In a breakthrough study, scientists have transferred a courtship behavior from one species to another, triggering the recipient to perform this completely foreign act as if it was its own. While genes have been swapped between species to influence traits, a totally unknown behavior has never been genetically swapped into a different animal before.

Nagoya University researchers achieved this remarkable feat by manipulating a single gene to create new neural connections and transfer behavior between two distinct fruit flies, Drosophila subobscura and D. melanogaster. While both species belong to the family Drosophilidae, they have distinct neural circuits that drive very different mating behaviors.

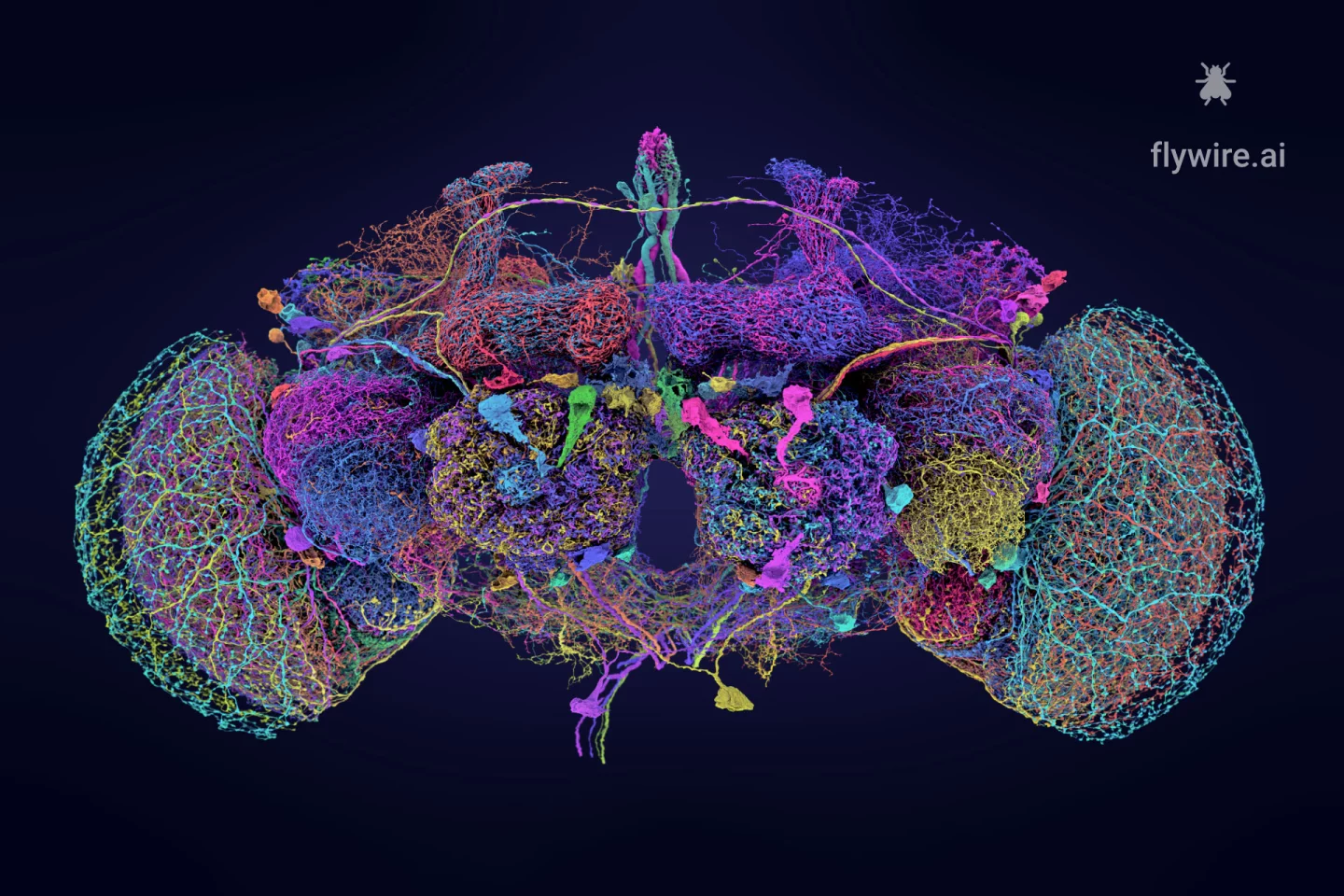

It’s the culmination of nearly a decade’s work by several members of the Japanese team, including co-first author Ryoya Tanaka, who in 2017 led a study mapping and comparing the mating circuits of the two fly species – D. melanogaster, which courts by singing, and D. subobscura, which regurgitates food as a romantic gesture ("gift-giving"). By using optogenetics to trigger gift-giving in D. subobscura, they confirmed that a gene called Fruitless (Fru) – present in both species – played a key role in courtship, but controled very different behaviors in each.

Now, the Japanese researchers have taken this to a completely new level, using genetic manipulation to turn D. melanogaster males – who diverged from the other species around 35 million years ago – into gift givers, not singers. While we can't say for sure, when the increasingly distinct species continued down their own path of evolution from a common ancestor, environmental pressures and mating preferences would have shaped their "love language." One refined its wing muscles and song circuits to produce the sonic courtship ritual, the other boosting the visual and motor circuits for regurgitating and presenting food to a female.

Essentially, turning D. melanogaster flies into gift-givers is not something that can be "unlocked" – it vanished possibly tens of millions of years ago.

Scientists have now upended this evolutionary journey, genetically rewiring the brains of D. melanogaster by "switching" on the Fru gene in the singing flies' insulin-producing neurons – where you'll find the gene lurking in the heads of the gift-givers – to manipulate it to form totally new neural connections, resulting in the behavior transferral to the other species.

It represents the first example of manipulating a single gene to transfer this foreign behavior to another species.

The scientists inserted DNA into D. subobscura embryos so that certain brain cells would produce heat-activated proteins. By briefly warming the flies, they could switch these targeted neurons on. This revealed a cluster of 16–18 insulin-producing neurons in the pars intercerebralis – the insect brain’s neurosecretory center – that make the male-specific protein FruM. Comparing this region to D. melanogaster showed that, in the gift-giving species, the insulin neurons are wired into the courtship circuit – while in the singing species, they're not.

In D. melanogaster, the insulin-producing neurons aren’t connected to the Fru-driven courtship circuit, which means regurgitation simply isn’t part of their skillset – their wiring and genetic programming make it impossible. However, the researchers figured out how to switch on the fru gene in these neurons, effectively rewiring the circuit so the singing flies could perform the foreign gift-giving behavior.

Remarkably, this behavioral switch occurred with no learning or social exposure – it came about purely through reconfigured neural circuitry.

“When we activated the fru gene in insulin-producing neurons of singing flies to produce FruM proteins, the cells grew long neural projections and connected to the courtship center in the brain, creating new brain circuits that produce gift-giving behavior in D. melanogaster for the first time,” said Ryoya Tanaka, co-lead author and lecturer at Nagoya University’s Graduate School of Science.

The genetically engineered courtship transfer highlights how some animals may carry hidden, evolutionarily dormant behaviors in their neural architecture. So activating the right genetic switch can awaken these ancient programs – even if they’re completely foreign to the species in question.

“Our findings indicate that the evolution of novel behaviors does not necessarily require the emergence of new neurons; instead, small-scale genetic rewiring in a few preexisting neurons can lead to behavioral diversification and, ultimately, contribute to species differentiation,” said co-lead author Yusuke Hara, from the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT).

But this is more than a mad-science experiment – fruit fly species, although distinct from each other, share around 60% of their genetic makeup with humans. And scientists believe three in four human genetic diseases have a parallel condition in fruit flies. It's no surprise that research on fruit flies – the model species D. melanogaster, in particular – has earned scientists six Nobel prizes to date. In 2024, researchers created the most detailed neuronal map of the fly's brain.

This latest study offers real proof that small genetic tweaks – in this case, a single gene – in circuitry can redesign behavior at a species level. While no-one is suggesting we’ll be engineering new instincts in humans anytime soon, the work shows it’s possible to activate entirely novel behaviors by tweaking the brain’s wiring at the genetic level. It hints that some behaviors may lie dormant in our own biology – hard-wired but silent – waiting for the right molecular “switch” to turn them on.

"We’ve shown how we can trace complex behaviors like nuptial gift-giving back to their genetic roots to understand how evolution creates entirely new strategies that help species survive and reproduce," said senior author Daisuke Yamamoto from NICT.

The study was published in the journal Science.

Source: Nagoya University via EurekAlert!