Plastics are useful and ubiquitous – but that's not always a good combination. The vast majority of plastic waste can't be recycled, meaning it ends up in landfills at best or the ocean at worst. To help curb the problem, researchers at Berkeley Lab have now designed a new type of plastic that can apparently be reduced right back to its molecular parts, before being remade over and over.

According to the United Nations, about 300 million tonnes of plastic waste is produced every year. It's not surprising then that this garbage has found its way to the deepest parts of the oceans, is moving up the food chain and may even leave an indelible imprint on the Earth's geological record.

With awareness of the issue increasing, we're seeing bans on single-use plastics, huge ocean cleanup projects setting sail, and creative uses for recovered plastic waste, such as turning them into things as varied as bike paths, shoes, art installations and diesel fuel.

Even with all those options on the table, the majority of plastic waste ends up in landfills or incinerators, and that's largely because plastic is a tricky material to recycle. The problem is that different types of plastics – whether they're hard or soft, brightly colored or clear – are usually recycled together. That means they all get mashed up into one new substance with some relatively unpredictable properties.

So rather than design a plastic based on its life in use, the Berkeley Lab team focused on its afterlife. The new creation, named poly(diketoenamine) or PDK, can be reduced back to its constituent molecular parts and then reassembled as needed.

"Most plastics were never made to be recycled," says Peter Christensen, lead author of the study. "But we have discovered a new way to assemble plastics that takes recycling into consideration from a molecular perspective."

The most basic building blocks of plastics are molecules called monomers, which are tightly bound together into polymers and mixed with other chemical additives. Normally those bonds are hard to break, but the monomers in PDK plastic are designed to come apart more easily, allowing them to later be rebuilt into something new.

"With PDKs, the immutable bonds of conventional plastics are replaced with reversible bonds that allow the plastic to be recycled more effectively," says Brett Helms, lead researcher on the study.

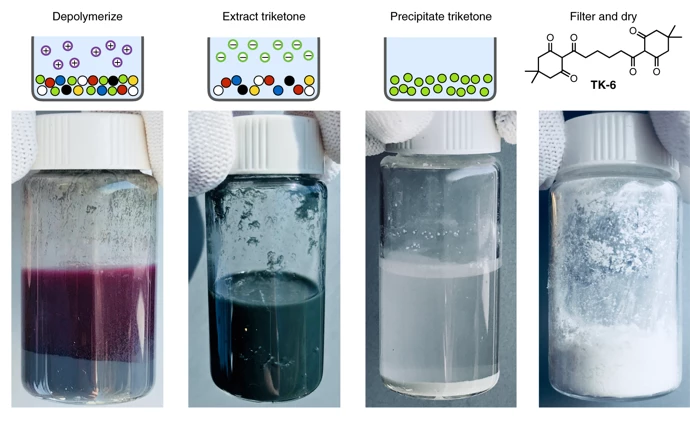

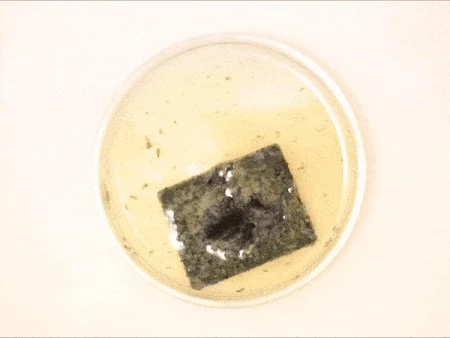

To do so, an old piece of PDK plastic can be dunked into acid. That degrades those bonds and reduces the material back to its original monomers, as well as separating them from other chemical additives. These monomers can then be reused in new plastic products.

The team tested various mixtures of the material, and then demonstrated that the whole cycle can work as hoped. The PDK plastics were effectively broken down in acid, and the resulting monomers were then rebuilt into new plastics. The colors and other properties of the old products didn't affect the new ones. The team says the plastics could also be "upcycled" into higher quality products by adding new chemicals.

Acid isn't the only way to break it down though. Other recyclable plastics can apparently revert back to their monomer state using heat, or other chemical catalysts.

The ultimate goal of PDKs and other recyclable plastics is to make the plastic industry more "circular," instead of linear that leads to the sea. But of course, that would require some pretty large infrastructure changes, including new collection programs and specialized facilities.

"We're at a critical point where we need to think about the infrastructure needed to modernize recycling facilities for future waste sorting and processing," says Helms. "If these facilities were designed to recycle or upcycle PDK and related plastics, then we would be able to more effectively divert plastic from landfills and the oceans. This is an exciting time to start thinking about how to design both materials and recycling facilities to enable circular plastics."

The research was published in the journal Nature Chemistry.