For some time now, we've seen robotic surgical devices that can be remotely guided within the human body. And while they do make surgery more precise and less invasive, they still have to be continuously operated by a surgeon. Recently, however, a robotic catheter successfully navigated beating pig hearts on its own.

The device was developed by a team at the Harvard-affiliated Boston Children's Hospital, led by chief of Pediatric Cardiac Bioengineering, Dr. Pierre Dupont. At the front end of the long, slender tool is an optical touch sensor – this incorporates an LED spotlight and an endoscopic camera.

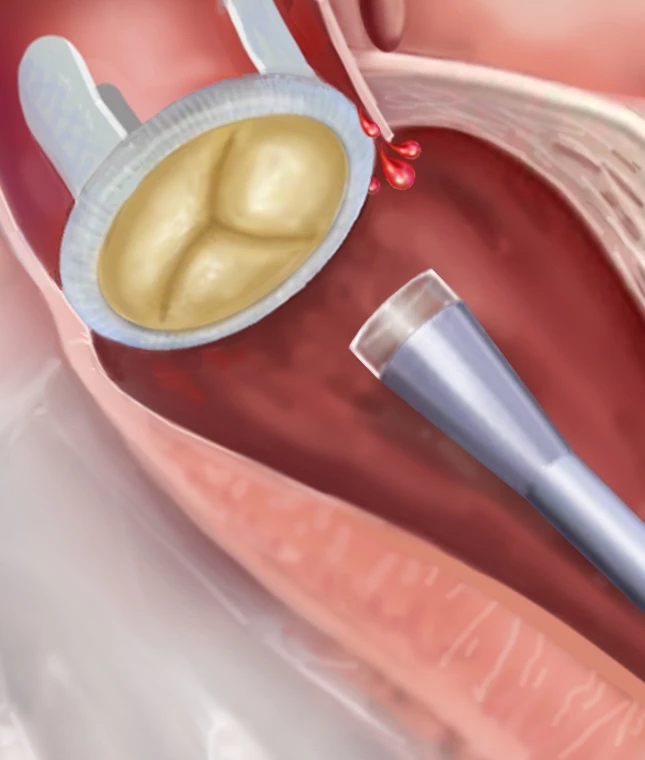

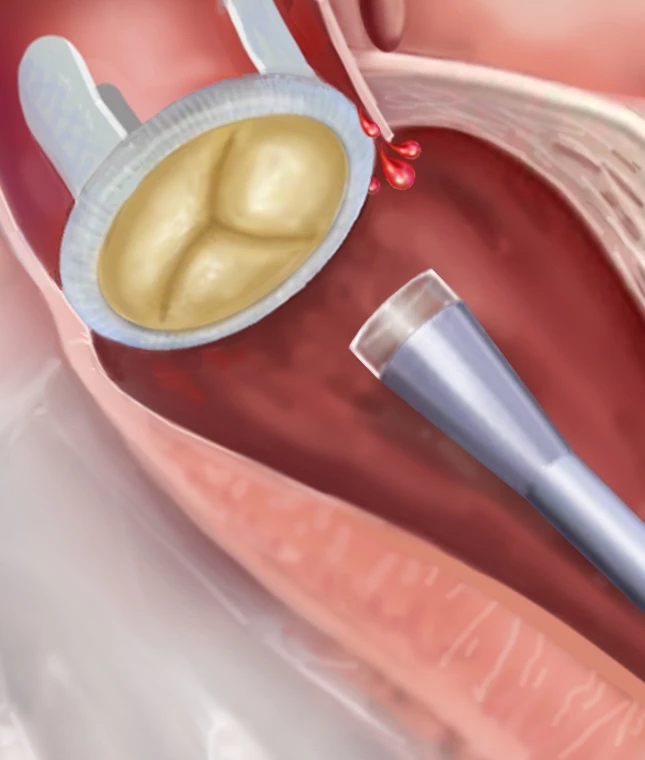

As an external motor pushed the catheter forward along the inner wall of the heart's left ventricle, images from its camera were processed by an artificial intelligence-based control system. That system was in turn able to determine if the sensor was in contact with blood, the heart wall, or a heart valve. Additionally, by visually assessing how much pressure the sensor was exerting on the surrounding tissue, the system was able to keep it from pressing hard enough to cause damage.

Based on a map of cardiac anatomy and preoperative scans of the individual pigs' hearts, the control system proceeded to ascertain where the device was within the organ, and how it needed to proceed in order to reach its target. That target was an artificial valve in the aorta, that had a leak which needed to be fixed. Once the catheter reached that valve, a surgeon took over, remotely operating a surgical tool on the end of catheter in order to plug the leak.

In trials conducted so far, the robotic catheter has taken slightly longer to reach the valves than a manually joystick-controlled device. That should change as the technology is developed further, however.

Ultimately, it is hoped that the system could free surgeons up to focus on the aspects of procedures that are most important. Additionally, it's possible that multiple systems operating worldwide could pool their knowledge online, sharing what they've learned to boost all of their performance.

"This would not only level the playing field, it would raise it," says Dupont. "Every clinician in the world would be operating at a level of skill and experience equivalent to the best in their field. This has always been the promise of medical robots. Autonomy may be what gets us there."

A paper on the research was recently published in the journal Science Robotics.

Source: Boston Children's Hospital via EurekAlert

For some time now, we've seen robotic surgical devices that can be remotely guided within the human body. And while they do make surgery more precise and less invasive, they still have to be continuously operated by a surgeon. Recently, however, a robotic catheter successfully navigated beating pig hearts on its own.

The device was developed by a team at the Harvard-affiliated Boston Children's Hospital, led by chief of Pediatric Cardiac Bioengineering, Dr. Pierre Dupont. At the front end of the long, slender tool is an optical touch sensor – this incorporates an LED spotlight and an endoscopic camera.

As an external motor pushed the catheter forward along the inner wall of the heart's left ventricle, images from its camera were processed by an artificial intelligence-based control system. That system was in turn able to determine if the sensor was in contact with blood, the heart wall, or a heart valve. Additionally, by visually assessing how much pressure the sensor was exerting on the surrounding tissue, the system was able to keep it from pressing hard enough to cause damage.

Based on a map of cardiac anatomy and preoperative scans of the individual pigs' hearts, the control system proceeded to ascertain where the device was within the organ, and how it needed to proceed in order to reach its target. That target was an artificial valve in the aorta, that had a leak which needed to be fixed. Once the catheter reached that valve, a surgeon took over, remotely operating a surgical tool on the end of catheter in order to plug the leak.

In trials conducted so far, the robotic catheter has taken slightly longer to reach the valves than a manually joystick-controlled device. That should change as the technology is developed further, however.

Ultimately, it is hoped that the system could free surgeons up to focus on the aspects of procedures that are most important. Additionally, it's possible that multiple systems operating worldwide could pool their knowledge online, sharing what they've learned to boost all of their performance.

"This would not only level the playing field, it would raise it," says Dupont. "Every clinician in the world would be operating at a level of skill and experience equivalent to the best in their field. This has always been the promise of medical robots. Autonomy may be what gets us there."

A paper on the research was recently published in the journal Science Robotics.

Source: Boston Children's Hospital via EurekAlert