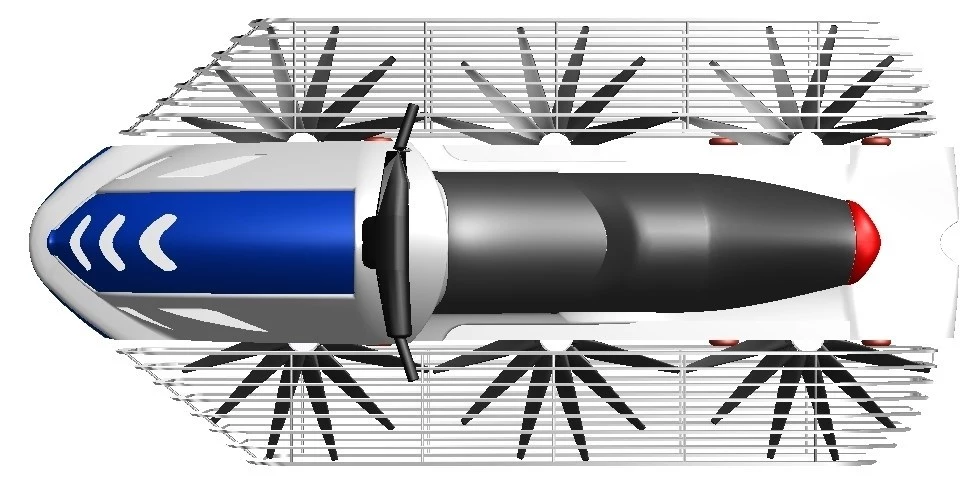

No matter; on to the Horizon hoverbike. Horizon wants to build an eVTOL aircraft about the size of a jet ski. It would weigh about 380 kg (838 lb), or a little less than two sports motorcycles, it'd have a roughly 9 x 4-ft (3.58 x 1.270m) footprint, and it would be capable of seating between one and three very brave humans on board.

Horizon's problem, as Blainjett tells it, was efficiency. Airflow through the hoverbike's side skirts would only allow the use of small-diameter ducted fans. Small fans use more power in a hover, and since this bike would be hovering constantly, Horizon was struggling to carry enough battery to feed them for a useful length of time.

Enter Blainjett's dynamic variable pitch system. The hoverbike is now configured using three large rotors in line down each side of the bike – much bigger than the bike's footprint allows space for. So they're designed such that only half of each blade is exposed, with the other half disappearing under the bodywork. The Blainjett system splits the rotors so that they're totally flat for neutral lift as they go through the bodywork, then pitched up as they exit.

"Horizon Aeronautics has real space and power constraints," explains Blainjett president Cary Zachary. "When we realized that we could nest the lift rotors in a certain way that maximizes space available and combine their placement with our vectored thrust concept, we knew we had something unique."

The system allows for variable lift, as well as a certain degree of vectored thrust. But most importantly, it gives Horizon a vastly more efficient large-diameter rotor system that's much more efficient than using smaller fans. "It turned out when we compared our thrust output and efficiency to ducted fans and smaller rotors we were two to three times more efficient with two to three times more power density while fitting in the same available space," says Zachary. "There's also a reduction in aerodynamic drag in forward flight."

It's a very specific solution for a very specific problem, on a very specific type of vehicle that we're frankly a little unsure about. The hoverbike doesn't appear to be intended for high-altitude use – indeed, the idea could well be to stay low enough to take advantage of ground effect. So in one sense you've got a shorter distance to fall if things go pear-shaped, but in another sense there's a whole lot more stuff to crash into if you stay close to the ground.

Horizon's own website is pretty barren, saying little beyond, "We make flying hover vehicles revolutionizing short distance travel for the urban commuter." But Blainjett says the company is working on a fully functional prototype that should be ready for testing later this year. We won't be holding our breath, but we thought this was an idea that our wonderfully technically minded readership might find as curious and interesting as we did – or at the very least rip the concept to shreds in what's bound to be an entertaining comments section. Fire when ready!

Sources: Blainjett via PRNewswire, Horizon Aeronautics