They’ve been crawling across the seafloor for more than 500 million years – predating the dinosaurs – yet sea stars remain some of the most misunderstood animals on Earth – if they’re even recognized as animals at all. Now, a new discovery about their spine-speaking communication has lifted the lid on these alien-like marine predators, and could help us finally gain the advantage in this ecological arm's race.

A team of researchers from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), Australia's University of the Sunshine Coast and the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) in Japan has discovered that one such sea star – the infamous crown of thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) – uses its spiky body armor to "smell" chemical messages sent out by others. The invisible communication network acts like a kind of marine mind control, allowing the brain-less, blood-less animals to stay connected and move and act together.

While they may look like inactive marine wallflowers, crown-of-thorns starfish (CoTS) are incredibly destructive predators, able to amass as a swarm and devour acres of coral in a few months. And this newly discovered communication channel between individuals may be driving these mass gatherings and reef killings.

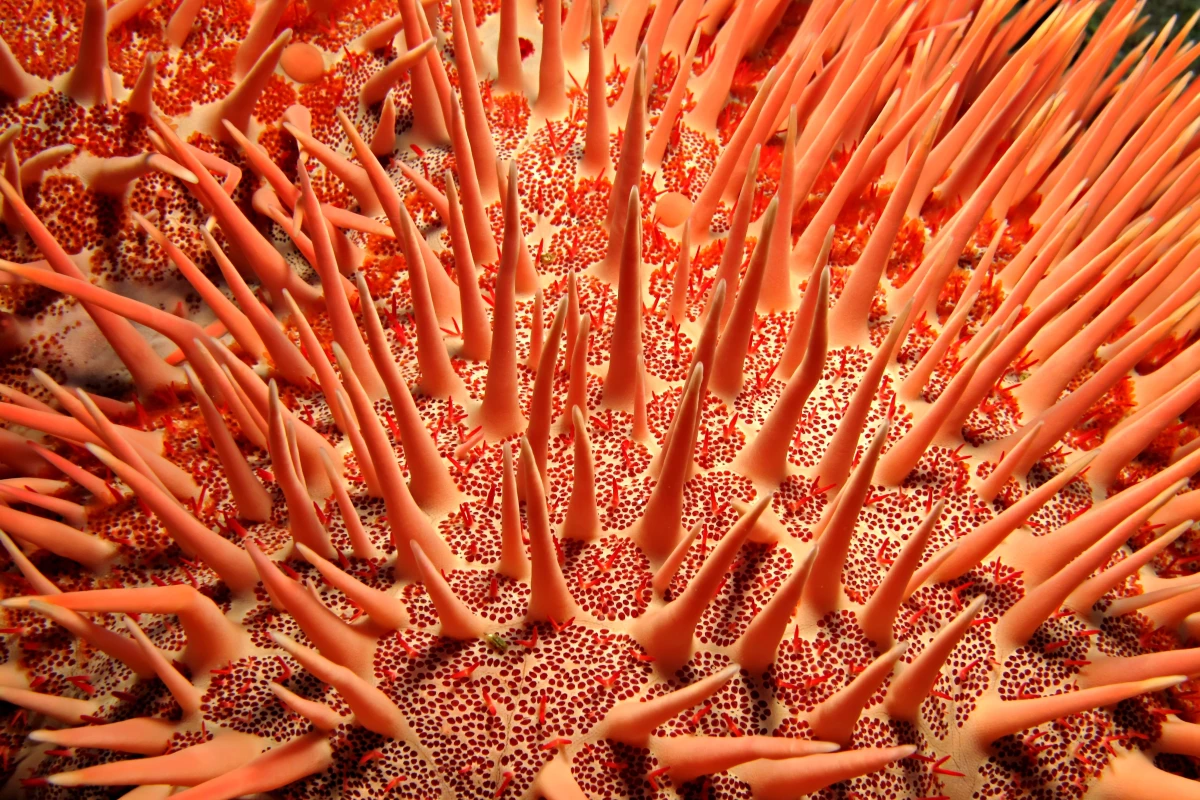

The scientists found that the sea stars don't crowd together by accident, but they're actively passing biochemical notes to each other, sent out and received by their long spines that cover their flat bodies. When the team extracted certain proteins – deemed crown-of-thorns starfish-secreted proteins (COTSP) – from these spines and introduced them to the water of animals held in tanks, the sea stars became more active and moved in certain directions. External stressors were ruled out as being an influence on this behavior.

The researchers recognized that the patterns of movement were triggered by the COTSP, traveling through water like aquatic smoke signals. The proteins were not part of any known immune or stress response, nor were they a result of any other physical action like skin shedding. As to what messages they carried, that's something that remains a mystery. Through gene expression studies, the team determined these proteins were actively produced and regulated – social control molecules secreted through their natural antennae, the spines.

This discovery is a big deal – until now, efforts to control outbreaks, or swarms, of these animals have been laborious and largely futile, requiring individual animals to be sited and removed. Sea stars, in general – like Australia's invasive Northern Pacific sea star (Asterias amurensis) – can lose limbs or even much of their body in an attack and regrow the tissue, as long as their central disc that houses their stomach remains intact. And while CoTS are invertebrates, their exposed topside is tough, and covered in long, sharp venomous spines that cover this disc and their many limbs.

They're also deceptively muscular and agile, sliding over and wrapping themselves around sessile coral, liquefying their pray with digestive enzymes to suck directly into their stomachs.

We've known for some time that swarms of CoTS are bizarrely synchronized, but just how they were staging these coordinated attacks has remained a mystery. Now, this new insight into their collective messaging and behavior could help scientists hijack their communication channels and lure them to a central location for culling.

Building on their discovery, the scientists created a non-toxic, low-dose synthetic peptide that could consistently attract other CoTS. This concoction, known as Acanthaster attractins, triggered the animals to gather in one place. And it could be a significant advancement in the battle to save Pacific Ocean reefs from these voracious predators.

“Through genomic and proteomic analysis, we found that the CoTS spines are used to both sense and secrete a wide range of peptides – not just defensive toxins,” said Professor Noriyuki Satoh, head of the Marine Genomics Unit at OIST. “So we synthesized the peptides that we suspected function like pheromones for communication and found that they consistently affect the trajectories of the starfish. With these attractins, we hope to contribute to the development of an efficient and safe measure against CoTS outbreaks.”

The study was published in the journal iScience.