Scientists have found a massive area the size of 1.5 football fields, now dubbed "The Coliseum," which was once a popular thoroughfare to water for multiple species of prehistoric beasts over many generations some 70 million years ago.

While we can’t confirm if the arrangement of footprints suggested dinosaurs gathered here for gladiatorial fights like the Romans did at the rocky structure that inspired this site's name, the dinosaur Coliseum is almost as impressive.

Researchers at the University of Alaska Fairbanks made the discovery following a seven-hour hike into the Denali National Park and Preserve, and it is now the home of the largest known single dinosaur track site in the US state.

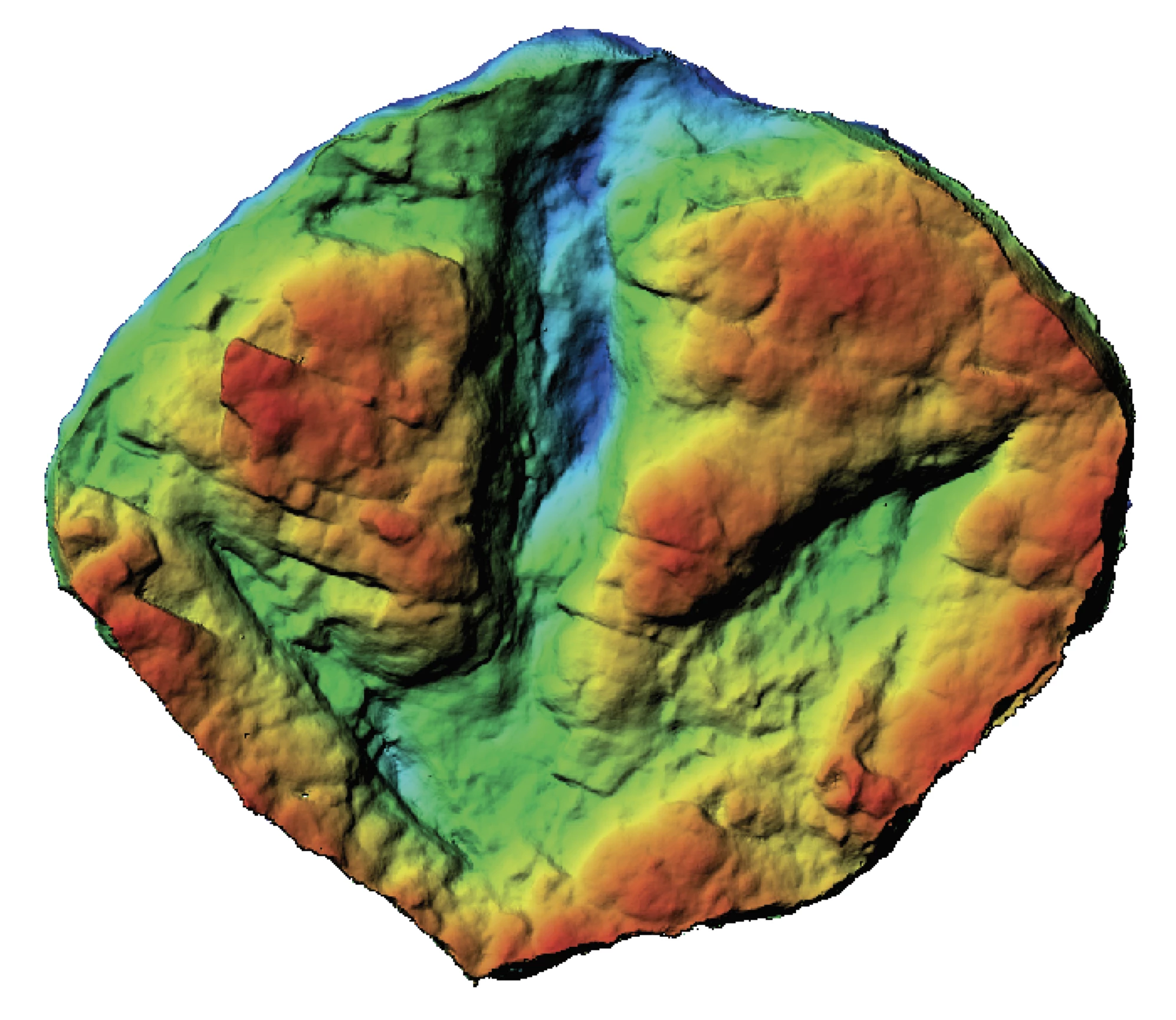

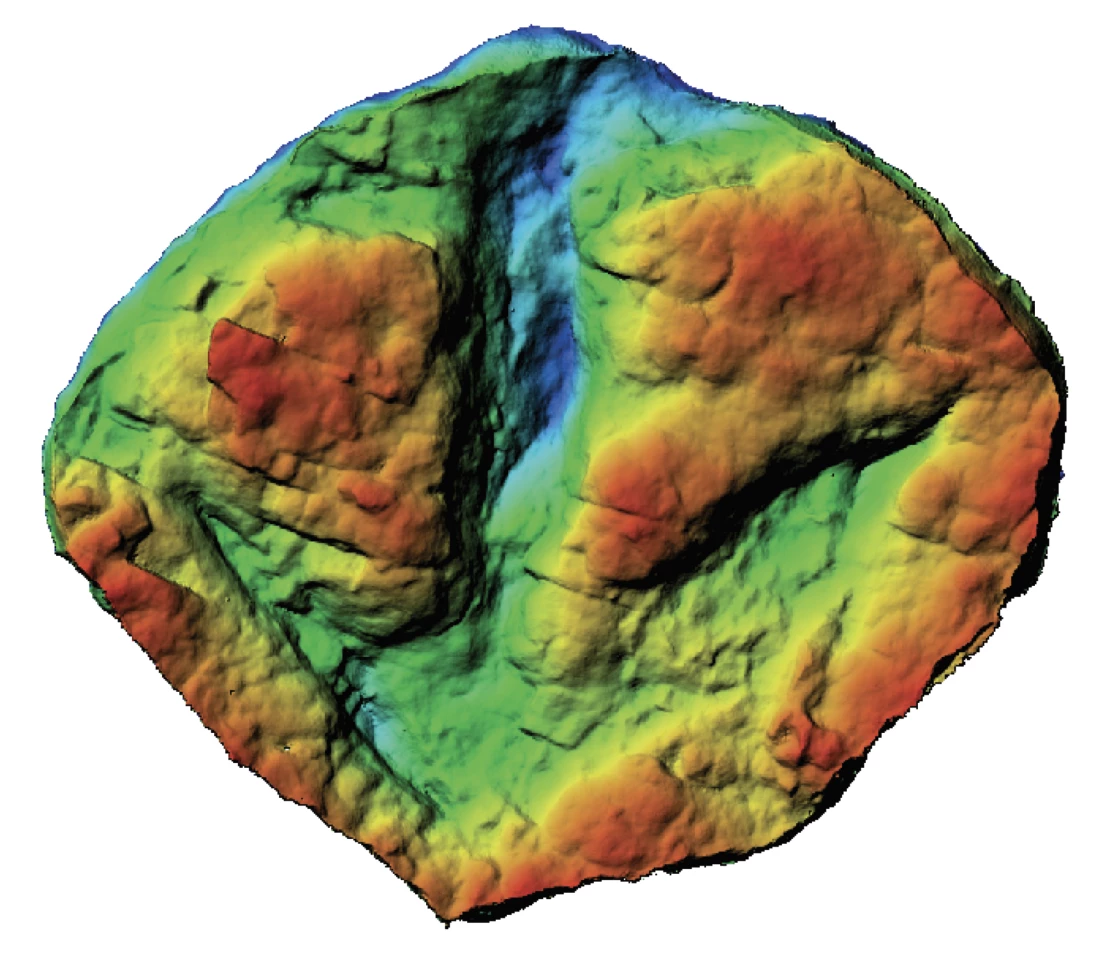

Like a geological triple-decker (or more) sandwich, the 20-story-high structure, pushed vertical due to tectonic plate convergence, reveals a cliff face of layer upon layer of preserved prints throughout time.

“It’s not just one level of rock with tracks on it,” said Dustin Stewart, the paper’s lead author and a former UAF graduate student. “It is a sequence through time. Up until now, Denali had other track sites that are known, but nothing of this magnitude.”

What’s more, it has been easily missed, with the prints hiding in plain sight depending on the light hitting the rocks.

“When our colleagues first visited the site, they saw a dinosaur trackway at the base of this massive cliff,” said Pat Druckenmiller, senior author of the paper and director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North. “When we first went out there, we didn’t see much either.”

However, as dusk approached, the fading sun hit the ‘dimples’ of the prints to highlight them, and the site revealed itself to the researchers.

“They are beautiful,” Druckenmiller said. “You can see the shape of the toes and the texture of the skin.”

In the Late Cretaceous Period, the cliffs were sediment on flat ground located by a likely watering hole. Tectonic plate activity pushed the ground upwards, folding it and tilting it, causing it to create a wall of tracks.

As such, the tracks are both original hardened impressions of footprints in the mud, and casts of tracks due to where sediment had filled in the tracks and hardened.

As for the species, juveniles and adults that frequented the site over thousands of years included large plant-eating, duck-billed and horned dinosaurs, as well as some carnivores, including raptors and tyrannosaurs, and small wading birds.

“It was forested and it was teeming with dinosaurs,” Druckenmiller said. “There was a tyrannosaur running around Denali that was many times the size of the biggest brown bear there today. There were raptors. There were flying reptiles. There were birds. It was an amazing ecosystem.”

The team also found fossilized plants, pollen grains and clues suggesting freshwater shellfish and other invertebrates.

“All these little clues put together what the environment looked like as a whole,” Stewart said.

The area, popular with visitors for its natural beauty today, would have been just as stunning 70 million years ago, researchers say, though a little warmer, more akin to the Pacific Northwest.

“It’s amazing to know that around 70 million years ago, Denali was equally impressive for its flora and fauna,” Druckenmiller said.

The research was published in the journal Historical Biology.

Source: University of Alaska Fairbanks