A fungus that attacked other organisms 407 million years ago has been unearthed among a collection of fossils, making it the oldest of its kind to have ever been found. The new plant pathogen has also been named Potteromyces asteroxylicola, in honor of The Tale of Peter Rabbit author and amateur mycologist Beatrix Potter.

While having your name attached to an ancient predatory fungus might not seem like the most complimentary of moves, Potter’s devotion to the study and documenting of fungi has become far more recognized in recent years. Producing beautiful drawings of wild mushrooms and examining their structures under a microscope, Potter was forced to stay an amateur enthusiast, given that women were largely shut out of professional sciences in the Victorian era.

It’s now accepted that Potter’s study of fungi growth was, at the time, decades ahead of research in the field. (Fortunately, she diversified her subject matter for her children’s books; The Tale of Peter Portobello doesn't quite have the same ring to it …)

"Naming this important species after Beatrix Potter seems a fitting tribute to her remarkable work and commitment to piecing together the secrets of fungi," said the study’s lead author Christine Strullu-Derrien, scientific associate at the UK's Natural History Museum.

But back to P. asteroxylicola. The fungus was found in fossil samples taken from the 407-million-year-old Rhynie chert sedimentary deposit, an important geological site near Aberdeen in Scotland that preserved incredible early Devonian life forms of plants, bacteria and fungi.

When Strullu-Derrien found the first P. asteroxylicola specimen in 2015, she noticed its reproductive structures, conidiophores, were unlike anything she’d seen before.

The specimen was found frozen in time, attacking an Asteroxylon mackiei plant. Now extinct, it remains one of the earliest examples of a plant with leaves in the fossil records. Upon closer inspection, the fungus wasn’t just attacking the plant, but the plant had developed dome-shape growths in response to it, suggesting it had still been alive when the fungus infected it.

But due to variability across individual fungus, a second specimen was needed. Lucky for researchers, they found one in a Rhynie chert collection housed at the National Museums of Scotland.

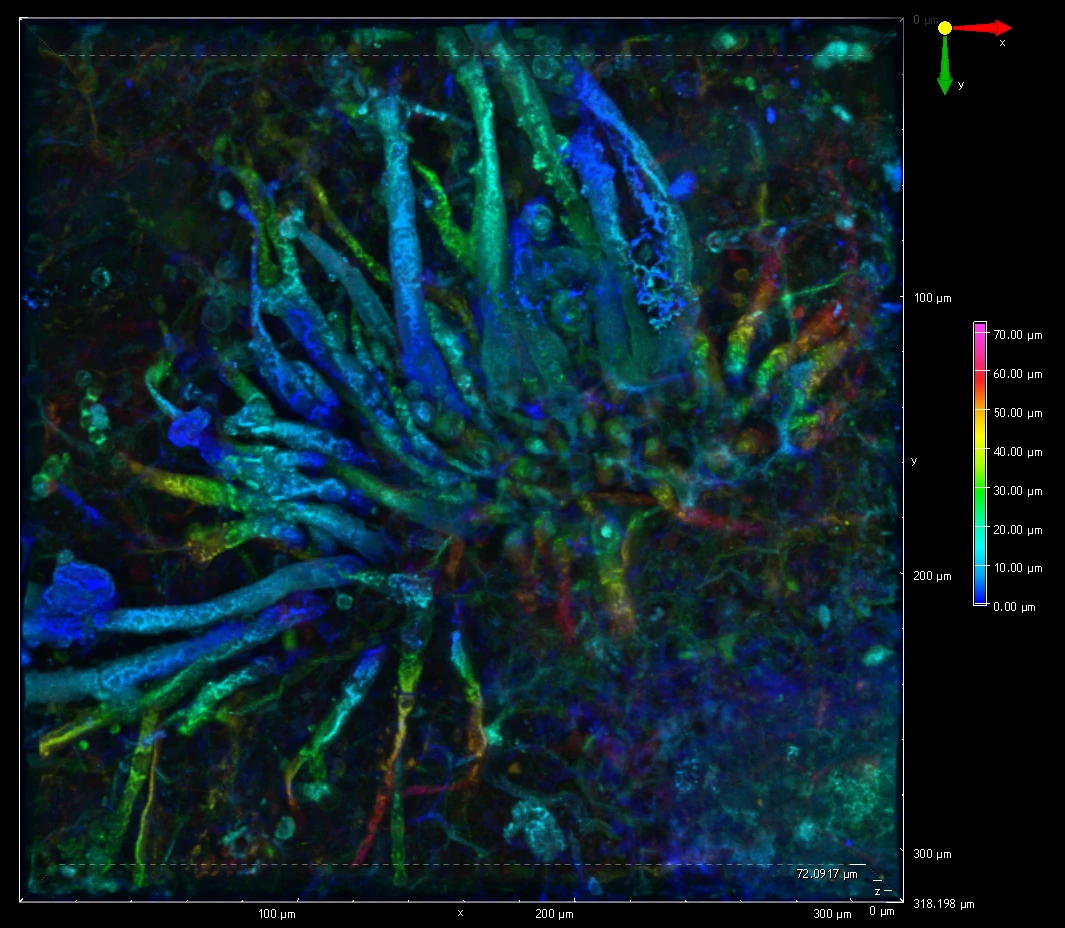

"New technology available to us, such as confocal microscopy, has enabled us to unlock more secrets from fossils housed in museum collections, such as those within the Natural History Museum," said Strullu-Derrien.

While technology and access to vast fossil collections have helped speed up discoveries in the field – something we imagine Potter would have been particularly excited by – Strullu-Derrien noted that these findings took 12 years to come about.

Still, this seems like a tiny blip on the timeline of this fungus, which was attacking plants some 407 million years ago. It’s a relevant finding, too, helping scientists trace evolutionary lines through to the present day.

"Although other fungal parasites have been found in this area before, this is the first case of one causing disease in a plant,” said Strullu-Derrien. “What's more, Potteromyces can provide a valuable point from which to date the evolution of different fungus groups, such as Ascomycota, the largest fungal phylum."

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Natural History Museum