In a feat that can only be described as legendary, and after many months and a catastrophic setback, Polaris Spaceplanes has finally accomplished something that's never been done before: lit the fuse of an aerospike rocket in flight.

On October 29, 2024, over the Baltic Sea, Polaris Spaceplanes conducted a test flight of its MIRA II aircraft. The rocket-equipped plane followed a predetermined flight path on autopilot, powered by its four kerosene jet turbines, before successfully igniting its AS-1 LOX (liquid oxygen)/kerosene linear aerospike rocket engine for three seconds in flight, marking the very first ever test of an aerospike rocket in flight.

This is the first of more test flights to come. Polaris reported an acceleration of 4 m/s² and 900 newtons of thrust from the 16.4 ft (5 m), 505 lb (229 kg) airframe.

That means the MIRA II accelerated about 9 mph (14.4 km/h) every second with enough thrust to defeat gravity and lift a 200 lb (90 kg) person straight up into the air.

Around 12PM that same day, Polaris performed a successful rolling tarmac test of the aerospike rocket engine and only hours later took flight.

The flight was conducted with a light load of fuel and took three and a half minutes to cover over 6 miles (10 km) before returning home. After aerospike ignition, there was a small leak in the LOX tank that caused an access hatch to be lost in fire, but otherwise, the MIRA II airframe is unharmed.

Earlier, in May of this year, the MIRA I was to be the first aerospike flight test, but crashed during take off. Polaris went ahead and built the larger MIRA II and III stating "At Polaris, we are advancing our project at an exceptionally rapid pace. To facilitate such swift progress, we fully accept that sometimes things can break... If you don’t break things, you are not ambitious enough."

MIRA II – and its identical twin, the MIRA III – is fitted with an AS-1 LOX kerosene linear aerospike rocket that was developed in-house by Polaris. Though the concept of aerospike rocket engines has been around for 70 years, one has never been used outside of a lab and never in flight.

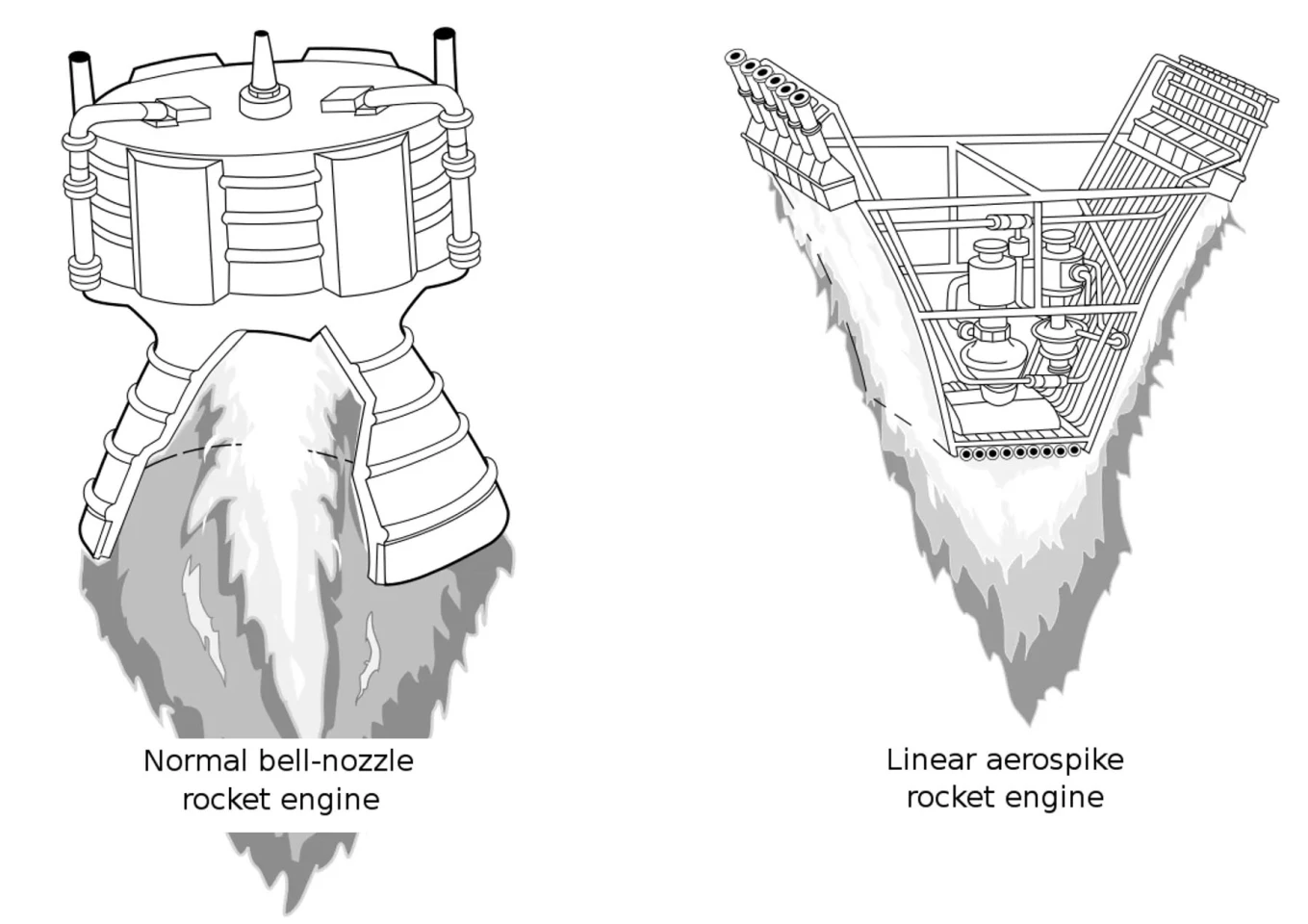

What makes an aerospike rocket unique is essentially inverting a traditional bell-shaped rocket nozzle. Instead of enclosing the exhaust, it forms an inward-facing curve, with the exterior side open to the surrounding atmosphere. The reason for this design choice addresses the limitation of traditional bell-shaped rockets, which are optimized for maximum efficiency at a single altitude. As the rocket climbs and atmospheric pressure decreases, these nozzles become less efficient, requiring separate rocket stages with different nozzles of different shapes and sizes to perform efficiently as the rocket gains altitude. With the aerospike design, atmospheric pressure acts as the external nozzle shape, providing better average efficiency at all altitudes.

Why haven't we been using aerospike rocket engines if they've been around for 70 years?

Rocketdyne invented the design in the 1950s. The designs were more complex and tended to be heavier than the traditional bell-shaped rockets. They require more cooling as the entire engine length is subjected to intense heat. Advanced materials to cope with these cooling issues weren't cheap or widely available and traditional rockets were proven to be reliable, so the aerospike design never fully took hold and remained in the lab.

In the 1990s, NASA and Lockheed Martin began the X-33/VentureStar program with the aim of making a single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) craft that would feature a linear aerospike rocket. A prototype was partially built until once again, complexity and cost led to the program's termination in 2001.

Polaris is essentially picking up where NASA left off.

The MIRA II and III are scaled-down demonstrators that will eventually lead to the Aurora, Polaris' reusable space launch and hypersonic transport system that functions like an aircraft. Next to be built is the Nova, a 23-26 ft (7-8 meter) airframe, which will be the final test aircraft before Polaris sets its sights on Aurora.

Watch the test here.