Want an induction stove that plugs into a standard 120-V power socket? After a gradual rollout this spring, the Copper Charlie is now available across the US.

If you’ve never made dinner on an induction cooktop, you’ve a treat in store the first time you try one. Mine came 15 years ago at an apartment I’d rented in Paris, and I’ve extended the experience across memorable meals at the home of a friend.

The first thing you notice is how responsive the stove is. Where a traditional electric stove heats an element under your pot, an induction stove heats just the pot. And when you turn down the setting, there’s no hot coil or lingering gas flame to resist the adjustment.

For much of my life I’ve been cooking with gas, long the benchmark for speed and precision. The induction stoves I’ve used have felt faster, gone just as hot and set more swiftly to a reliable simmer.

Spills tend not to stick hard to the cooktop’s glass surface, which is heated only by contact with your cookware. There’s no gas seeping into your household environment, and no risk that a naked flame will set fire to your kitchen.

With so much going for it, you’d think we’d all be cooking with induction by now. The technology is more than a century old, and it’s a half-century since commercial induction stoves were first shown.

But while the technology is now widespread in Europe, take up has been slower in the United States and other parts of the world. Traditional electric stoves have been cheaper, and a gas-fueled kitchen may need an additional high-voltage and/or high-current circuit to handle the power draw from a change to induction.

If you’re doing a kitchen remodel in North America, however, Berkeley, California-based startup Copper has just removed that rewiring hurdle, announcing that its Charlie stove is available for delivery in every contiguous state. It's also working on adding Alaska and Hawaii to that list to check off the full 50.

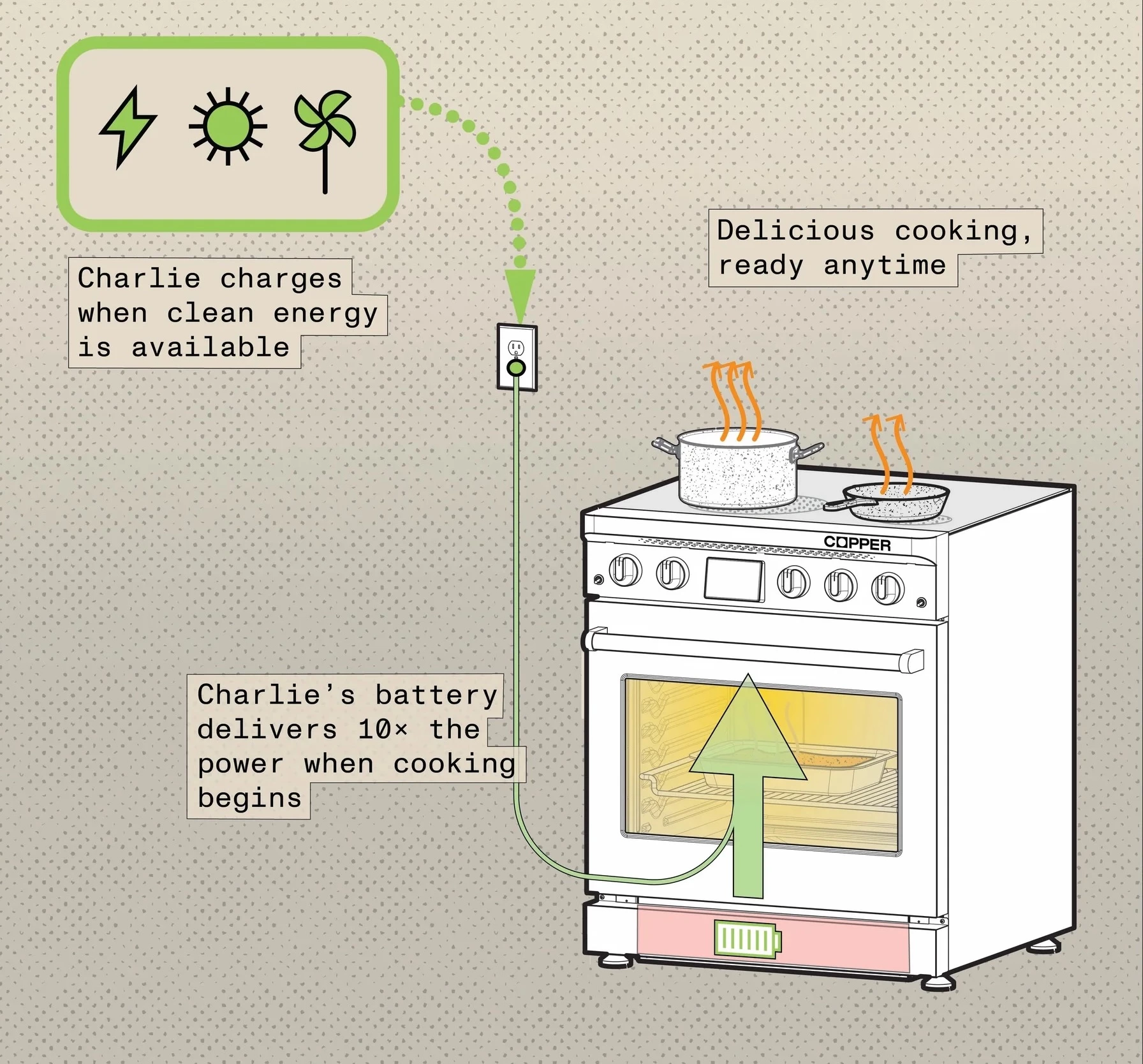

The Charlie hides a 75-lb (34-kg) lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) battery in a compartment beneath its oven, which can charge from the 120V mains socket ubiquitous in the US.

The battery supplies high current on demand to the stovetop’s four induction elements and to the conventional radiant elements inside its oven.

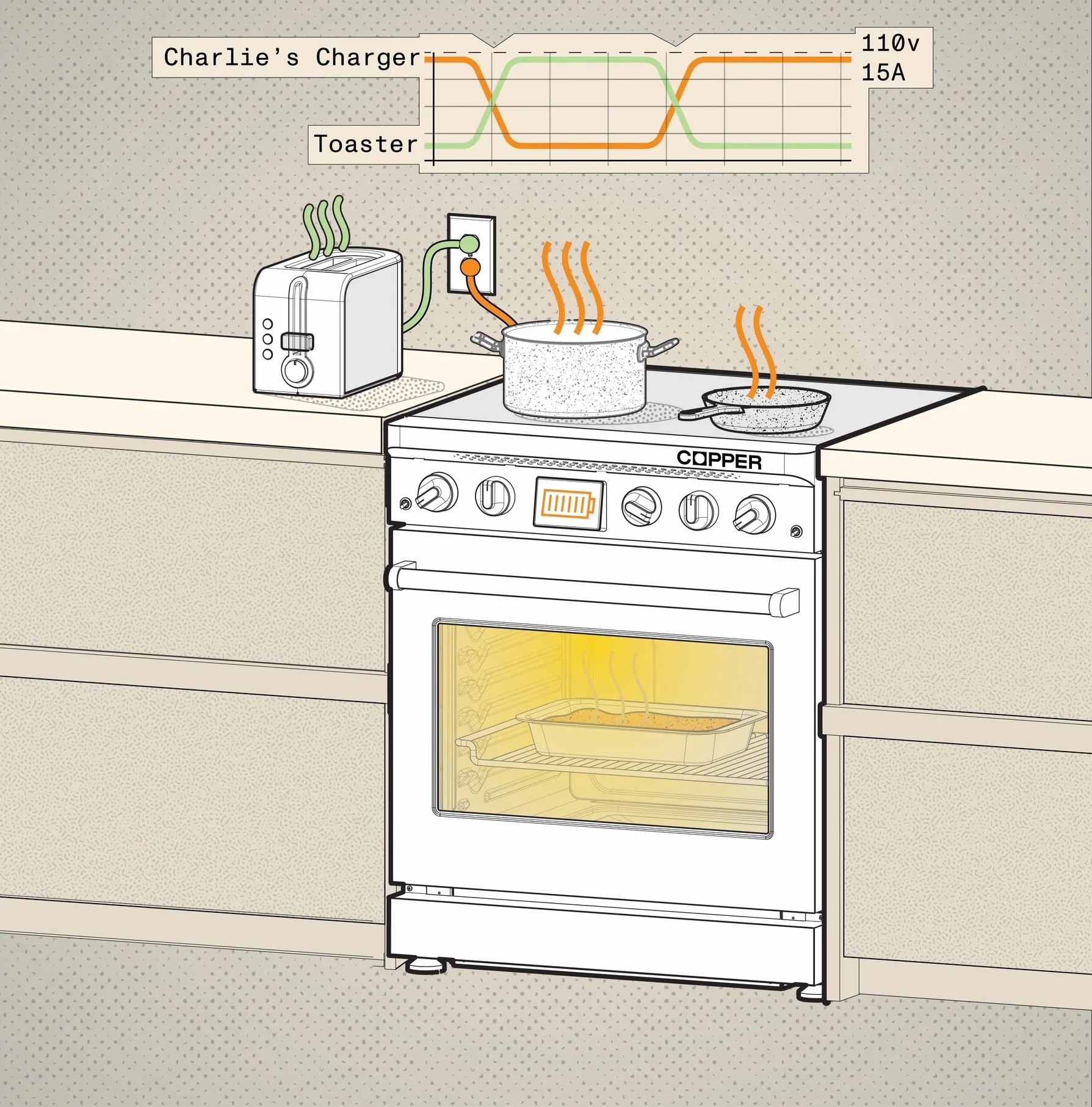

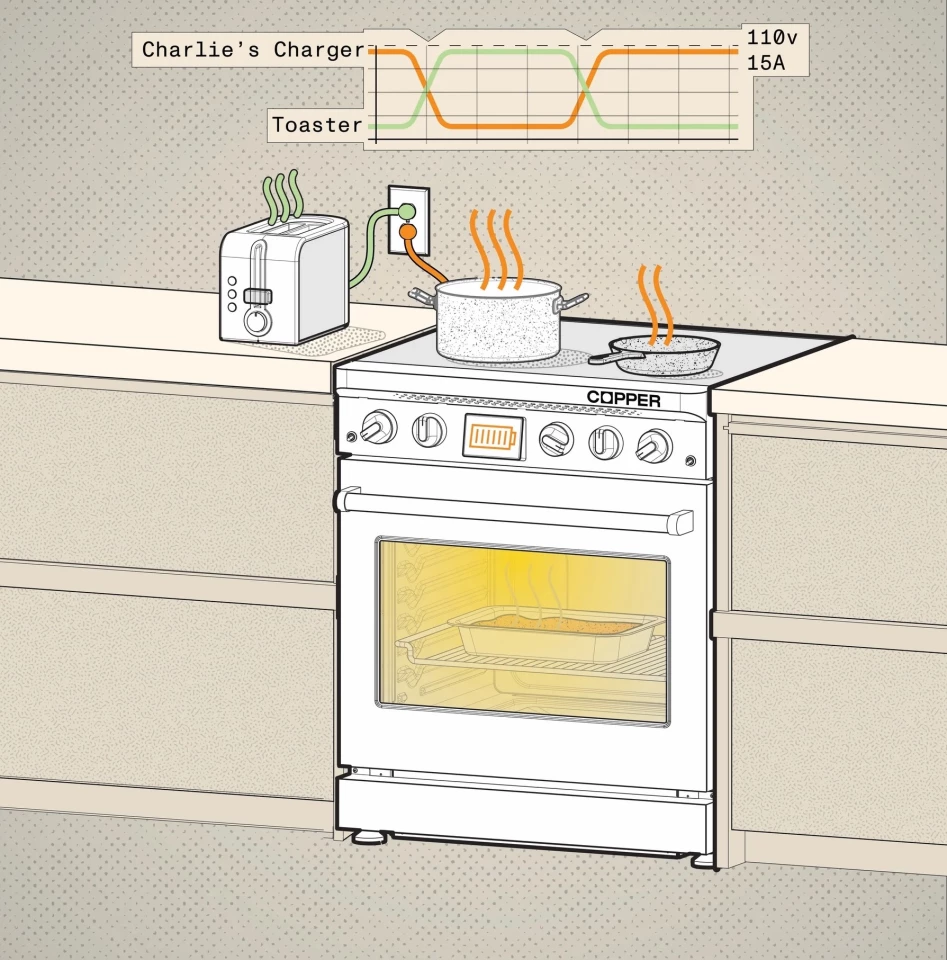

The stove’s charger draws less current than the 15 amps that would trigger a circuit breaker from a domestic socket. If you’re running a toaster or blender from the socket as well, it will reduce its demand automatically until you’re done with that task.

Peak output for the Charlie is 10 kW – with all burners and the oven flat-out – which would draw more than 80 A on a 120V circuit. The battery’s stored energy makes up the difference between demand and supply.

The founders of Copper had greenhouse gas reduction at the top of their minds when they set up the company and saw their stove as a way to help shift energy consumption away from fossil fuels. But they wanted householders to see functional benefits.

"From the marketing perspective, the question is how do we make this a story of choice, not one of sacrifice," Chief Marketing Officer Weldon Kennedy explained last year in an interview.

On the cooktop, the Charlie uses four 8-in (200-mm) elements, each with a maximum output of 2.8 kW. That’s about the same as a gas range’s big burner, except that more of the energy goes into the cookware and less into the air and stove surface.

An induction element comprises a metal wire coil, usually copper, that generates an electromagnetic field. The cookware produces eddy currents in response to the field, and these heat it. Pans with iron or steel in their bases work best; induction heating is ineffective with all-aluminum utensils.

The New York Times tried out an early production Charlie in January. "In my testing, it was immediately clear that the Charlie has functionality equivalent to that of all the induction cooktops and ranges we’ve previously tested," its reviewer concluded.

The Charlie’s battery should last 20 years, Copper says. It estimates that its stove could cook at least three meals for a family of four during a power outage.

And it says the battery’s high output allows the oven to preheat about four times faster than a typical gas oven.

So what’s the downside?

Weight, for one. A Charlie weighs 354 lb (160 kg), roughly twice what a typical mains-driven induction stove weighs. That’s a lot of mass for an installer to get up a long flight of stairs.

Price, for another. When you purchase a Charlie, you purchase not only the stove but also the battery, and high-performance batteries remain costly.

And you’d be relying for maintenance on a very new company, founded only three years ago.

While Copper has made a start with its stove, it has its eye on integrating battery power with other household appliances – hot water units, for example.

Would I have a Charlie? Yes, if it were available outside the US and the price had come down from its present level of US$6,000. I’ve recently signed off on a rebuild for my kitchen, but I’m sticking with gas to avoid the expensive, difficult rewiring process that would be necessary for installing an induction range in my home.

Source: Copper.