A West Texas company says it's found a remarkably simple way to slash air cargo costs as much as 65% – by having planes tow autonomous, cargo-carrying gliders behind them, big enough to double, or potentially triple their payload capacity.

The idea certainly isn't a new one – payload-carrying gliders were towed toward combat zones in World War 2, full of troops and/or equipment, then released to attempt unpowered landings in the thick of things – with widely variable results, particularly where stone-walled farms were a factor.

More recently, the US Air Mobility Command tried flying one C-17 Globemaster III some 3-6,000 ft (900-1800m) back from another, "surfing" the vortices left in the lead plane's wake – much like ducks flying in formation – and found there were double-digit fuel savings to be gained.

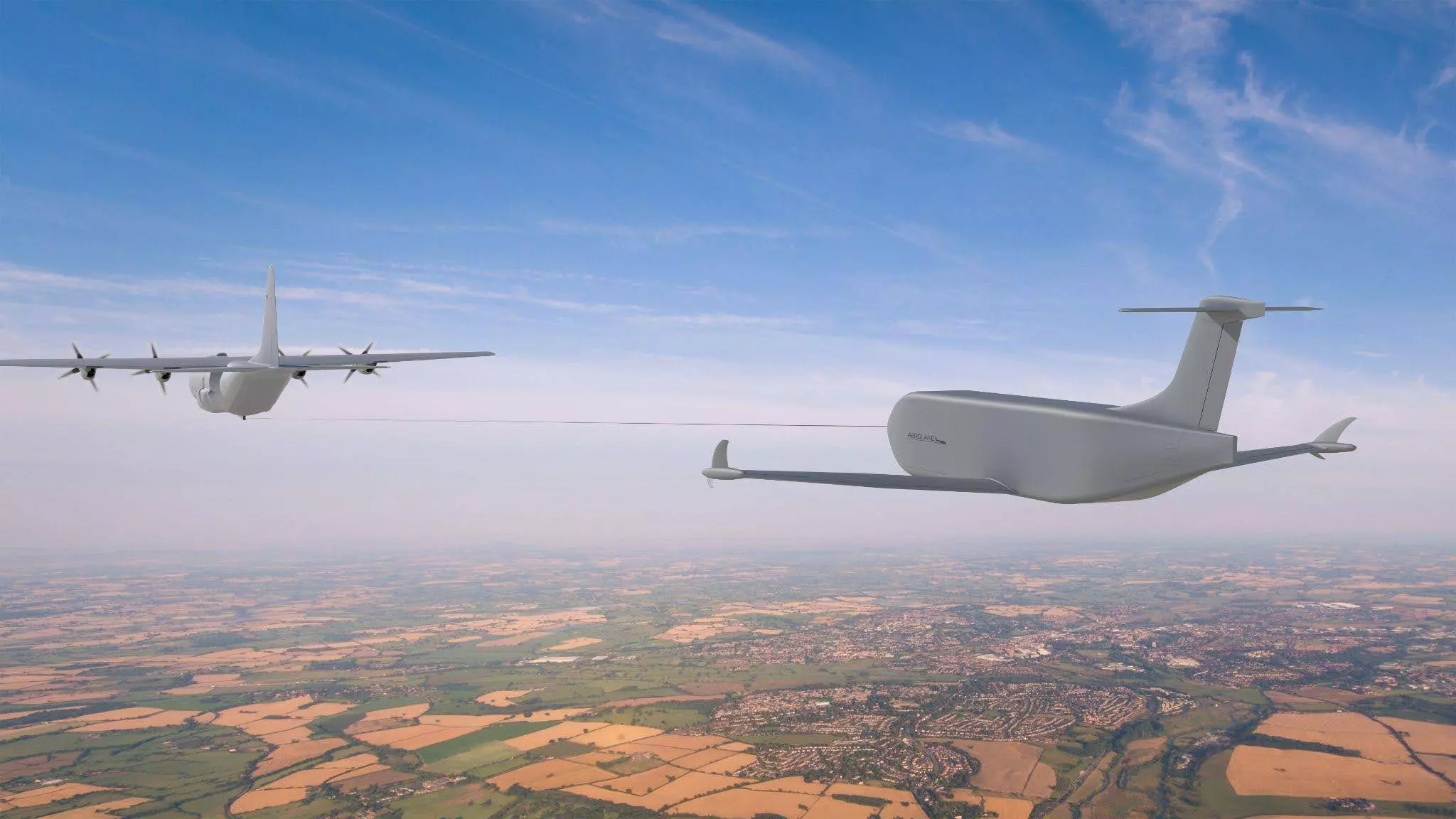

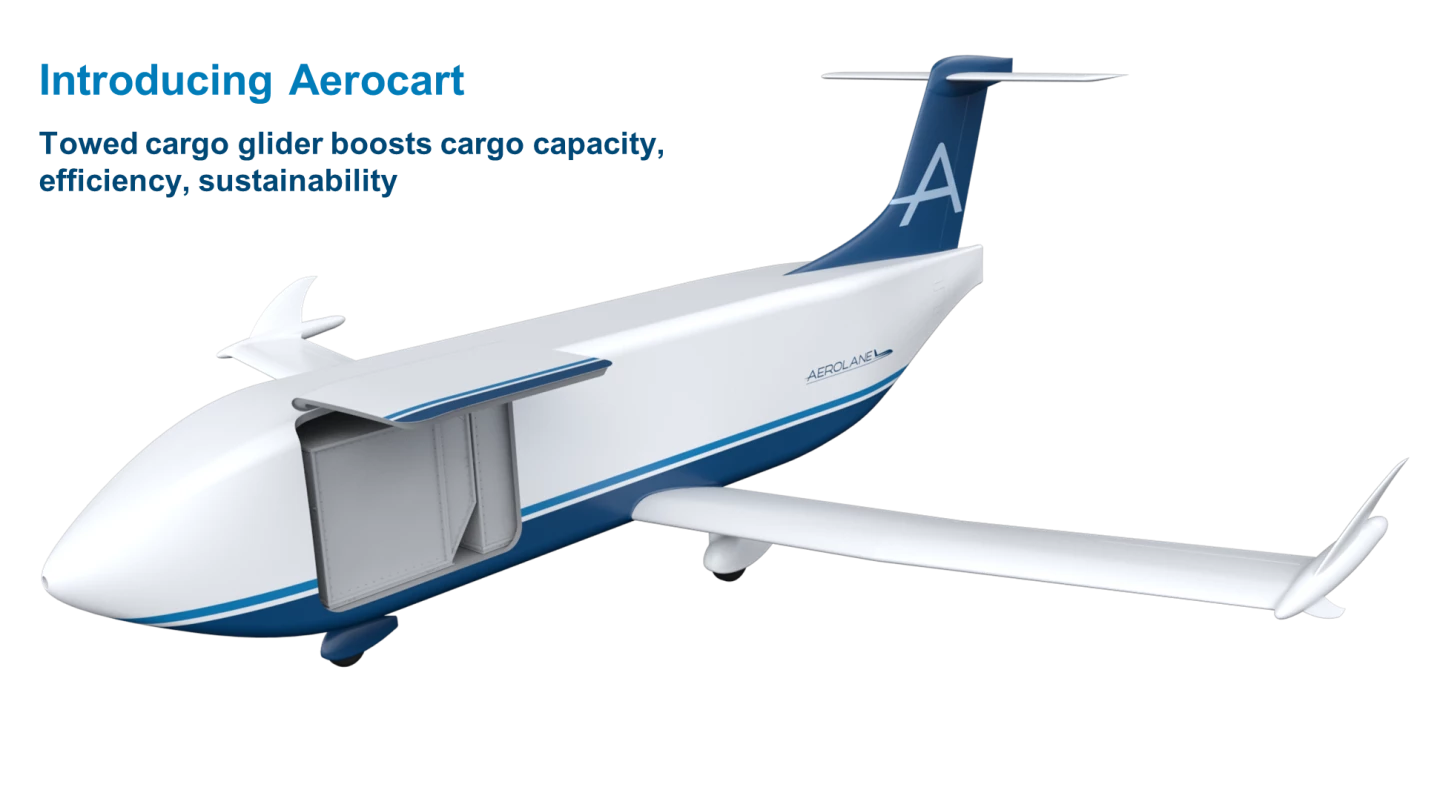

But Texas startup Aerolane says the savings will be much more substantial with purpose-built autonomous cargo gliders connected to the lead plane with a simple tow rope. With no propulsion systems, you save all the weight of engines, motors, fuel or batteries. There'll be no cabin for a pilot, just space for cargo and the autonomous flight control systems that'll run them.

These "Aerocarts" will be pulled down the runway by the lead plane just like a recreational glider. They'll lift off more or less together with the lead plane, then stay on the rope throughout the cruise phase of flight, autonomously surfing the lead plane's wake for minimal drag and optimal lift. And they'll either land right behind the lead plane, rope still attached, or eventually possibly be released at an ideal spot so they can make their own descent, potentially landing at an entirely different airstrip than the lead plane.

The latter would require some regulatory wrangling, but otherwise, according to Bloomberg, Aerolane believes it shouldn't be treated much differently by the FAA than regular ol' recreational gliders. It remains to be seen how the FAA will feel about this.

The company is, however, already flying two "automated tow cargo glider" prototypes, as shown in the video above, and has been doing so since 2022. The first is a converted 1,000 lb Pipistrel Virus, the second is a rather spunky-looking Velocity SE canard pusher, that's also been converted for the job. Both run Aerolane's own autopilot system, designed specifically for efficient vortex surfing.

Both still have engines in them, but Aerolane is working with the FAA to get authorization to start building aircraft without powertrains, using lightweight materials. At that point, it'll look to build a 3-ton cargo glider, then a 10-ton version.

The company has raised about US$11.5 million in seed funding to get things started, and has set a target date of 2025 for "initial availability." It doesn't have any early customers signed up yet, but once it gets custom prototypes benchmarked, the idea of "the speed of air at the cost of ground" could well get freight operations interested, even if these tow-gliders are sure to drop jaws everywhere one takes off or lands.

Source: Aerolane